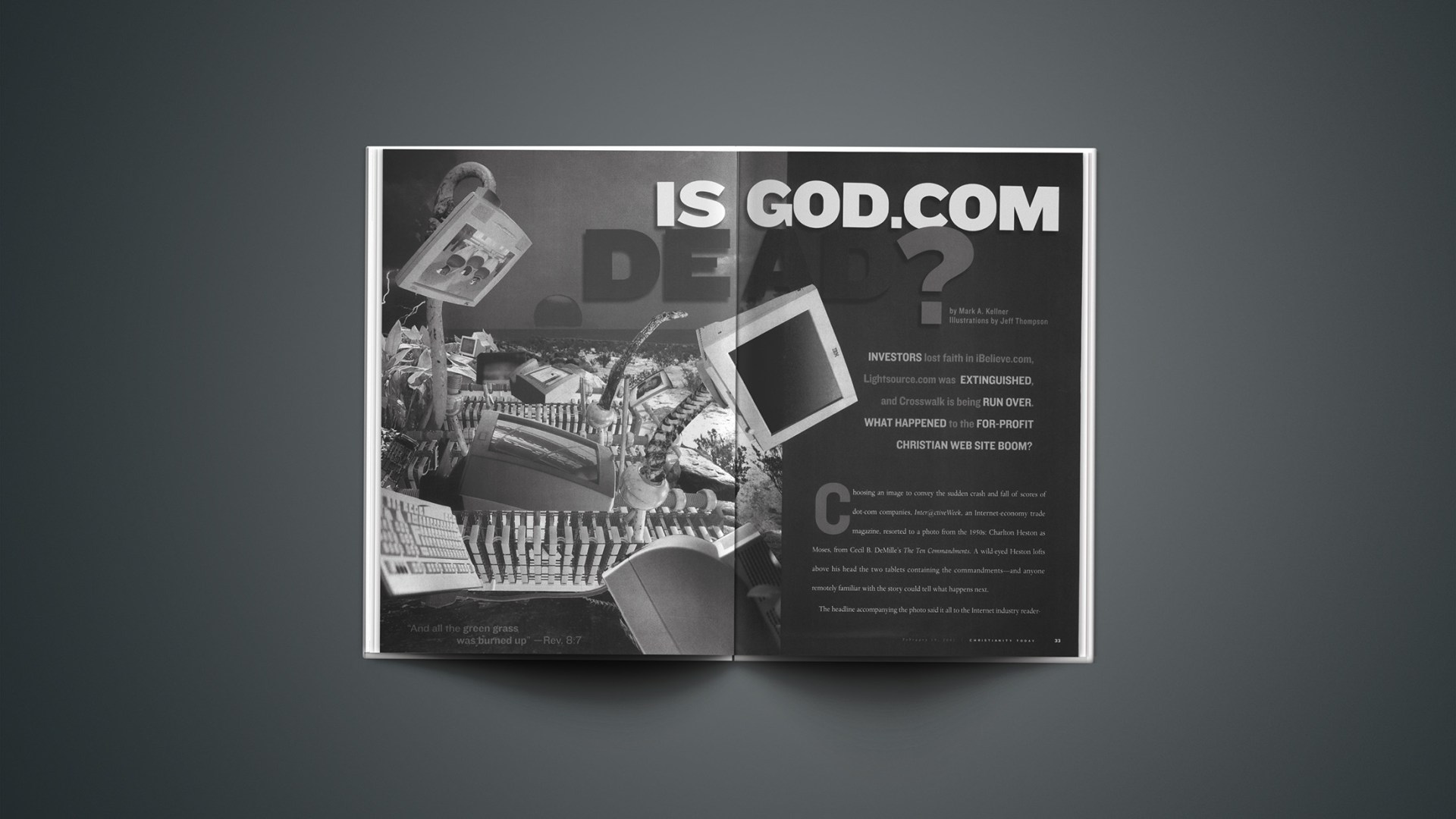

The headline accompanying the photo said it all to the Internet industry readership: old rules rule. The failure of dozens of cash-laden companies to reap vast sales through snappy Web sites and Super Bowl ads brought many of these high flyers fast down to Earth, with their firms and investors in shambles. The old rules of having a solid business plan and making a profit before launching out into the stock market were back with a vengeance.

