The Salvation Army’s Kibera compound lies not 100 yards from the slum’s beer brewery. The odors of fermenting grain float overhead as Salvationist Captain Isaac Iballa and his wife Rose assemble a group of volunteers on a sunny Thursday morning. The volunteers are all members of the Anti-HIV/AIDS Self-Help Group. AIDS has brought death early and often into the lives of innumerable families in Kibera.

International health experts warn that the global AIDS epidemic is centered in eastern and southern Africa and that the 278 million people in 34 countries are at grave risk of infection and death. Since a majority of people in this region of Africa are Christian, health officials are cultivating new relationships with churches.

Public health officials are increasingly desperate to find effective ways of slowing new HIV infections. Health leaders openly recognize that the arrival of a safe and effective AIDS vaccine is in the distant future. Also, state-of-the-art AIDS drug therapy is rarely available for complicated political and economic reasons. Finally, the healthcare system in the region is one of the weakest worldwide and at times contributes to the spread of HIV due to inadequate blood screening and clinical hygiene. Health experts see churches and their community networks as unrivaled in their potential to fight AIDS through community awareness, care for the sick, and encouraging either sexual fidelity or abstinence.

Peter Kamau Chege is chairman of the Salvationist-sponsored self-help group in Kibera. He is among the few Kenyans with gray hair, because only 3 percent of Africans in the region live to 65 or older. Two years ago, Chege was one of the many heavy-drinking patrons who thronged Kibera’s bars. “I was like a man with my hand in the fire,” he once told his fellow volunteers, “and you helped me pull it out.” Since his commitment to Christianity, Chege has worked to motivate and mobilize Kibera’s Christians against AIDS.

“Since we don’t have a cure, we have to create awareness, to sensitize. When your neighbor is suffering, you are suffering,” he tells the volunteers. The self-help group has met weekly since 1995. Every volunteer is required to make a cash donation, a significant sacrifice in Kenya, where the average per-capita income is less than $6 per week. The donations purchase sugar or other staples that volunteers distribute freely when they fan out into Kibera to visit the sick.

Home visits form the centerpiece of the self-help group’s approach. As the volunteers end their meeting, they separate into teams. On this occasion, the teams are joined by several African Christian leaders who have come to study how to replicate the group’s successes. One team, after hiking through a hilly section of the Kibera slum, arrives at the one-room windowless dwelling of Bontiface Odhiambo. Rising from his cot, Odhiambo bears telltale signs of AIDS, including severe weight loss, but he does not openly acknowledge the nature of his illness. “I’ve been unable to travel home because I don’t have enough money,” Odhiambo tells Iballa and his team. He pays 1,000 Kenyan shillings a month for rent, which is more than many Kibera residents earn in a month. Volunteers sometimes discover that people with AIDS flee their families to hide in Kenya’s slums, eventually re turning home when they are days away from death.

After a few minutes, the team prays over Odhiambo, leaving a small store of sugar near his bedside. The visit clearly energizes Odhiambo as he shakes hands with each team member crowded into his closet-sized dwelling. The team zig-zags its way through many Kibera streets for the rest of the morning, visiting people known to be ill and uncovering new cases.

After returning to the Salvation Army compound, the teams discuss their field visits. Joshua Martin Bambo, a relatively new volunteer, opens up, telling the group of his harrowing journey from a career soldier to drug addict and finally selling his body for sex. As Bambo describes his turn to Christianity, he confesses for the first time that he is HIV positive, causing a stunned silence across the meeting room.

“When you visit it is a privilege,” Bambo says, nodding to his guests. “We have a model. If we can cut HIV, it is our pride. Take this message to others in Africa.” The silence within the group then dissolves into tears.

Then one of the visitors, Joyce Seitei of the Botswana Christian Council, tells the Kibera Salvationists: “In Botswana, the rate of infection is quickest of any worldwide. Our fear is being wiped off the face of the earth. I am challenged by seeing you do so much. You go out and do the work smiling. I’d do the same, but I don’t know how. You have been a lesson to me.”

Ian Campbell, a top Salvation Army officer, was also at the self-help group that day. As a physician and a leading expert in the church’s response to AIDS, Campbell observes dozens of community response efforts. He gives high praise to the Kibera teams, then offers simple advice: “Stay simple in your approach. Think strategically all the time. Trust in God.”

