In Rwanda, evil has a name, an address, and a bunk bed. At the Kigali Central Prison entrance, a 10-foot strand of twine and an elderly Rwandan armed with a rifle are the only bars to entry. Deo Gashagaza, Prison Fellowship Rwanda’s executive director, drives up to the lush hillside entrance and the guard lowers the string, waving us through. The Ministry of Justice has granted CHRISTIANITY TODAY a rare day pass to visit this prison in Rwanda’s capital.

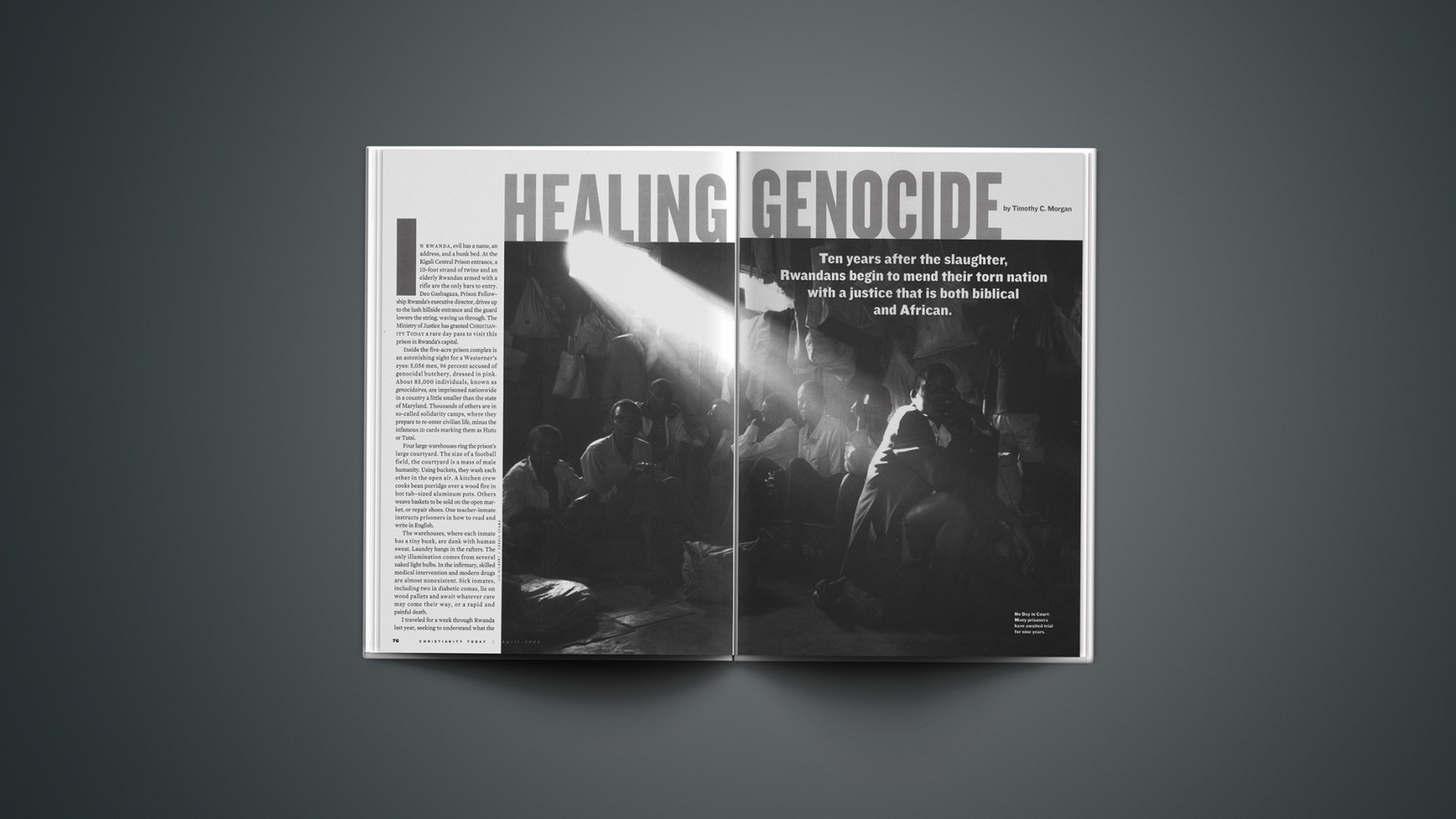

Inside the five-acre prison complex is an astonishing sight for a Westerner’s eyes: 5,056 men, 96 percent accused of genocidal butchery, dressed in pink. About 85,000 individuals, known as genocidaires, are imprisoned nationwide in a country a little smaller than the state of Maryland. Thousands of others are in so-called solidarity camps, where they prepare to re-enter civilian life, minus the infamous ID cards marking them as Hutu or Tutsi.