Dot-coms aimed at the Christian market haven’t fared much better. Heavily promoted iBelieve.com lasted less than nine months before a sudden rapture to the land of deceased startups. Another, iChristian.com, made it from November 1999 to July 2000 before being swallowed up by Massachusetts-based Christian Book Distributors, a “brick-and-mortar” mail-order bookseller that also has a successful Web site (christianbook.com). And in December, Nashville-based Gaylord Entertainment pulled the plug on Christian Web sites Musicforce.com (a cd store) and Lightsource.com (which partnered with portal site Yahoo! to provide Christian audio programs).

Many that aren’t already dead are on life support. Crosswalk.com’s stock plummeted during 2000 and, despite high-profile deals such as an exclusive arrangement to cybercast Billy Graham’s Amsterdam 2000 conference, is losing ministry partners such as Charles Colson’s Prison Fellowship Ministries. Colson’s organization, the Salvation Army, Moody Bible Institute, and others are eyeing startup Christianity.com, which itself went through a round of layoffs and a direction change within a few weeks of launching.

The Internet has proven to be a tough harbor in which to pilot a nascent business, whether Christian or secular. Oddly enough, it wasn’t supposed to be that way. The Internet, pundits argued, was going to change the way we all did business, and make it faster and easier to build companies. “Internet time” became a catch phrase, referring to the hurry-up, supercharged atmosphere of a world where change could be computed in nanoseconds, where velocity was measured in kilobits-per-second.

Easy come, easy go

For the two years before the fall, however, it seemed that those old rules of business—like the laws of gravity—had been suspended, if not repealed. Time magazine featured Amazon.com founder Jeff Bezos as its “Man of the Year,” despite the firm’s not having made a profit. Ever.“IPO” became the mantra of 1998 and 1999, as companies theorized that Wall Street dollars were just as good as real revenues. But those who live by the Nasdaq ticker have found they can also die by the ticker.

Consider Steven M. Wike, for 13 months chief operating officer of Christian Internet portal Crosswalk.com. Wike (a onetime employee of Christianity Today International) in 1978 created Media Management, which sold direct-mail advertising to organizations that serve the Christian community. He has built it to $2.2 million in annual revenues from a base in Roanoke, Virginia.

As the Internet began to take off, Media Management created a Web site, goshen.net, which offered information, links, and e-mail bulletins to Christian leaders. The success of that site led Crosswalk to buy Wike’s business in June 1999, at the height of Wall Street’s love affair with Silicon Valley. A good chunk of the undisclosed purchase price was paid to Wike in Crosswalk shares valued at $9.70 each at the time of sale.

Wike, who also became editor in chief of Crosswalk.com, said in a statement at the time that he was excited about the move: “It is clear to more and more people in the Christian community that Crosswalk.com is assuming an increasingly high visibility and is creating something very special on the Web.”

That excitement apparently depreciated in the next 13 months. From a price over $12 per share in July 1999, Crosswalk shares were trading at about $1.44 per share when Wike resigned as coo in August 2000. By the end of the year, the price had shrunk to less than 60 cents per share, and Wike quit his last official tie to the firm as a member of its board of directors.

“I am saddened and disappointed with the outcome of the merger of Wike Associates Inc. and Crosswalk.com Inc.,” Wike wrote in a letter to James G. Buick, the former Zondervan CEO who is now chairman of Crosswalk’s board. That disappointment, while not explained in his resignation, likely included seeing the value of his Crosswalk shares plummet by more than 90 percent during the period, a worse percentage loss than has struck Amazon.com.

Conceded William Parker, the Crosswalk.com president who was replaced in January, “We bought his company largely for stock, and that’s no fun, needless to say.”

One Crosswalk.com insider—who insisted upon anonymity—said that Wike had criticized the firm for unsound business principles, such as neither “living within its means” nor expecting the Internet bubble to pop.

But as of press time, Crosswalk.com is at least still in business, and its stock is worth something. Consider the customers (and employees) of iBelieve.com, which came out of the gate in late January 2000 with $30 million in cash from investors, and Family Christian Stores—the nation’s largest Christian retailer—behind it.

“We set out to create the best site for Christians and families on the Internet, not by measuring ourselves against others in our niche, but by developing a comprehensive strategy that would put us among the best sites—like a Yahoo!, AOL, or Amazon.com—on the Web,” iBelieve president Jef Fite said in a statement at the time. “Now the real test begins.”

Despite strong backing and a multimillion-dollar ad campaign, iBelieve was apparently unable to “monetize” (to use the latest Internet buzzword) its business quickly enough.