Counting Bodies

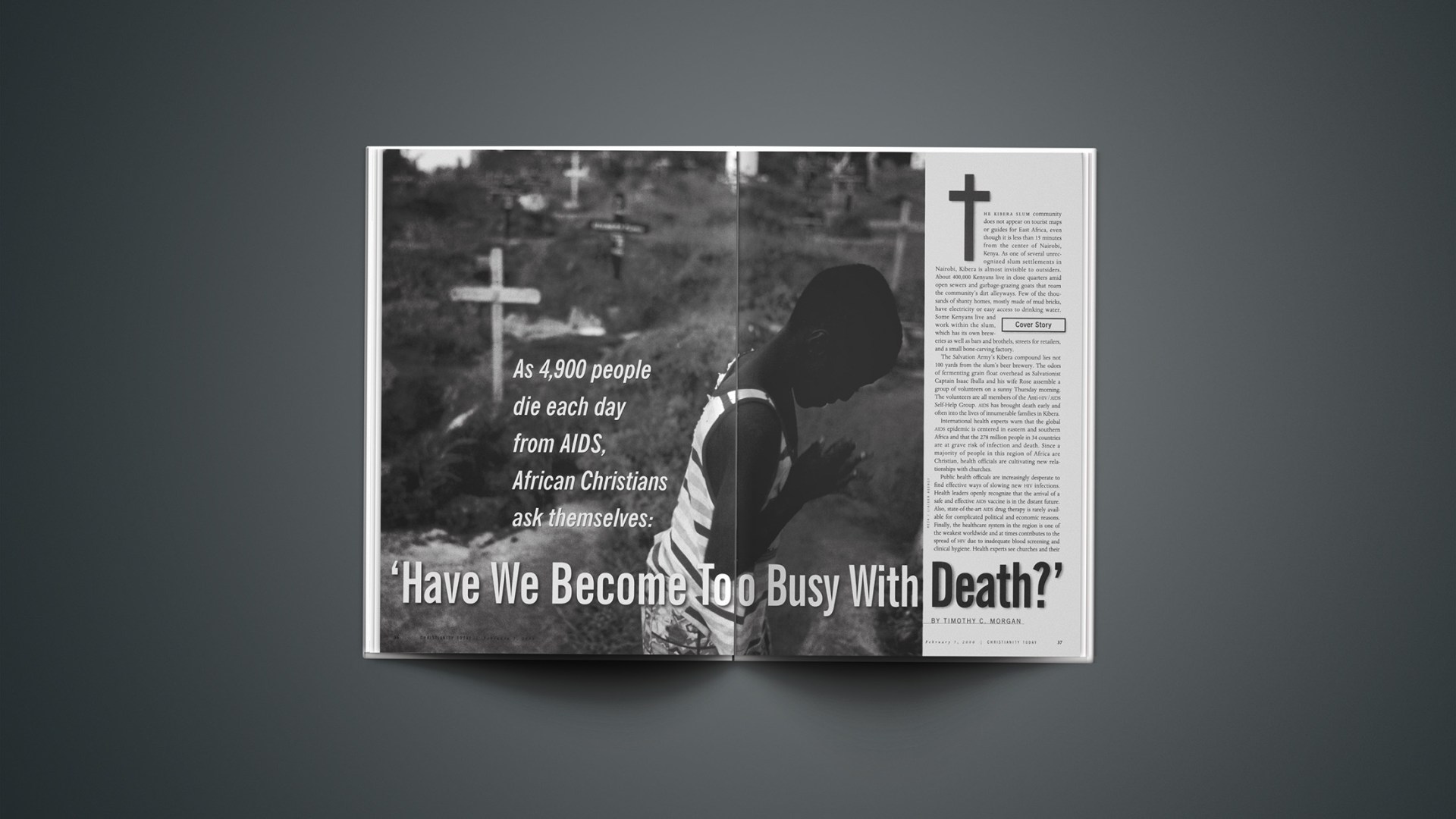

The visit of Campbell, Seitei, and others to Kibera was part of a unique initiative between the Salvation Army and the joint United Nations AIDS (UNAIDS) agency to stimulate Christian leaders toward aggressive action against the virus. After six international teams of Christian leaders visited AIDS ministry projects in eastern and southern Africa, they gathered in Gabarone, Botswana. Infection rates in some areas of Botswana approach 50 percent of the population, meaning that more than 150,000 Botswanans may die in coming years. Already, the life expectancy in Botswana (population 1.4 million) has plummeted to age 47.4. It was 65.2 in 1996.“You have come to Botswana at a time when we are counting bodies,” David Modiega, general secretary of the Botswana Christian Council, tells Catholic, Protesant and Orthodox leaders gathered in Botswana. “There is more pain and less joy. Lifestyles have changed to burying bodies. The questions that we are asking in churches now are: Are we giving time to worship? Have we become too busy with death?” For the next five days, 50 people at the consultation will sing and weep, praise God and confess to each other, and, in the end, recommit themselves against the epidemic.

Campbell says it is no longer possible to see the AIDS epidemic as being outside the church: “The church has HIV. We have HIV.” According to a church leader, one Salvation Army congregation in Kenya has lost about 60 members to AIDS.

Some AIDS experts question whether Christian teaching and practice have helped in the struggle against the disease.

A recent survey of mainline Christians in the KwaZulu-Natal region of South Africa found that their sexual practices, including extramarital and premarital sex, resembled those of non-Christians. The survey also found that Pentecostal Christians had the lowest level of extramarital and premarital sex, but Pentecostals are a tiny minority within South Africa.

The survey results suggest that the church’s influence is relatively insignificant. But that situation may change as more Christian leaders are self-critical, saying that denial, stigmatization, and censure have all compromised the church’s witness and ministry.

“I hope the church will move from being censorious to being based on the generosity of the Cross,” says Walter Makhulu, the Anglican Arch bishop of Central Africa. “Christians are denying the facts and misery of AIDS. The only approach is being self-righteous in condemning those who live with AIDS.”

Makhulu says that during a visit to Uganda, his team met with two women caring for 24 children orphaned by AIDS. “There is no humbug with AIDS. The consequences are clear,” Makhulu says. “We lost a brilliant young man [in the Anglican archdiocese]. He had just re-turned from Cambridge University with his Ph.D., and he was gone. We are losing skilled people.”

