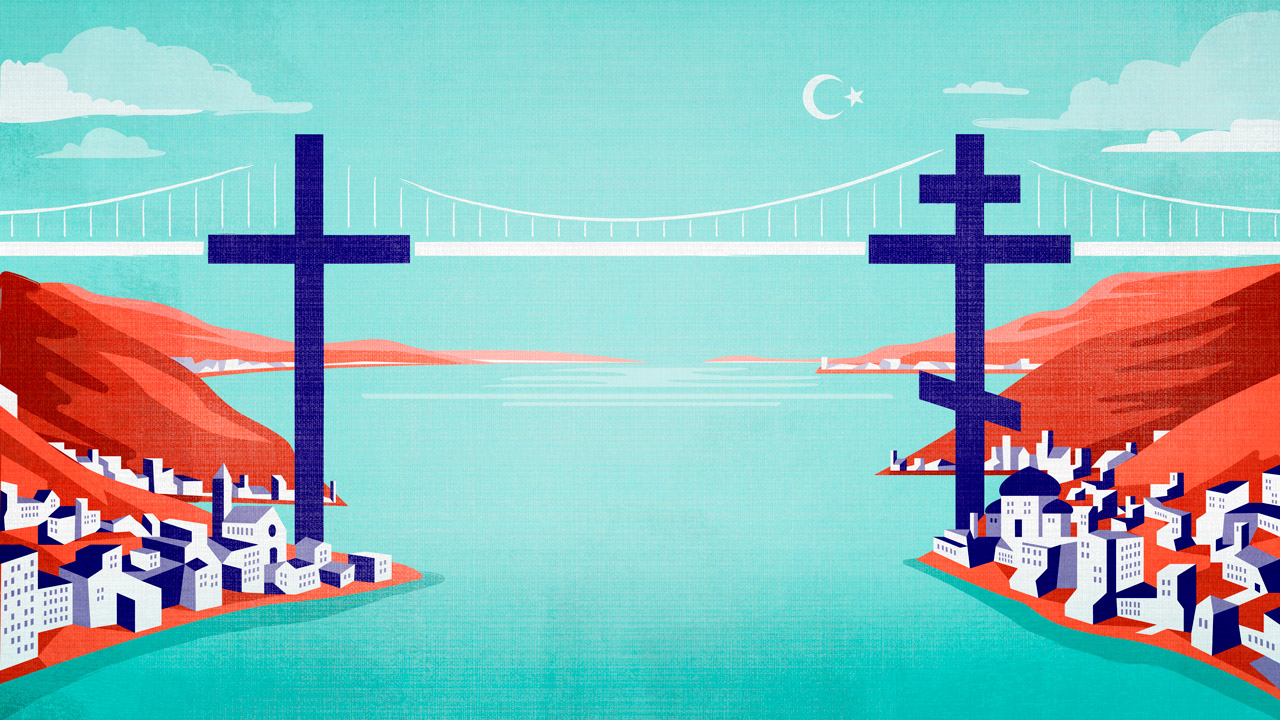

Four years ago in Istanbul, a humble Turkish book partially reversed the 11th century’s Great Schism. Catholics joined Eastern and Oriental Orthodox—alongside Protestants—to publish a slim, 12-chapter treatise on their common theological beliefs.

“You can’t find a page like this in all of church history,” said Sahak Mashalian, an Armenian Orthodox bishop and the principal scribe of Christianity: Basic Teachings. “It is akin to a miracle.”

“The biggest obstacle to the gospel is the splits and fights within Christianity,” said Thomas Schirrmacher, the World Evangelical Alliance (WEA) theology leader who spoke at the recent launch of the book in English. “[We] must prove there is one Christian message, starting between churches themselves.”

There was a “wall of enmity” separating Protestants and Orthodox in Turkey, said Behnan Konutgan, former head of the Turkish Evangelical Alliance. As the dialogue progressed, most evangelicals were “suspicious.” But about a decade ago, Konutgan and Schirrmacher began regular yearly visits with Orthodox leaders. Reconciliation was a key goal because a Turkish Protestant pastor had slandered Orthodoxy’s global head, Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew I.

Together they set up a procedure to handle such complaints. Shortly thereafter, Schirrmacher launched extensive religious liberty advocacy by the WEA for the Eastern Christian church.

“Many evangelicals are short-sighted, not realizing the Orthodox and Catholics have been here for hundreds of years,” Konutgan said. “If they read this book, they will see we believe in 90 to 95 percent of the same things.”