The firm not only failed to get its message across in key prime-time shows—its efforts to buy advertising on CBS during the network’s Jesus miniseries and Touched by an Angel were rebuffed—it also failed to find additional funding and pulled the plug on October 20, 2000, less than nine months after its launch. In its 268 days of existence (including Sundays), iBelieve.com hemorrhaged more than $111,000 per day.

“We met or exceeded all of our traffic metrics, experienced revenue growth every month since launch and realized our goal of becoming the leading Christian Internet site,” Fite said in a news release announcing the shutdown. “However, like many other Internet companies, we were not able to raise capital given the current market conditions, and we [were] left without options.”

Too-fast company

Something more than just gravity took effect here. Call it a combination of the cockeyed optimism that has characterized American entrepreneurs from Ben Franklin to Henry Ford, the hubris of buggy-whip makers when Ford burst upon the scene, and a level of economic prosperity not seen in decades.At least that’s the assessment of experts such as Michael Wolff, media columnist for New York magazine and a battle-scarred veteran of the Internet business. Wolff, whose NetGuide book series became (briefly) a monthly magazine and a Web site, saw his own online dreams rise and fall in the early days of the Internet gold rush. He chronicled his experiences in a book, Burn Rate (Touchstone, 1999), which took its title from the very thing iBelieve.com’s flameout demonstrated: the speed with which a firm goes through or “burns” its seed capital.

What went wrong with the dot-coms, including iBelieve?

According to Wolff, it lies in trying to reap the rewards of a big business before rightfully claiming the status.

Those behind the dot-coms have, Wolff told Christianity Today, “created capital-intensive businesses, no different from lots of other businesses that might require years and years and years of investment before they yield a profit. Because most of them are asset-less businesses, they’re all investing in a very soft notion: building brand, achieving ‘mindshare,’ and so on.”

While an “exuberant” stock market—to use Federal Reserve chairman Alan Greenspan’s famous adjective—can support such investments, Wolff said, “Exuberance can go away very, very quickly.”

Now—as the dead and dying dot-coms learned the hard way—”There is categorically, flatly, no money available for any of these businesses. Unless you are in a position to radically restructure your business and make it self-supporting, you’re going to go out of business,” Wolff said.

One of the factors that dot-commers failed to consider was that while the Internet as an information-access technology was fascinating, not everyone has signed on yet. User rates are climbing, but not to the point that businesses can reach enough people to be profitable. Wolff believes Amazon.com would need to reach 99 percent of consumers—that is, have nearly everyone in America visit—in order to be profitable. But Internet use isn’t anywhere near that level, he added: cable television, which has been part of the American landscape for more than 40 years and a heavyweight player for at least 20, has still only penetrated 70 percent of U.S. homes.

The result: it costs more, far more, to build an Internet business than was suspected.

The Internet universe is “a lot smaller than people hoped it would be,” Wolff said. “Even with these fantastic rates of growth, it hasn’t grown to the place to be profitable.”

He says that thinking of the Internet as a “discrete business,” on the order of print publishing or brick-and-mortar retailing, is wrong-headed. “The Internet is merely a facilitating, transparent technology,” he said. “It becomes ingrained in a broad variety of behavior. It enhances all kinds of the ways that we communicate.”

Other analysts appear to be coming around to Wolff’s skepticism. Writing about Anthony Noto of bullish New York investment firm Goldman Sachs, the Associated Press reported his prediction in December that “as many as 10 of the 22 publicly traded e-commerce companies he monitors will no longer be alive by mid-2001.”

The reason? “Bad business plans.” In other words, the old rules have returned.

Knowing the day and the hour

When those rules come into play, they can leave lots of people in the lurch. Consider Peter L. Edman, hired by Crosswalk.com in the waning weeks of 1999 as editor of the News & Culture Channel.With corporate promises that his channel would be one of the cornerstones of the site, Edman busied himself with convincing several respected columnists, including Frederica Mathewes-Green and Terry Mattingly, to join his digital fray. He and his superiors swooned with the idea of creating the electronic equivalent of a literate, Christian newsmagazine.

So much for dreams. Ninety days after arriving, Edman was one of 30 Crosswalk employees, most of them “content creators,” shown the door. (He has since been hired by Prison Fellowship to edit BreakPoint Online.)

“It was a complete shock,” he recalled months later. “Even in the couple of weeks before the layoff, we had people coming in talking about major expansion. It was completely unexpected.”

But the move wasn’t beyond understanding, he added. “It always amused me the investment community was ignoring the fact that none of the online properties were making any money ever, and had no plans to.”

