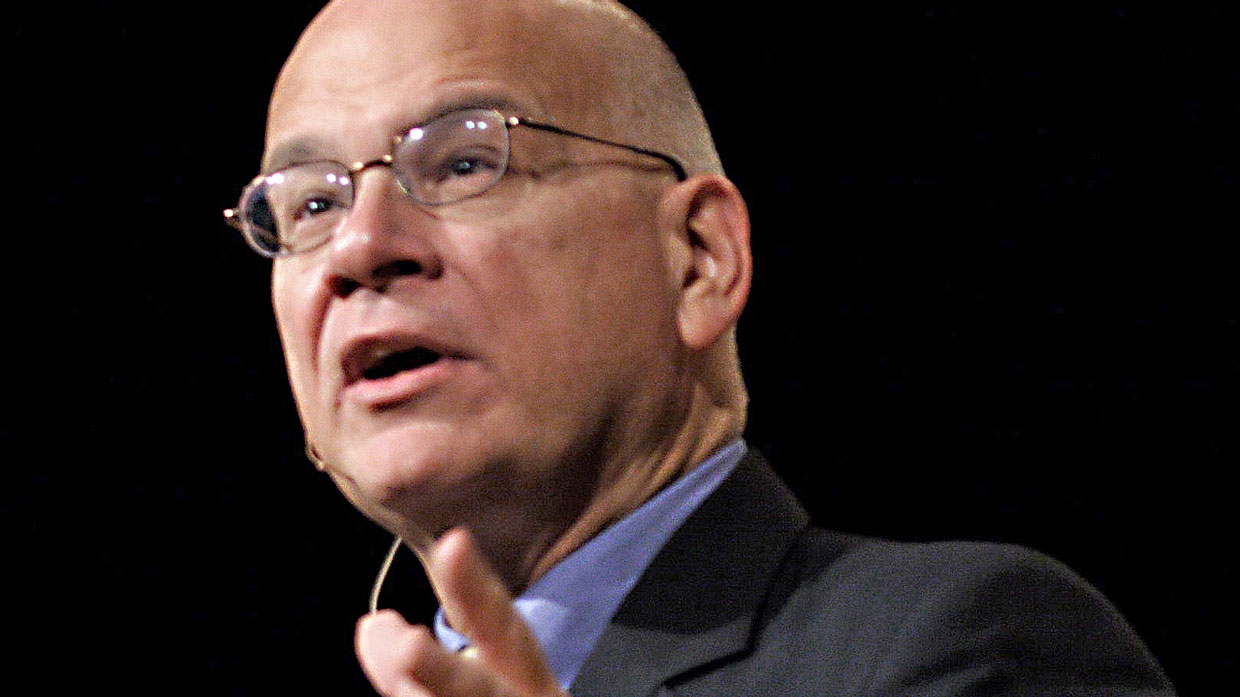

Several years ago, Timothy Keller, pastor of Redeemer Presbyterian Church in New York City, published The Reason for God, a book that introduced skeptical readers—and many a believer—to logical arguments pointing to the existence and goodness of God. Encounters with Jesus: Unexpected Answers to Life's Biggest Questions, based on previous talks given to students and businessmen, is a kind of companion volume, that lays an emotional groundwork for embracing the rationality of Christian faith. Owen Strachan, professor of theology and church history at Boyce College, spoke with Keller about how discovering Jesus can change people's hearts and lives.

Encounters with Jesus: Unexpected Answers to Life's Biggest Questions

Viking Drill & Tool

240 pages

$3.49

You've been doing apologetics and evangelism for an audience of skeptics for years. Why this book at this time?

There are ten chapters, and the first five were talks I did at Oxford University in February of 2012. Every three years, the Oxford Inter-Collegiate Christian Union does a campus-wide mission, and they bring in speakers to speak at lunchtime and in the evening. It's a really big deal, and very well done. It's an honor to be asked. I gave five talks that were the first five chapters of the book—Nathanael, Nicodemus, the woman at the well, Mary and Martha, the wedding feast, and Mary after the resurrection. Each of them was an example of someone whose life was changed by encountering Jesus, and so that's the basis of the book.