Four large warehouses ring the prison’s large courtyard. The size of a football field, the courtyard is a mass of male humanity. Using buckets, they wash each other in the open air. A kitchen crew cooks bean porridge over a wood fire in hot tub-sized aluminum pots. Others weave baskets to be sold on the open market, or repair shoes. One teacher-inmate instructs prisoners in how to read and write in English.

The warehouses, where each inmate has a tiny bunk, are dank with human sweat. Laundry hangs in the rafters. The only illumination comes from several naked light bulbs. In the infirmary, skilled medical intervention and modern drugs are almost nonexistent. Sick inmates, including two in diabetic comas, lie on wood pallets and await whatever care may come their way, or a rapid and painful death.

I traveled for a week through Rwanda last year, seeking to understand what the genocidaires did, and how Christians, ten years after the slaughter, are pursuing reconciliation. I spent time with government officials, survivors, nurses, doctors, missionaries, former soldiers, and pastors. The price in lost lives and lost opportunities has been extraordinarily high for this nation, but a new space for healing is being created in a uniquely biblical and African way.

Administering Mass Justice

“We killed our people. The physical genocide was a reaction to spiritual genocide, spiritual emptiness,” Emmanuel Kolini, the Anglican archbishop and Rwanda’s most influential Protestant, told me as we talked at St. Stephen’s Cathedral in Kigali. “Some people don’t think sin is real. Rwanda is a witness. Sin is real. It is bitter. It’s a fire. Rwanda has helped me understand the depth and weight of sin.”

The roots of Rwanda’s ethnic bloodletting run deep. During colonial rule, Westerners gave preferential treatment to Tutsis in education and skilled jobs. Hutus resented it deeply. A 1959 coup deposed the Tutsi monarchy, leading to Hutu majority rule. That set off decades of bloody reprisal and counter-reprisal. Tens of thousands of Tutsi and Hutu slaughtered each other with few consequences.

In 1990, Tutsi soldiers based in Uganda launched a civil war against the Hutu-controlled government. After four years of fighting, Tutsi and Hutu leaders prepared to share power. But on April 6, 1994, a jet carrying President Juvenal Habyarimana was hit by a missile that killed all on board. (No one has been charged with that assassination, but Hutus suspected Tutsis.) Within hours, a well-organized retaliation against Tutsis began. During the next 100 days, Hutu militias, government soldiers, and everyday Rwandans slaughtered Tutsis and moderate Hutus (all told, about 8,000 a day) with machetes, hand grenades, farming tools, arson, and bulldozers. The killing stopped only when the Tutsi-led Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) took control of the country on July 4, 1994.

In the aftermath, Rwanda’s criminal justice system was overwhelmed. More than 100,000 genocidaires were crammed into 19 prisons. At first, Rwanda attempted to place the accused on trial. But during one two-year period, more genocidaires died of disease in prison than were tried. Also, Rwanda’s execution of 22 genocidaires by firing squad in public triggered international outrage. Critics said the executions would only bring about more ethnic reprisal. In the meantime, the number of Rwandans on death row continued climbing. Rwandans who sought some measure of justice were caught between the proverbial rock and a hard place.

A ‘Third Way’

A short time after the genocide, Desmond Tutu, then the Anglican archbishop of Cape Town, South Africa, visited Rwanda and publicly called for mercy for the genocidaires. He championed restorative justice as a “third way” between so-called victor’s justice that harshly punishes the guilty and the temptation of national amnesia.

Tutu’s suggestion offered Rwandan Christians a third way. It is a way reaching into their cultural past as well as stepping into an uncertain future. In 1999, the Rwandan government, realizing that it was impossible to bring so many killers to a Western-style trial, revived Gacaca, the precolonial court system. It’s named after the grassy area where village elders would gather to settle disputes. The Gacaca system supplements the nation’s other courts and the U.N. genocide tribunal (headquartered in Tanzania). Gacaca is perhaps the largest modern-day experiment in using community courts to determine the fate of genocidal felons.

In some aspects, Gacaca echoes the methods of Tutu’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission, put into place after black-majority rule was implemented in South Africa. That panel had the legal authority to grant full amnesty, provided officials and other individuals admitted guilt and sought forgiveness.