In announcing the changes last January, Crosswalk’s then-CEO, William Parker, stopped short of being that blunt: “We have never before made any public [profit and loss] projections, but we are determined to obtain a black bottom line as soon as possible. There are no guarantees, but we think we can obtain a net profit as soon as the fourth quarter of 2000.”

That fourth quarter has come and gone, but profitability still eludes Crosswalk.com, as evidenced by the depressed stock price, more layoffs, and exiting leadership. In a December 2000 interview, Parker said Crosswalk expects to be “cash-flow positive”—in other words, to stop bleeding money—”a year from now.”

And, while prophetic “date-setting” seems somewhat out of place for evangelicals, investment site Downside.com has a “deathwatch” page forecasting Crosswalk.com’s demise on February 15, 2001, right after online postage seller E-stamp.com and just before online mortgage broker E-Loan.com. (The prediction, specifically on when Crosswalk will run out of cash, is based on liquid assets and loss rate reported to the Securities and Exchange Commission.)

Crosswalk’s Parker will not be around to see the result. On January 11, 2001, Parker was dumped as CEO and replaced by editor in chief Scott Fehrenbacher (who previously served as head of the Institute for American Values Investing).

In a telephone interview, Fehrenbacher said the replacement of Parker—which was accompanied by another 15 layoffs and the consolidation of all Crosswalk offices into the firm’s Virginia headquarters—is an effort to recast the firm as one that makes its money the old-fashioned way: by selling something (in this case, Internet ads).

“The last six months of last year reflected an improvement in quality and depth of content, and quality of our traffic, which helps support increases we saw in ad revenue,” he said.

During that period, Crosswalk reported a 15 percent quarter-to-quarter growth in ad revenues, Fehrenbacher said. He expects such increases to continue in 2001, despite an industry wide slump in Internet ad sales.

Reflective of his confidence is a $500,000 annual advertising contract signed in January with Christian Book Distributors, which is becoming a kind of savior for Christian dot-coms (it also rescued Musicforce.com when Gaylord pulled out).

Fehrenbacher said the consolidation of offices and staff—offices in Colorado Springs, Roanoke, and Charlotte are being shut down—should bring continued improvements in content and lower costs. The firm’s September experience in moving its music channel offices from Nashville to Chantilly (acompanied by another set of layoffs) proved the point.

“By every metric since that move, the quality and the traffic of that channel have increased. Content is newer and fresher, yet we saved a great deal of money in that move, well in the six figures,” he said.

Does that mean that the selling point of the Internet—that geography was largely irrelevant and that workers can be located anywhere there’s a phone line—is a myth?

“Yes,” Fehrenbacher replies. “Will the Internet substitute for human relationships? No. But will it make for speedier access to information? Yes.”

New kid on the block

Three thousand miles to the west of Crosswalk.com’s headquarters, another Christian dot-com is keeping its employees together. In an industrial section of Hayward, California, due east of Silicon Valley epicenters such as San Jose, Cupertino, and Palo Alto, Christianity.com sits in modern but unremarkable office space. There’s no splashy sign on the building, and inside there are no desks; just folding tables and ergonomic chairs. The computers, monitors, and everything but the licorice in the snack area seems to be leased: “Property of” stickers sprout everywhere. There are the large whiteboards common to meeting areas in any startup. Here, however, is the odd Greek New Testament phrase along with the business projections.Attire is casual, but not as grungy as some dot-coms. But as in other Silicon valley companies, rank doesn’t really have its privileges here: the firm’s top two executives have partitioned cubicles not much larger, or better furnished, than anyone else’s.

But unlike Crosswalk.com, iBelieve.com, and other similar sites, Christianity.com isn’t trying to promote itself as a destination, but rather as an enabling technology.

“If you believe the gospel is the greatest message ever delivered, then you should endeavor to find the greatest medium in which to share it,” said Spencer Jones, chief operating officer of the firm.

Jones, who came to Christianity.com from the Christian Broadcasting Network (an organization that has invested $10 million in the Internet startup), said the goal is not to make “c.com” into a mega-portal for Christians, but rather to spawn thousands of other Web sites under one umbrella. Other funding and credit partners are Sequoia Capital, which invested $10 million, and Comdisco Ventures Group, which loaned $10 million for equipment and services.

“We’re not a ministry,” Jones says. “Our job is to enable those who save souls.”