This book seeks to reach the heart, though I give much philosophical argument. I don't think people would actually sit down and listen to The Reason for God unless they already might wish that Christianity does make sense. A lot of people aren't going to give the time it takes to think it through if they don't care if Christianity is true. But if you expose people to Jesus' claims and offers, that makes people say, "That would be great—living water." It has to make emotional and even cultural sense to people before they sit down and decide if it makes rational sense. Jesus does that—he resonates with people. So this book is more of a precursor to something like The Reason for God.

Who should read this book?

The first five chapters are about how Jesus changed people's lives, and the last five chapters are about incidents in his life. It's basically trying to give you a thoroughgoing sense of the gospel that is radically Jesus-centered. It's a good book to give a non-Christian, but it's also a book to give a Christian that doesn't understand their own faith. It's about the Christian life but is told through the lens of Jesus' life.

The book is for the person I tend to run into in a place like New York or Oxford. It's trying to present the gospel in these cultural centers to people who are experts in their own area. They're very educated and very knowledgeable. So when you come to them and talk about faith, philosophy, religion, and belief, they expect that you will know the background. But you still have to summarize and explain it for intelligent people who may not know theology but who have worked through major kinds of data in other fields.

If I'm talking with a doctor, and I talk to them as if they're capable of understanding concepts and distilling information, that's a fit. This matches the contexts in which this book was created—the last five talks were given to businessmen at the Harvard Club. For many years, there was a meeting where Christians could bring non-Christian friends. So of course the book is not going to be simplistic. These people are not going to be excited about simplistic material. That said, the books are fairly down-to-earth and simple.

You state that we all know there's a standard by which we will be judged—"there is a bar of justice somewhere for all of us." Could you unpack this idea? Why is it relative today?

What that means is in our hearts, we know that morality's not relative. We know that there's a standard by which people are going to be judged regardless of how they feel. We bear witness to that when we may say morality's relative, socially constructed, evolution and culture determine what we feel is right or wrong, but there's no real standard. But then, deep in our hearts, we do feel when someone does something wrong that they should be accountable. So I was trying to tell people what they intuitively know to be true is true. There is such a thing as objective moral truth.

Many of us could go years without saying words like "Ascension of Christ." Can unfamiliar doctrines have a practical impact in people's lives?

If you read through the Puritans, they were wonderful at taking every doctrine in a systematic theology book and giving you 60 applications of it. They'll take the high priestly intercession of Christ and they'll say "Here are where 8 ways your life will be changed by this." They were called Protestant scholastics, but they learned from the medieval church to think things out and divide them up. Their sermons can be tedious. But they showed me that you can think out the practical applications of doctrines.

What response have you seen from your on-the-ground work preaching and teaching these truths?

This is completely unscientific, but my feeling always has been that when the gospel's preached in a place like New York, there are three skeptical people that come in the door. One will be offended. One will be indifferent: "That was nice and interesting." And one person says "That's kind of intriguing. I never thought of that."

After 9/11 most churches had this huge influx of people in New York City. Every church was packed to the rafters. My son got a couple of calls from people he knew who grew up here who never went to church and they asked to come to church. They felt the need for connection. Every church was packed out—it was astounding. Within two months, it went back to normal. Redeemer held on to about one-third of the people. Basically, about 2000 people showed, and about 600-700 stayed around. That was my evidence for my model. That's a long time ago.

In an increasingly hostile culture, how should the church present itself?

We shouldn't get shrill, that's for sure, or defensive. That would only make things worse. We shouldn't be caustic, and we shouldn't in any way back down or hide. If we play down what we believe it will look like cowardice. It's one thing to play something down so that people major on the majors—so people focus on Jesus and don't get distracted. In sum, you keep from the foolishness of either being too afraid or too accommodating.