Tutu’s conceptual framework for justice and reconciliation, spelled out in his influential book, No Future Without Forgiveness, is African and scriptural. South Africa’s Zulus have a proverb: Umuntu ngumuntu ngabantu (“A person is a person through persons”). Tutu uses the word ubuntu (“compassionate human interaction”) and other African cultural concepts to develop a theology in which personhood is anchored in community. “A self-sufficient human being is subhuman,” the now-retired Tutu writes in a related book, Reconciliation. “God has made us so that we will need each other. We are made for a delicate network of interdependence.”

Meg Guillebaud, a British missionary who trains Rwandan clergy, echoes that theme. “In the old days, no individual was ever considered to have committed an offense. It was regarded as being committed by the whole family.” The families of an offender and a victim would assemble before village elders to determine the facts as well as restitution.

For minor crimes, one family would extend imbabazi, the word in Kinyarwandan (the indigenous language of Rwanda) for mercy. It literally means “a place where you would receive all the love and care a mother would give.” In more serious offenses, mercy was not feasible and relations between families would be severed.

Guillebaud-author of Rwanda: The Land that God Forgot?-said Western missionaries usually emphasize individual guilt and the individual’s need to repent. As a result, the Rwandan family-based means for restoring relationships was lost. “Hebrew thought forms are much more like Africans’ in their stress on family responsibility,” she says. The narrative of Joshua 7-the stoning of Achan, his family, and possessions for theft-provides Western Christians a point of reference for better understanding the African cultural context.

She says African Evangelistic Enterprise is training Christians in how to cooperate with the Gacaca courts as well as church-based reconciliation efforts. “Right through the land are large roadside signs about Gacaca: ‘Tell what you know. Admit what you have done. The truth will heal the land.’ Rwandan Christians offer the world this awareness of what the cross can do in healing pain and restoring an ability to forgive.”

Each Gacaca will have the ability to determine guilt and consequences-whether the accused should face additional prison time or pay restitution. But the emphasis will remain on truth-telling and reconciliation. Confession will have a prominent place in the process and will influence the severity of any penalty.

Gacaca is not foolproof. Ibuka, an advocacy organization of survivors, reported that four witnesses who were prepared to testify in Gacaca courts were murdered during the second half of 2003. “These killings are well-planned and target one section of people with the intention of keeping their lips shut,” the organization said. Also, police have rearrested 787 (of 25,000) parolees who came under new accusations after release.

Experts in restorative justice recognize its limitations. A victim who has been reconciled to his neighbor may still be homeless and unemployed. Howard Zehr, an American authority on restorative justice at Eastern Mennonite University, told me during a stateside interview that Gacaca was not designed to deal with genocide. He said, “Victim and offender are so intermixed in these communities, there’s been concern about abuses in its practice.”

That being said, there seems to be no more hopeful prospect for national healing than supplementing the justice system with both Gacaca and Christian leaders committed to full reconciliation. In my travels, I met three individuals in particular who are working toward restorative justice in Rwanda in impressive ways.

A Warden’s Ministry

Inside the Kigali prison complex, Warden Muligo Faustin invited me into his sparsely furnished office. Large windows overlook the prison courtyard. On a worn chalkboard behind his desk, his staff keeps the daily count of prisoners.

Faustin, a lean man with penetrating eyes, has had an unusual career. Before working as a prison warden, he was a social worker for World Vision Rwanda. He found his outreach did not fully address the injustice that widows and orphans suffered during the genocide.

In mid-1994, there was an urgent need for prison administrators. He took an exam and was hired to run a prison in a smaller city. “I was there to change the world,” he said. In time, Faustin took on the warden’s job in Kigali, one of the nation’s largest prisons.

“Before I was hearing widows, orphans, and survivors,” Faustin said. “Now I work directly with the genocidaires. It’s a burden on my heart. The genocidaire is a human. The survivor is a human. I have to hear them as a human.”

Prisons are deeply involved in the Gacaca process. Prison counselors, including pastors, prepare the accused as well as family members for their Gacaca hearing. Faustin said he personally supervises that process. “I am a guide for the prisoners. The prosecutor and I have to agree to release.

“The prisoners think they are seen on the outside as something very terrible. When a genocidaire starts to tell the truth of what they have done, families react very strongly: ‘No! That’s not you. Don’t talk about that. Hide it.’

“But the genocidaire should say, ‘I have to talk about it.’ Reconciliation has to start inside the prison.” He said chaplains, local pastors, and others are going “story by story” through the prison population. So far more than 1,500 have confessed to crimes.