So whether it is nudging conservative Protestants toward Christian unity or ancient churches toward understanding evangelicals, Schirrmacher believes in the power of engagement. “Evangelicalism is the search for the DNA of Christianity,” he said. “But then other churches take it over. Suddenly it is no longer a specific evangelical conviction, but a Christian one.”

However, engagement is not always cooperative at first. For example, while early British missionaries to Egypt sought to work within the structures of the Coptic Orthodox church, American missionaries formed congregations of Coptic converts.

The church had sunk into a “degraded state,” wrote Coptic Orthodox bishop Anba Suriel of Melbourne, Australia, in his new biography, Habib Girgis, which profiles the Egyptian deacon who 100 years ago reversed the process of Coptic decline as a “light in the darkness.”

At the time, there was little education and no systematic training for Coptic priests, who for generations inherited their posts from their cleric fathers. The Protestant missionaries—who had established a seminary and a Bible society and began Sunday school services for children—provided a vital spark.

“The Copts largely resisted conversion,” Suriel wrote, “[but it] awakened in them a spirit of inquiry and an impulse to reform.”

Missionaries supplied Girgis materials, and the Bible Society of Egypt gave him free or low-cost Bibles for his students, said Sinout Shenouda, the Orthodox vice-chair of its board. “The Americans initiated the idea, and the Orthodox came to imitate,” he said. “It was competition, but useful in that it profited from the missionaries rather than just attacking them.”

Today, Egypt’s Bible Society is one of the world’s largest and no longer competes. Its board is denominationally integrated and many of its workers, who help produce more than 700 items for children alone, are Orthodox.

But engagement also provides political benefit, explains Ramez Atallah, general secretary since 1990. In Alexandria, local regulations once threatened to close down the Bible Society branch. But “national security” overrode the decision when officials realized it would deny all Egyptian Christians their Scriptures. “Evangelicals are a tiny minority in the Middle East,” Atallah said. “If the Bible Society was just for us, security wouldn’t have cared.”

Likewise in Turkey, an evangelical beginning risked being pigeonholed. SAT-7 is a Christian satellite network founded in 1995 in cooperation with Middle East churches. Turkish language coverage first beamed over the Arabic feed in 2006.

“When SAT-7 TÜRK started broadcasting, everyone was looking at us as a Protestant missionary channel,” said their local development officer. “It took a lot of time to establish and improve our relationships with the traditional churches.”

After early rejection by the government-regulated Turksat satellite, SAT-7 TÜRK executive director Melih Ekener reapplied with an extensive explanation of the channel’s aims and denominational representation. Approved in 2015, it became the first Christian station to broadcast in Turkey and now reaches over 50 million Turks.

“Everyone who accepts the Council of Nicaea is a Christian,” Ekener said. On their behalf, SAT-7 TÜRK proudly advertises Christianity: Basic Teachings.

“Western evangelicals introduced the concept of Christian media to share the faith,” said Terry Ascott, SAT-7 CEO. “But the Orthodox teach us mostly lazy evangelicals about spiritual disciplines, and how to put any crisis into the perspective of 2,000 unbroken years of church history.”

Greater engagement, embodied in the Lausanne-Orthodox Initiative in 2010, has led many evangelicals to find in this unbroken history a new vitality for their own faith. But some have gone further and become converts to Orthodoxy.

Evangelical principles seep into traditional churches. Evangelicals do too—and the cross-pollination continues.

“I don’t think it is possible to overstate the influence of evangelical converts to Orthodoxy in terms of missions,” said Alex Goodwin, annual giving director for the Orthodox Christian Mission Center (OCMC). “It has been transformative for many of us who are ‘cradle Orthodox.’ ”

The OCMC is the official missions agency for the Assembly of Canonical Orthodox Bishops of the United States. According to 2016 figures, it supports 376 local priests in 16 nations around the world, with the greatest concentrations in Kenya, Uganda, and the Congo. And out of 27 full-time missionaries working in places such as Albania, Guatemala, and Mongolia, 16 are converts.

“We have a very rich missions history,” Goodwin said. “But for a long time, there was a preservationist sense that needed to protect the heritage of the church.

“Many generations inherited this mindset. Now we are coming out of it.”

The proof? According to a 2015 denominational survey, converts tithe twice as much as cradle Orthodox. Meanwhile, 42 percent of all members said they would increase giving if their parish paid more attention to missions, evangelism, and outreach.

So whether in Turkey, Egypt, or the United States, engagement between the main branches of Christianity yields fruit. “The evangelical dream is not owned by us but is for all the churches,” Schirrmacher said. “We lose nothing when we search together for what is common to us all.”

Jayson Casper is a Cairo-based correspondent for Christianity Today.