“The church has missed the opportunity to be a leader on AIDS,” says Dan Odallo, the UNAIDS official who works with churches in southern Africa. “In education and healthcare it was always the church. Government is always the latecomer.

“The church is uncomfortable with discussion of sexuality. The church has to play catch up,” Odallo tells the gathering of Christian leaders. “It needs to put its muscle and its resources into the battle. It’s important to get people to rethink the church’s role, not [to be] just a part of the death bed experience. Take leadership. Shake the governments.”

Bishop Paul, leader of the Coptic Orthodox Church for southern Africa, stands up after quietly listening to five days of brainstorming, testimonials, and debate. “I am changed,” he tells the group. “AIDS is a problem of my people. After this consultation, I will face the reality of my people. I have been too busy with administrative details. AIDS has been on the periphery. I confess that I saw AIDS as an eccentric issue. [It] won’t be a secret anymore. I’ll discuss it with children, and it must be shared at the family level.”

Families in Crisis

While Christian leaders focus on “care, compassion, and community,” they should not ignore the “chaos, confusion and corpses,” says Calle Almedal, a leading official with UNAIDS and the original spark for the Botswana consultation. Almedal, a soft-spoken Roman Catholic from Sweden, has been active in AIDS prevention since 1982.“This epidemic is going to change this continent more than anything else, more than colonialism, more than liberation,” he says. Much of that change will hit hardest at the family level. “The family can be a safe place, but also a dangerous place.” An infected man may transmit HIV to his wife, who then may give birth to infants carrying the virus. The experience of the Chaava household from Monze—a small village in Zambia about 74 miles from the capital, Lusaka—shows how one Christian family confronted AIDS but nevertheless lost seven of its members.

The Chaavas—parents Aaron and Rosah and their children Agness, Richard, Macdonald, Leonard, Alvin, Patricia, and Maynard—were active in the local Salvation Army congregation. Today, only three of the immediate family, several in-laws, and grandchildren survive. “The story of my sister is still as bright today as in 1988 when she died,” says Macdonald Chaava, a hemotologist at Chikinkata Salvation Army Hospital in Zambia.

Both parents were trained as teachers. Aaron worked in the local primary school and their family was healthy, prosperous, and happy. “My parents were very sincere Christians,” Macdonald remembers. But after Aaron Chaava was transferred to another school system, he began drinking and slipped away from his Christian faith.

