Les Lofquist is not feeling too well. In the visitor’s center of the Mormon Temple Square, he stares at a projector screen lowered a few seconds before by an automatic timer. The Mormons’ latest public relations film has begun. Les shifts in his royal-blue padded seat, color coordinated with the slate-gray carpet. From linear-drive magnetic circuit woofers comes the soft voice of a man with extremely straight, white teeth. He is talking about the purpose of life.

The film, Les is forced to admit, is slick. It is spit-shined and glowing: the perfect husband, holding the perfect wife’s hand, while their perfect child holds a perfect rose while floating in a rowboat on a perfect lake on a perfect morning.

That explains some of his queasiness. But there is a more disturbing fact. Lofquist has been reminded, once again, that the odds are stacked against his ministry.

Les Lofquist, as is his custom on Sundays, is preaching. His church is a converted day-care center. More precisely, when the cardboard sign is hung on Saturday night, the Love-N-Care preschool day-care center becomes the Roy Bible Church. There’s not much to it, really. A “He Lives” poster covers some smiley-faced snowmen; sheer drapes behind the portable pine pulpit shut down the Disney Parade—Goofy and Mickey and Donald—into a sufficiently reverent white; a wooden cross hangs on one wall; and a hundred or so standard-issue, dirt-brown folding chairs are spaced across the carpet.

On this particular Sunday, Lofquist is preaching to about 70 people. “How many times have you been nervous about your puny little effort for Jesus?” he asks. From a far wall, Freddy the clown, green hair and red ribbons, smiles unimpressed.

With glasses on his baby face, Lofquist looks innocent or quizzical. He has precise, thinning blond hair, and a frame that whispers of an athletic past. He appears to be a man who tilts toward safe. He and his wife, Miriam, have four beautiful children.

But, on closer inspection, there is something unsettling, offbeat. Maybe a look in the eyes, the way a strand or two of hair doesn’t behave, a catch in the smile hinting at a hidden capacity for surprise and boldness.

Raised in the sixties, the son of an independent Minneapolis businessman, Lofquist grew up with the uneasy and strange combination of popularity and conscience. He was the captain of his basketball team and got high grades.

But, for some inexplicable reason, he began to tilt at windmills. Glory (and Lofquist has always, in some sense, striven for it) became equated with the magnitude of the odds. In high school, swept along by the sixties movement, he gave up basketball to take a shot at world hunger.

He organized two marches to raise money. Although he raised a good deal, he lost a good deal: “After the last march, I sat down in a telephone booth we had rented and cried great, heaving sighs. I guess I finally realized that I didn’t have resources to buck those kinds of odds. What was my one teeny voice crying in the wilderness?”

For the next few months, Lofquist drifted toward despair. Then he found Jesus. That revived his sense of hope. And his sense of daring.

Outside of Roy, Utah, there is a twirling tomato. “That’s the only thing I knew about Roy,” Lofquist says. “It was a sign for Sacco’s fruit stand on the highway. I said I would never go to Roy.”

Utah, for that matter, didn’t initially send chills up and down his spine. But, says Lofquist, “in college, all I knew was that I wanted to go to the mission field. And I knew that I wanted that mission field to be a hard one.”

While attending college, Les married. Miriam is the daughter of a missionary to Mormons in Utah. Les spent two summers in Utah and was exposed to the “overwhelming need.” (He also learned that Miriam’s father, during the first few years of his ministry, had to pump gas to feed his family.)

During college and seminary at Grace Schools in Winona Lake, Indiana, Lofquist continued to achieve. He was, in every sense, a man with a future. Popular, bright, handsome—an almost sure bet one day to have pencils that read The Fastest-growing Church in Lincoln County and, Possibly, the Surrounding World.

But his penchant for the long shot got the best of him. Through a combination of events, he became pastor of a church in Roy, Utah. The rising star went to the place with the twirling tomato. He had spent eight-and-a-half years training to be a pastor. At the time, there were eight people in the church.

Lofquist estimates there are about 1.7 million Mormons in Utah, which amounts to about 80 percent of the state’s population. The Mormons have nearly absolute control in matters dealing with legislation and the press.

Appeal and authority are two key factors in the Mormon empire, Lofquist says. The Mormons are good at creating images to attract potential converts. “Mormonism,” Lofquist says, “is an all-American religion. They play off positive values—family, patriotism, the work ethic.”

The authority operates on fear of ex-communication. According to Mormon doctrine, families married in the temple are together for eternity. A spouse who leaves the church, then, is separating a family for all eternity. And leaving the church in Utah means social ostracism, loss of prestige and social community, and possibly loss of job.

Christianity that relies on the Bible as its sole authority is practically nonexistent. Lofquist estimates that in the Salt Lake City area, there are probably 15 good churches. In his area—about 40 miles south of Salt Lake—there are two fundamental churches with a combined membership of about 300. The area has a population of about 250,000.

Behind the pulpit of the Love-N-Care preschool day-care center—make that the Roy Bible Church—Les Lofquist, bathed in Da-Glo yellow, is apologizing again. He admits he often feels like a comical voice in the wilderness: with Donald and Mickey and Goofy and the green-haired clown—another fool in a fool’s parade. “I don’t get overwhelmed so much as I get embarrassed,” Lofquist says. “I mean, we have such a great God and our people are such great people—and what do we have to show for it? A converted day-care center.”

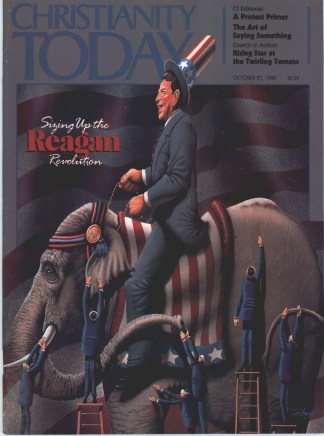

It doesn’t bother him so much, except when he picks up a Christian magazine, and some pastor is explaining the proper staff-to-laypeople ratio.

“There are standards that have been set up in the Christian community as to what success is,” Lofquist says. “A lot of that is based on numbers. You can’t measure success in Utah by numbers.”

He continues to talk, then there is a pause. It breaks the mood. Without question, there is something unexpected hidden behind the man’s smile.

By Rob Wilkins, a writer living in Winona Lake, Indiana.