New York City gave Billy Graham a national stage like no other US city when he arrived in 1957. And the evangelist saw a special opportunity in its ethnic diversity, with “more Italians than Rome, more Irish than Dublin, more Germans than Berlin, more Puerto Ricans than San Juan.” He also knew that one out of every ten Jews in the world lived in New York.

Graham capitalized on the city's ethnic character, notably inviting Martin Luther King Jr. to offer an opening prayer, preaching a Saturday afternoon Spanish service through an interpreter, and in his free time meeting with various Jewish groups. He developed a long-lasting friendship with Rabbi Marc Tanenbaum, then director of the Synagogue Council of America. Both were men of enormous influence in their own circles, and they did not hesitate to use their influence to advance each other's interests.

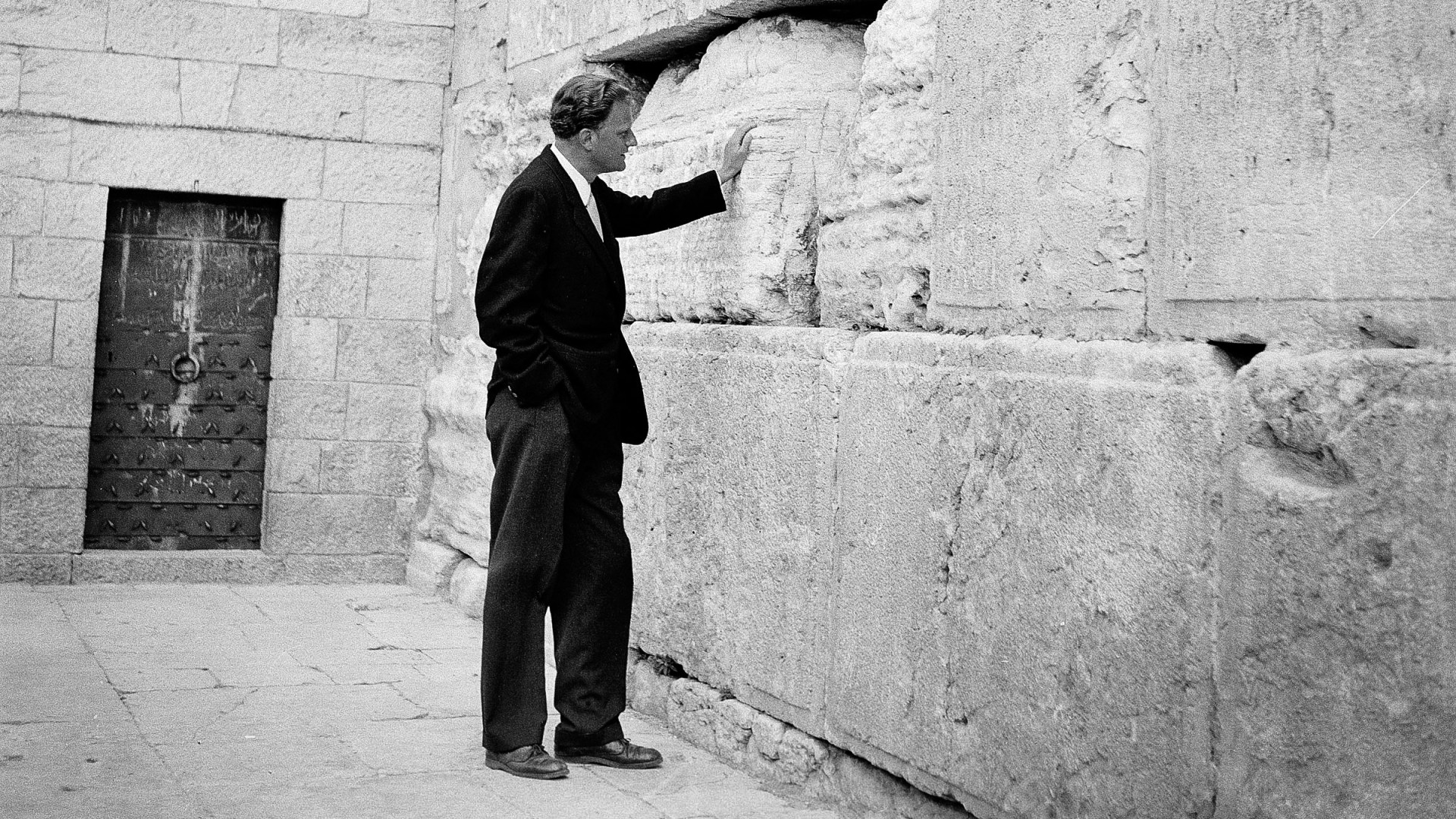

Over the years, the Jewish community recognized Graham for his key role in interfaith relations. In 1960, it was Israel Prime Minister Golda Meir, presenting him with a Bible inscribed, “To a great teacher in all the important matters to humanity and a true friend of Israel.” In 1969, it was the Torch of Liberty Plaque awarded by the Anti-Defamation League. In 1971, it was the International Brotherhood Award from the National Conference of Christians and Jews. In 1977, it was the American Jewish Committee's first interreligious award, with Tanenbaum declaring, “Most of the progress of Protestant-Jewish relations over the past quarter century was due to Billy Graham.”

The community's appreciation for Graham stemmed in part from his repeated refusal to “single out the Jews as Jews” in his evangelism—despite his role as the spiritual grandfather of the Lausanne Consultation on Jewish Evangelism. In 1973, he distanced himself from the Key 73 evangelism campaign for its attempts to target Jews. In 2000, he similarly distanced himself from his own Southern Baptist Convention's Jewish outreach in Chicago. As early as the 1957 New York crusade, Graham explained that his strategy did not involve recruiting people out of their religious families: “Anyone who makes a decision at our meetings is seen later and referred to a local clergyman, Protestant, Catholic, or Jewish.”