Meanwhile, Macdonald Chaava completed his education, got married, and eventually joined the Salvation Army. He recalls becoming “so hot” for proclaiming the gospel that one day he assembled his family members and preached to them until they all reaffirmed their faith. “I was so bold, daring, and clear. I was completely unaware of the storm around the corner. After that family meeting, I was confirmed as the family priest.”

Macdonald’s older sister, Agness, worked in the Zambian copper belt as the secretary for a town mayor. Her husband died in an auto accident in 1971. After that, she had two children with other men. In 1984, she was diagnosed with tuberculosis and was unable to work.

At the end of 1987, Chaava received an urgent call from his parents: “Son, you have to come home!” He found his sister crying and in pain. She had her six-month-old son Imboela with her. “Here I am, supposed to know the mind of God and call down heaven,” he recalls. “We thought she had malaria. But that started our journey into the heart of darkness. When you have someone that sick, you don’t count the cost.

“Our neighbors advised us to go to tribal healers. ‘There is hope,’ they said. Until faith is personalized, we are helpless and swept away by our culture. And so it was with us. My father told me to take her to the witch doctor and I said, ‘This isn’t what the Bible says.’ He said, ‘The whole clan wants this to happen.'” Macdonald agreed only to transport her there.

Later, they attempted to get her into a hospital, but there was no room. Months afterward and near death again, she stayed at the witch doctor’s house for four days.

Early on July 31, 1988, Agness was admitted to a hospital ward. Nurses were unable to draw blood since she had lost so much body weight. That night, Macdonald and his father slept in an abandoned car outside the hospital. When they returned, their mother was there and his sister was gasping for breath. “Macdonald, I am very sorry” were her last words. “It’s OK,” Macdonald told her. “We are all coming that way.”

After Agness died, Macdonald put her body into the back of his car and returned to their village for the burial. “We had missed parts of her life,” he says. “I didn’t get the story until she was gone.”

Less than two years later, Macdonald’s father died of AIDS. In 1991, Macdonald’s mother died, probably of AIDS received from her husband. She was buried with Salvation Army honors and 500 people attended the funeral. “People knew about HIV, but it was hush-hush. That’s as far as the stigma went. People were thinking, ‘I wonder who is next?'”

As it turned out, more members of the Chaava family were next. Macdonald’s brother, Alvin, was diagnosed with HIV, yet got married anyway. His new wife conceived and miscarried. Then they had a baby girl, who died a week later. Alvin died three years after getting married.

“Alvin saw his death coming and he prepared himself until the day he died in December 1996,” Macdonald Chaava says. “I was home on holiday with family. I decided to go to the village to see my brother. But he had died that morning and they told me to get him in the mortuary.” Through much of the 1990s, Chaava says, his family was whipsawed between weddings and funerals. The last milestone was in 1997, when his sister Patricia died, leaving her husband and one child from another man.

In the aftermath, distant relatives began to play greater roles in the lives of the surviving Chaava family members. Caring for orphaned children brought new complications. Macdonald’s nephew Imboela was orphaned as an infant. The boy lived with his grandparents until they both died. Then Imboela lived with two uncles and one aunt, all of whom are now dead. At age 10, Imboela has known nothing but loss. For a time, Imboela lived with his stepfather.

But Macdonald Chaava says his tribe’s “culture moved in.” Two older cousins from the tribal family came to visit Imboela. “Our cousins took him out for a day and they never came back.” Both the cousins and Imboela have been missing for more than five months.

Macdonald Chaava is quick to express his family’s feelings of loss, but he is not so eager to draw conclusions about the family’s experience. He and his wife Tabisa, who also works for the Salvation Army, are pouring their lives into provoking church leaders into action against AIDS. Thebisa Chaava compares their work to hunting big game. “We are shooting a running animal. If we stop, we lose sight of the epidemic. We have to run.”

Five Million Deaths a Year?