In so enabling, Christianity.com has assembled a diverse group of ministries, from Prison Fellowship and its units to Texas evangelist T.D. Jakes to Catholic Way, a Roman Catholic ministry founded by longtime Pat Robertson associate Keith Fournier.

Asked whether such eclecticism risks alienating some users, Jones said Christianity.com “can’t go down a slippery slope. We can’t take sides.” Still, it has toned down its original organization into areas for Catholic, Orthodox, Messianic, and Protestant Christians in favor of a slimmer, more topical, and more Protestant-friendly navigation.

Christianity.com’s CEO is David Davenport, a Church of Christ minister who for 15 years headed Pepperdine University in Malibu, California. No stranger to burn-rate concerns, he jokes that he is “still running a nonprofit” by serving as the (actually for-profit) site’s CEO.

He describes the differences between a large liberal-arts university and a small high-tech startup as that between trying to command an ocean liner and piloting a speedboat. Already, he’s had to steer the venture around curves as sharp as any he faced on the winding Malibu Canyon Road that traverses his former workplace: “But even as a driver, I’ve been a broken field runner.”

That running included, weeks into the project this year, a scaling back of staff and refocusing away from content provision. As with Crosswalk.com’s now-diminished News & Culture channel, Christianity.com found there was apparently little profit in creating unique editorial content for the Christian market. Or, at least, in doing the creating (and paying) on its own.

Instead, the online venture is focusing on “syndicating” the content of its partner ministries. When groups such as Prison Fellowship, Jakes’s “The Potter’s House” or the Salvation Army sign on, they can elect to offer as much, or as little, of their content to other Christianity.com site users as desired. An individual church Web site can use a column by Chuck Colson; the Army’s War Cry magazine devotionals can depict life beyond the evangelical church’s outposts.

Such a tactic—one among several technical innovations aimed at ministries and groups that lack the time, money, or personnel to develop their own Web sites—is but one way in which Christianity.com is becoming something of an “applications service provider” to ministry groups. ASPs, as they’re known in the Internet field, offer a function via the Internet—bookkeeping and word processing are other examples—which the user accesses and pays for directly.

On Christianity.com, the payment can come in the form of accepting banner ads on the Web site, or monthly fees that scale according to a site’s size and traffic. The Salvation Army’s national organization, headquartered in Alexandria, Virginia, was facing estimates that topped $500,000 to redesign an existing Web site (salvationarmyusa.org) once hosted by Crosswalk.com’s servers.

“We were getting a lot of hits, but people were only staying on for three or four minutes,” said Salvation Army Capt. George Hood, assistant national community relations and development secretary for the group. “Users were looking for their local Salvation Army. We’ll see if we can create a stickier environment” with Christianity.com, he said.

The group is going to migrate content from its War Cry biweekly magazine to the new Web site and allow syndication. Instead of paying for the site, Salvation Army officials told Christianity.com to bring on the banner ads—with the sole exception of the American Red Cross, with which the Army competes for emergency relief donations.

Hood said the Army’s “commissioner’s conference,” a board of directors for the national group made up of regional leaders, “had no problem with the ads, because they ignore the ads anyhow.”

Of course, Christianity.com is hoping users don’t ignore the ads, and is seeking to fine-tune the placement of banners as much as possible. Still, anomalies crop up: the Catholic Way pages featured ads for Tyndale’s Left Behind series—which isn’t terribly friendly to Catholic theology—at one viewing.

Perhaps the greatest appeal of Christianity.com to ministries—along with its flexible cost structure—is its whiz-bang site management tools, aimed at users who don’t have much Web design or programming skills. About $2 million went into this system, coo Jones said, and, yes, the for-profit Christianity.com could license that technology to other, nonrelated firms. But for the site’s users, the payoff seems to be ease of use.

“We feel it is a win-win, because of their technical skills and flexibility,” the Salvation Army’s Hood said. “It seemed to be a much more economical approach to have the horsepower and bells and whistles without a tremendous developmental cost.”

Adds BreakPoint Online editor Peter Edman, “We’re reasonably happy with what we’re able to do. They seem to be doing it better than many. They are very professional and continuing to improve.”

Davenport, Jones, and other employees of Christianity.com are betting that this will parlay into a wide range of deals, leading to a potential ipo at some point. For now, however, staying alive as a business might be as satisfying as a stock exchange ticker symbol.

The first shall be last?