But Graham's effort on behalf of Jews wasn't just about his evangelism. When Syria and Egypt launched a surprise attack on Israel in October 1973, it soon became evident that Israel was under severe stress. The European powers refused to help. Richard Nixon hesitated to aid Israel for fear of escalating international tensions. But as the crisis grew graver, and Israel quietly threatened to use nuclear warheads, Nixon delivered weapons and supplies to stabilize Israel. Years later, Tanenbaum's widow told The New York Times that it was only after Graham personally telephoned Nixon that the airlift began.

In 1982, Graham spoke at a Russian Orthodox–sponsored conference on how religious organizations could help avert nuclear catastrophe. But he also made some side trips, including visits to the Siberian Seven—Pentecostal asylum seekers who had taken refuge in the American embassy—and to Jewish leaders at Moscow's only synagogue. Tanenbaum had urged Graham to take this controversial trip and had briefed him on the plight of Soviet Jewry. Graham always preferred to work for human rights behind the scenes and frequently used his travels in the Eastern Bloc to urge governments to allow Jews to emigrate and to teach their children Hebrew. But when he refused to criticize the Soviet government publicly, he came under attack in the press. Tanenbaum was among those who most publicly and eloquently came to Graham's defense.

As Graham's public ministry wound down, he had established a public and private profile of cordial and cooperative relations with the Jewish community. The nation was therefore shocked at what they heard in 2002, when the National Archives released 30-year-old secretly taped conversations between Nixon and Graham. The president took the lead in complaining about Jewish influence in politics and control of the media. But when he asked Graham if he believed that, the evangelist missed his Nathan-and-David opportunity to object to blatant ethnic prejudice. Instead, he agreed and added, “Not all the Jews, but a lot of the Jews are great friends of mine. They swarm around me and are friendly to me because they know that I'm friendly with Israel and so forth. But they don't know how I really feel about what they are doing to this country. And I have no power, no way to handle them, but I would stand up if under proper circumstances.”

When the tapes came out, the evangelist apologized immediately, Tanenbaum's widow defended his character in The New York Times, and the Anti-Defamation League's ever-vigilant Abraham Foxman accepted the apology on the behalf of all Jews. The controversy blew over quickly, but it left an indelible asterisk on Graham's legacy.

David Neff was editor in chief of Christianity Today from 1993 to 2012. He was also co-convener of an ongoing national Jewish-evangelical dialogue.