The AIDS death toll worldwide through 1999 is 16.3 million, according to UNAIDS. In 1998, 2.5 million people died—the most AIDS deaths recorded in one year. (Statistics for 1999 are not available yet.) Other estimates for 1998 reveal that 4 million new HIV infections occurred in sub-Saharan Africa, bringing the total number of people with HIV or AIDS in the region to 22.5 million.Researchers offer dramatically different projections for AIDS deaths in Africa. The most optimistic picture projects 600,000 to 800,000 deaths per year, peaking in 2005. But U.S. government international health experts, using additional data, estimate up to 5 million annual deaths by 2015, rising to 5.7 million by 2020. Some African nations may lose 20 percent of their populations.

Researchers have found that several factors accelerate the spread of disease and death in Africa. Multi-drug-resistent tuberculosis (TB) continues as a key factor in taking African lives. Many TB deaths occur in conjunction with AIDS, since the virus severely weakens the immune system. Also, new field research in 1997–98 found that girls, ages 15 to 19, were HIV positive at rates of 15 to 23 percent. Men 25 and older had infection rates of 26 to 40 percent. But boys ages 15 to 19 were only 3 to 4 percent HIV positive.

Researchers conclude that older men have sexual relations with, and infect, younger women. A tribal tradition called “sexual cleansing” claims that a person can be healed of disease by having relations with a virgin. In addition, as more people learn about HIV transmission, promiscuous men seek younger women, who are less likely to carry the virus. Another traditional practice known as “wife inheritance” may also accelerate transmission of the virus. In some cultural traditions, when a husband dies, his estate, including wife and children, are inherited by another man in the immediate or extended family. If an HIV -carrying husband transmits the virus to his wife and later dies, his wife may unknowingly carry the virus into another family group.

But knowledge of how the virus spreads through Africa has rarely translated into programs that decrease the rate of infection. Uganda is the lone African nation with a significantly high AIDS rate to achieve a reduction in the rate of new infections. (CT, April 4, 1994, p. 70).

Odallo of UNAIDS identifies seven reasons why past approaches have often failed:

- The lack of national political commitment.

- A sole focus on the health sector.

- Exclusion of local community involvement.

- ; The short duration of intervention programs.

- Single interventions (such as condom distribution).

- Top-down efforts not tailored to grassroots needs.

- Overseas donor programs with competing agendas.

“Donors come in with their own agenda,” says Godfrey Rabanthews of Botswana Christian AIDS Intervention. “If the focus is on AIDS orphans, there is not sufficient attention paid to the family issues that created the orphan in the first place.”

Both Odallo and Almedal of UNAIDS concede that neither medical science nor government intervention has the full capacity to compel people to change their sexual behavior or to care for the millions of Africans with AIDS.

“We can do more. We can do better. We need to do it now,” Odallo says. “We need to reexamine how we do business and change government policy. Many governments do not even have a policy. Government needs to put its money where its mouth is. There is more zeal than skill and a low capacity for change.”

“To me, being a Christian has an imperative: You have to do something,” Almedal says, adding that the United Nations recognizes the role of civil societies, including churches. “We see no difference between the Red Cross and the church. If the church can deliver services, why not work with them?” Almedal says Christian leaders should set an achievable goal. He urges Christians to press political leaders to do three things: talk more openly about the AIDS epidemic; establish stronger partnerships with ministry groups, including churches; and provide better care for people with HIV and AIDS.

For their part, some African church leaders concede that they have not openly addressed the problem of sexual promiscuity within the church or effectively promoted sexual abstinence among young people. Church leaders recognize that the sexual habits of some Christians are no different than those of their non-Christian neighbors. Thus, the spread of HIV within many church communities has gone largely unchallenged.

Means to Mission

As a leader in the Zambian Pentecostal church, Joshua Banda is not satisfied in solely pastoring a growing congregation. Banda also commits himself to evangelistic crusades throughout his country of 11 million people, of whom about 46 percent are either Protestant or Roman Catholic.“AIDS is one of the freshest frontiers for mission in the twenty-first century harvest,” Banda says. “The gospel is a total package: deliverance, healing, and preparation of the soul for hope beyond the grave. The total package must include HIV-AIDS.

“It’s almost like the final frontier, a neglected frontier. In the north of Zambia, [Muslims] have to be addressed on the social front. I could go in with a team of experts, and through our presence evangelization will take place. I see HIV-AIDS as a point of entry, a door.” Banda says that when Christians provide health services to Muslims or others, it helps build new relationships, from which Bible studies may be started, which he hopes will eventually lead to new congregations.