A couple of days after my initial visit, I returned to the prison on Saturday when families visit. The setting was remarkably festive. Hundreds of genocidaires’ family members stood silently across from their fathers, husbands, uncles, sons, or brothers as an inmate gospel band and red-robed prison choir performed with an electric guitar, hooked up to a battery-powered amp.

Two English-speaking inmates, named John and Innocent, agreed to talk. They were clean-cut and cheerful. Shouting over the raucous 23-voice praise choir, Innocent said, “I’m not afraid to face [Gacaca]. It is a justice.

“I want to return with my family, not only for myself but also for the others so we can be together. I’m eager to get my life back together.” He is married and his wife is in school.

John (wearing a red baseball cap with the words GOD IS GREAT) told me, “Pastors have come to do programs and explain about Gacaca. We are willing to be taught, but maybe it’s already too late.” During the genocide, “Everyone killed someone, and it was not a crime.” Ordinary Hutus had a fateful choice: Kill or be killed.

Rwanda will have about 9,000 Gacaca courts when the system is functioning fully. “The point is to restore relationship, even though there will be punishment,” said Anastare Balinda, administrative counselor for the Gacaca courts, during an interview at the Department of Justice. “Genocide survivors are happy about Gacaca. It will be their opportunity to find out how their relatives died, who took what, and what happened.”

From Holocaust to Genocide

If any person in Rwanda merits being in a category of one, it is an American missionary, Sonja Hoekstra-Foss. She has served in central Africa for 17 years and many consider her to be reconciliation personified. Her original job description never encompassed what has turned out to be Sonja’s important role: Through her example, helping Rwandan survivors learn to talk about hate, terror, survival, and forgiveness. She wears a Star of David and a Cross around her neck.

Sonja is a Dutch Jew. During the Holocaust, Sonja’s parents (the Khans) placed her into hiding with the Hoekstras, a Dutch Reformed family in Eindhoven, Netherlands. In order to adopt her, the Hoekstras pledged to raise her as a Jew. She went to synagogue and Hebrew school, and celebrated Jewish holy days.

Most Khan family members died in the Holocaust. As a young adult, she immigrated to America and in time came to faith in Christ after reading the Gospel of Matthew. But her past always haunted her, driving her to answer the questions Who am I? and Why did I survive?

At a Boston church in the 1980s, Sonja attended a conference on healing of memories. There she encountered a German woman, who as a child was drawn into the Nazi culture of the 1940s. During a small-group breakout, Sonja spoke to the woman symbolically: “In the name of Jesus Christ, I forgive you for killing my parents!” The two embraced and wept. Afterward, Sonja was invited on short-term missions trips to share her gripping story of healing.

Some years later, Sonja accepted a full-time appointment to work alongside Bishop Kolini in Zaire (Congo). In 1994, she served as treasurer for SOS Rwandan Orphans, one of the few African-based efforts to provide direct aid to the survivors of the genocide. Traveling into Rwanda with $11,000 cash on her person in a van containing 1,000 kilos of clothing, medicine, and food, Sonja and a small ministry team crossed the border.

On their arrival, they searched Kigali for a struggling orphanage. Their cash and material goods ended up on the doorstep of Damas Gisimba, a kind of African Oscar Schindler (the German industrialist who saved 1,200 Jews from annihilation). Gisimba, a child of a Hutu-Tutsi marriage, personally intervened during the 1994 slaughter to save 400 Rwandans at the orphanage his father founded in 1980.

Later in 1996, Sonja and other missionaries helped Tutsi and other Christians escape certain death as war spread through central Africa. At a meeting of Rwandan church leaders, she shared her story of Holocaust survival. An overjoyed Rwandan pastor came up to her and said, “I am happy to hear that God has called you to come here. Your story is our story, and you belong here.”

Since relocating to Rwanda, Sonja has built relationships with many survivors, listening to their hopes and sorrows. “I feel Rwandan and this is home,” she said.

A few years ago, Sonja was walking home when a young Rwandan woman stopped her in the street. “Do you remember me?” the woman asked.

“Your face is familiar, but I just can’t place you right now.”

“I want to give you this,” the woman said, handing Sonja the equivalent of $400 in Rwandan francs, about four months’ wages. “Thank you for enabling me to flee.”

Sonja wanted to give the money back but realized that would have been culturally offensive. She felt obliged to take it, and she used it all for ministry. “It was incredible,” she said. “If you do God’s work, he will provide everything.”

In talking with survivors, Sonja says she feeds them insights from her own experience: God’s plan is to make you prosper, not harm you. We forgive, but we cannot forget. There is level ground at the foot of the Cross.