Christianity.com wasn’t the first to promote itself as merely an umbrella for other Christian organizations. Grand Rapids, Michigan-based Gospelcom.net also bills itself as “an alliance of Christian organizations dedicated to spreading the gospel over the Internet’s World Wide Web.” As such, it’s a nonprofit (and thus not really a dot-com), albeit one with some e-commerce components.The site is the 1994 brainchild of Gospel Films’ marketing director Duane Smith and Calvin College professor Quentin Schultze, who remains an adviser to the group. It’s backed by the Gospel Films board, chaired by Amway co founder Rich DeVos and Gospel Films president Billy Zeoli. Gospelcom was one of the first Christian sites, and today is an umbrella for various online ministries and Bible research tools.

It’s also the disputed victor so far in the battle between Christian Web sites. Gospelcom has snared 190 Christian ministries and organizations as members, ranging from InterVarsity Christian Fellowship to Taylor University. Even more appetizing to competitors and investors, it has also consistently ranked high in some media surveys, pulling the top ranking in a MediaMetrix review of religion sites with 773,000 unduplicated visitors in the month of November (Crosswalk.com was second, with 715,000). It’s a long way from Amazon.com’s 19.1 million unduplicated visitors during the same period, but it’s enough to have Christianity.com salivating—and trying to lure Gospelcom’s ministries away.

But Schultze says Gospelcom has a better chance of survival than its dot-competition not just because of its user numbers, but because it doesn’t have to make boatloads of money.

“I don’t see how a Christianity.com or a Crosswalk.com or any other major for-profit Christian portal could become profitable,” Schultze says. “Christianity.com has some wonderful ideas, but I see no way they can build a long-term, profitable business based on those ideas.” The challenge is particularly tough, he says, with the change in capital markets.

Schultze, whose latest book is Communicating for Life: Christian Stewardship in Community and Media (Baker, 2000), is also doubtful that a for-profit business can fill the communications needs of smaller ministries. “The history of evangelicalism in America shows that the real energy and drive come from individual believers and from their close-to-home ministries, not from large businesses or organizational structures. I don’t think that any top-heavy organization with proprietary technologies will attract a lot of ministries.”

Some Christian groups, Schultze laments, have confused the blinding wealth of yesterday’s Internet with the eternal demands of the gospel. “Christians need to be wise stewards of new technologies and capital resources, avoiding the public hype while simultaneously looking for sound ways of taking advantage of new opportunities,” he said. “A lot of the public hype about the Internet was driven by false thinking, idolatry that put more faith in technology than God, greed that sought to cash in on IPO money, stupidity that overlooked sound business practices, and arrogance that assumed perfect knowledge of the nature and impact of new media technologies.”

Maybe so. But while the battle of the Christian dot-coms has seen its share of casualties, it’s probably far from over.

Mark A. Kellner writes computer columns for both The Washington Times and Los Angeles Times.

Copyright © 2001 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.

Related Elsewhere

Be sure to read today’s related story, “‘We All Believe In Something’ | And Beliefnet believes the answer to serving both God and Mammon lies in being as interfaith as possible.”Visit the Web sites of Christianity.com and Crosswalk.com, as well as Gospelcom.net.

Crosswalk’s latest stock price and press releases are available at Yahoo finance and other sites.

“Old Rules Rule” from InteractiveWeek.com discusses how “from business basics to legal precepts, Internet companies are discovering. … that they can’t defy the fundamental rules of marketplace physics.”

Find Michael Wolff’s media columns about everything from Tim Russert to the AOL Time Warner merger at New York Magazine’s site. Burn Rate, Wolff’s book about his own Internet business experiences, is available from Amazon.com and other retailers.

Quentin J. Schultze’s homepage offers a free Internet for Christians Newsletter if you’d like to hear every two weeks about the latest news among online Christians. His site also links to all the news stories he has been interviewed for.

Schultze’s Internet for Christians and Communicating for Life are available from the Christianity Today bookstore and other book retailers.

The Christianity Today Weblog has been covering the dot-com bust for a while. Some items include:

Crosswalk.com Lays Off Quarter of Its Staff, Replaces CEO (Jan. 12, 2001)

Gaylord to Shut MusicForce.com, LightSource.com, and Other Internet Sites (Dec. 6, 2000)

Plug Pulled on IBelieve.com (Oct. 20, 2000)

As Crosswalk.com Cuts Staff and Closes Office, Other Christian Web Sites Flounder Around It (Sept. 27, 2000)

Former Goshen.com Head Steps Out of the Crosswalk (Sept. 20, 2000)