One of the highest goals among AIDS ministry leaders is stimulating what they call a “naturally occurring response” from within a community. Such a response draws on local resources and responds to specific problems of people with AIDS.

In 1990, one congregation in Zambia faced a crisis of faith when a pastor and his wife became HIV positive, according to Jacinta Maingi, a regional coordinator for AIDS ministry in Kenya. “After the wife died the church panicked,” Maingi says. “They did not want a pastor with HIV. No one wanted to take communion from him.” A bishop transferred the pastor.

Maingi and a counseling team came in for training and workshops. “As long as you are not going to have sex with your pastor, you won’t get AIDS,” they told church members bluntly. The pastor eventually returned to the original congregation and later died. The congregation has since become a catalyst for change in AIDS education and pastoral training.

Similar community-based responses are emerging throughout sub-Saharan Africa. In Tanzania, the Kwetu Project focuses on commercial sex workers, mostly prostitutes, who have an extremely high rate of HIV infection. An ongoing debate among Christians is whether to endorse the use of condoms. For the Salvation Army’s Ian Campbell, it’s reasonable to distinguish between condom use for birth control, opposed by the Roman Catholic Church and other Christian groups, and condom use to check the spread of sexually transmitted diseases. The top goal for the Kwetu Project is to present viable alternatives to commercial sex workers, but also to educate them concerning AIDS prevention.

Research on HIV transmission has found that young people from ages 15 to 24 are at highest risk for getting the virus. UNAIDS research says that finding a source of income is the most pressing need of young people once they are out of school. In some cases, teenagers from rural regions migrate to African cities, where they may be quickly drawn into the sex trade. At the Sechaba Youth Agricultural Cooperative, supported by the Botswana Christian Council, young people are trained to manage in small-scale agriculture, mostly raising chickens and goats, which are sold on the open market in Botswana. Mpho Moruakgomo, a pastor from Gabarone, says the program is successful not only in keeping rural young people closer to their villages and families, but also provides an opportunity to teach them about AIDS. He acknowledges the work is demanding. “It’s difficult to get the kids to stick with the program. They are too impatient.”

The price of partnership

“If I had known in 1982 how difficult it would be, I wouldn’t have continued,” Almedal says of the battle against AIDS. “It’s going to be worse tomorrow than it is today.“We have more questions than answers: Is microbiotic life more intelligent than human beings? What is our highest value? Isn’t it to save life? AIDS eats up structures, not only families: doctors, teachers, journalists. It erodes the fiber of society. Church leaders are equally affected. We work with churches, but the church is not less touched.”

Ian Campbell believes pastors and ministry leaders should reform their efforts. “Caring by participatory relationships is the name of the game. We can’t say partnership on my terms anymore. The foundation for partnership is in capacity development for families. We are already networked. We need partnerships based on community relationships.”

Back in the slums of Nairobi, Anglican layman Francis Maina Mwangi is among the few men to volunteer as a health worker at St. John’s Community Center. Mwangi, 45, his wife, and their five children live a short distance from the community center. Mwangi works more than one job to support his family, and he visits about 25 homes weekly, taking time to build relationships and talk about HIV.

“After they hear the news about being HIV postive, we need to give hope to them, their families, and relatives,” Mwangi says. “The first step is to develop a relationship before the person is told. Then, when it is time to break bad news, the closeness is there.”

Mwangi’s standing in Nairobi’s Pumwani slum community was tested recently as he took visitors on a walking tour of the slum. As the group was gingerly passing by women washing clothes in muddy basins and barefoot children shouting the only English words they know (“How are you?”), a drunken man pushed his way in front of a visitor and shouted, “You are rich and I am poor! Give me food.” As onlookers stood speechless, Mwangi elbowed his way forward, responding, “You are not poor! You have two hands and two feet. You are rich.” Dazed, the man abruptly turned and marched away while yelling profanities toward the group. Afterward, Mwangi asks one visitor, “How would you be in relationship with that man?”

What Mwangi and other African Christians say they discovered in their personal crusade against the virus is best expressed in the native language si-Tswana: “Motho ke motho ka Batho” (“A person is a person through people”). For African Christians, servanthood in communion infuses their suffering with meaning. “When we invest in people and spend your life with the poor, God has a way of rewarding you,” Zambian Pentecostal pastor Banda says. “Your life has been worthwhile.”

Copyright © 2000 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.