Sonja took me to visit Theodore, a survivor from Gikongoro who lost many family members, including his father, in 1994. “Reconciliation is possible,” he said. “It’s a process, not a game to play at.” Our interview took place in his tiny, two-room apartment, about the size of a king-sized bed. As he spoke, he carefully removed his trousers to show me the deep scars on his legs from gunfire and machete assaults.

“We have to accept reality step by step. They have to understand the bad they did,” he said in voice heavy with grief. “If there had been no genocide, I would have finished my university degree and had a job. I could have had my own family. A wife and children! I pray a lot to forgive.”

Courage in a Post-Genocide Church

Rwandans have a famous saying: “God travels around the world during the day, but returns to Rwanda at night.” Archbishop Kolini told me Rwandan Christians must reinterpret such cultural expressions as God’s invitation to deeper relationship. He said Rwandans, after the genocide, understand better that “their refuge is in God, not in religion.”

“God is with them and telling them: I’m still here. I’m not dead. I haven’t abandoned you.”

Rwanda by 1994 was 90 percent Christian and had a rich history of renewal, dating from the famous East Africa Revival in 1929. “They were babies like the church in Corinth,” Kolini said. “That’s how I look at the church of Rwanda before genocide.”

Since the genocide, the religious demographics have been changing, with Protestants surging nearly 20 percent in half a decade. Though Catholics have declined (by 7.6%), they still make up 49.6 percent of the population. Protestants now account for 43.9 percent (and Muslims, 4.6 percent). But Christian tradition and ethnic background have not been as crucial as simple acts of courage.

A Tutsi, Kolini took office as archbishop in 1998, and soon after, he experienced a defining moment over a simple, midday meal. He had traveled to Rwandan’s southeastern border for a confirmation service. Thousands of Hutu refugees were encamped in the vicinity.

It was a dangerous situation to step into, with many genocidaires hiding in the camp. But “as the archbishop, I had to go,” Kolini said.

After the service, they all gathered to eat. One Rwandan came up to Kolini, urgently asking him, “Aren’t you afraid of being poisoned? Are you going to eat?”

Shocked, Kolini thought to himself: If I don’t eat, then I have spoiled my gospel. He carefully replied, “I have to sit down. These are my friends in the Lord and the gospel.”

Breaking bread, Kolini said, has become one tangible step toward reconciliation. During my interview, Kolini asked, “Did Jesus ask his Father whether it was safe to come into the world? He had to obey. If the Lord is calling you, nobody should ask you a question about coming to Rwanda, even if there is no security.”

I asked him where he thought God was during the genocide.

“It’s not an easy question. To me, God was there: Invisible, but visible. Not to people who organized and executed the genocide, but visible to the victims. It was not God’s will for genocide. At the same time, he was welcoming his people home. God is mysterious. I grow when God reveals his mystery.”

Kolini believes that not just the Hutu militants are on the hook for what happened during the genocide. One analyst has said that other than the government, churches bear the heaviest responsibility for not stopping the genocide. Three Rwandan Christian leaders await a U.N. trial in Tanzania. A leading Adventist pastor and his son were convicted. (A Catholic bishop has been acquitted and an indicted Anglican bishop died in U.N. custody.)

“When Rwandans were crying out for help, the world was silent. Quiet!” Kolini said in anguish. At the same time, he wants to point out, “We forgive the genocidaire. We also forgive the U.N. and the rest of the world.”

Among Rwandans, then, honest storytelling has become a strong catalyst for reconciliation and remembrance. Missionary Guillebaud shared with me Deborah Niyakabirika’s story, chronicled in a World Vision Australia video. Her son was murdered, in an isolated act of ethnic vengeance, three years after the genocide.

Months after the killing, a young man visited Deborah. “I killed your son,” he said. “Take me to the authorities and let them deal with me as they will. I have not slept since I shot him. Every time I lie down I see you praying, and I know you are praying for me.”

Deborah answered, “You are no longer an animal but a man taking responsibility for your actions. I do not want to add death to death.”

Then Deborah did the extraordinary. “But I want you to restore justice by replacing the son you killed,” she continued. “I am asking you to become my son. When you visit me, I will care for you.”

Today, that young man is an adopted member of her household.

Timothy C. Morgan is deputy managing editor of Christianity Today.

Copyright © 2004 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.

Related Elsewhere:

See also today’s sidebar on restorative justice.

Author Timothy Morgan discusses the article in his Inside CT.

More on Rwanda includes:

Influence of Roman Catholic Church in Acquittal of Rwandan Bishop Debated | Augustin Misago cleared of 1994 genocide charges. (June 20, 2000)