Blue is the color of Mars at sunset. From the surface, the cold, dim light of the setting sun comes in from the horizon as it competes with the ever-present dust, thick in the air. The plains of graveled hematite that were once shades of ochre and umber by day are now jet and onyx.

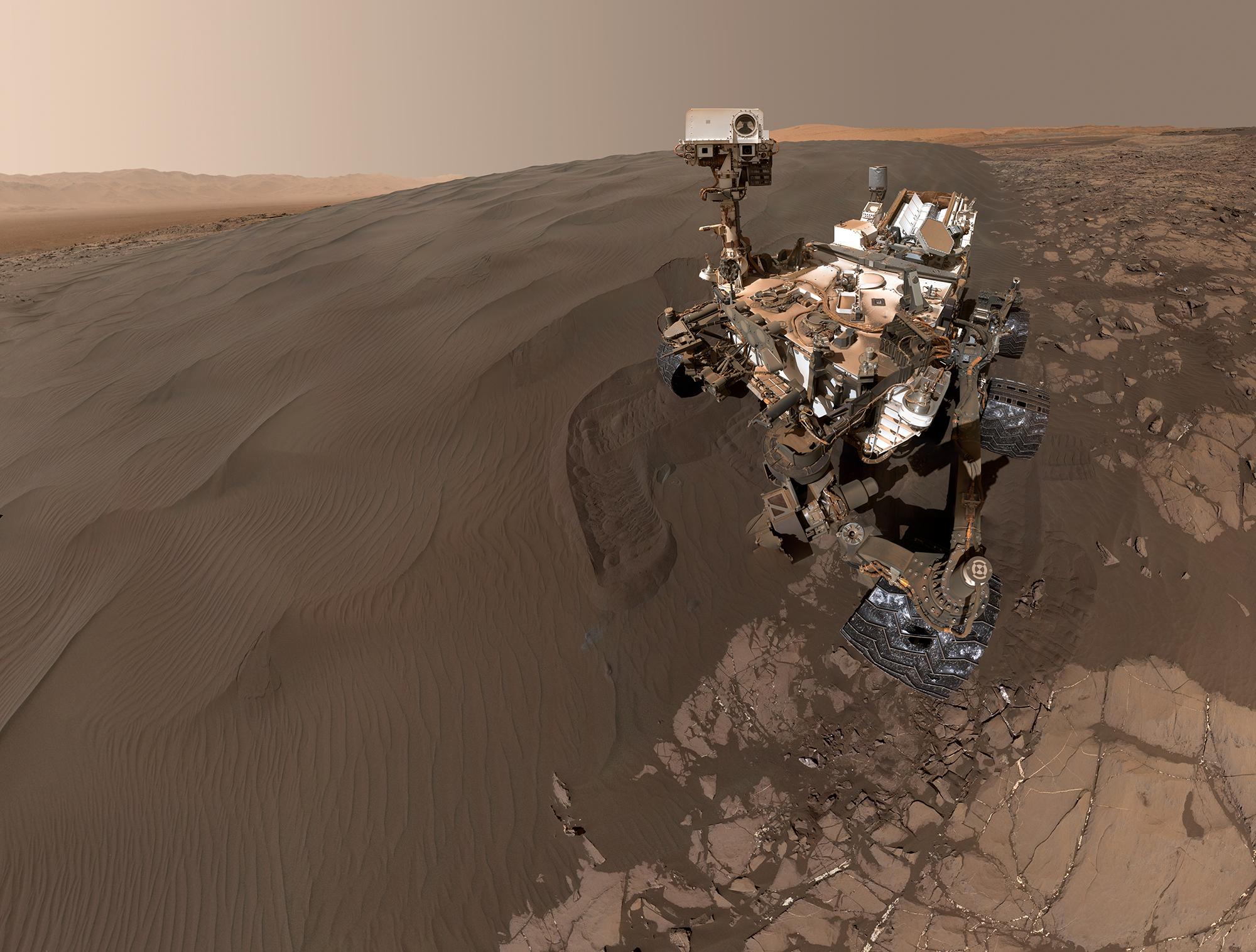

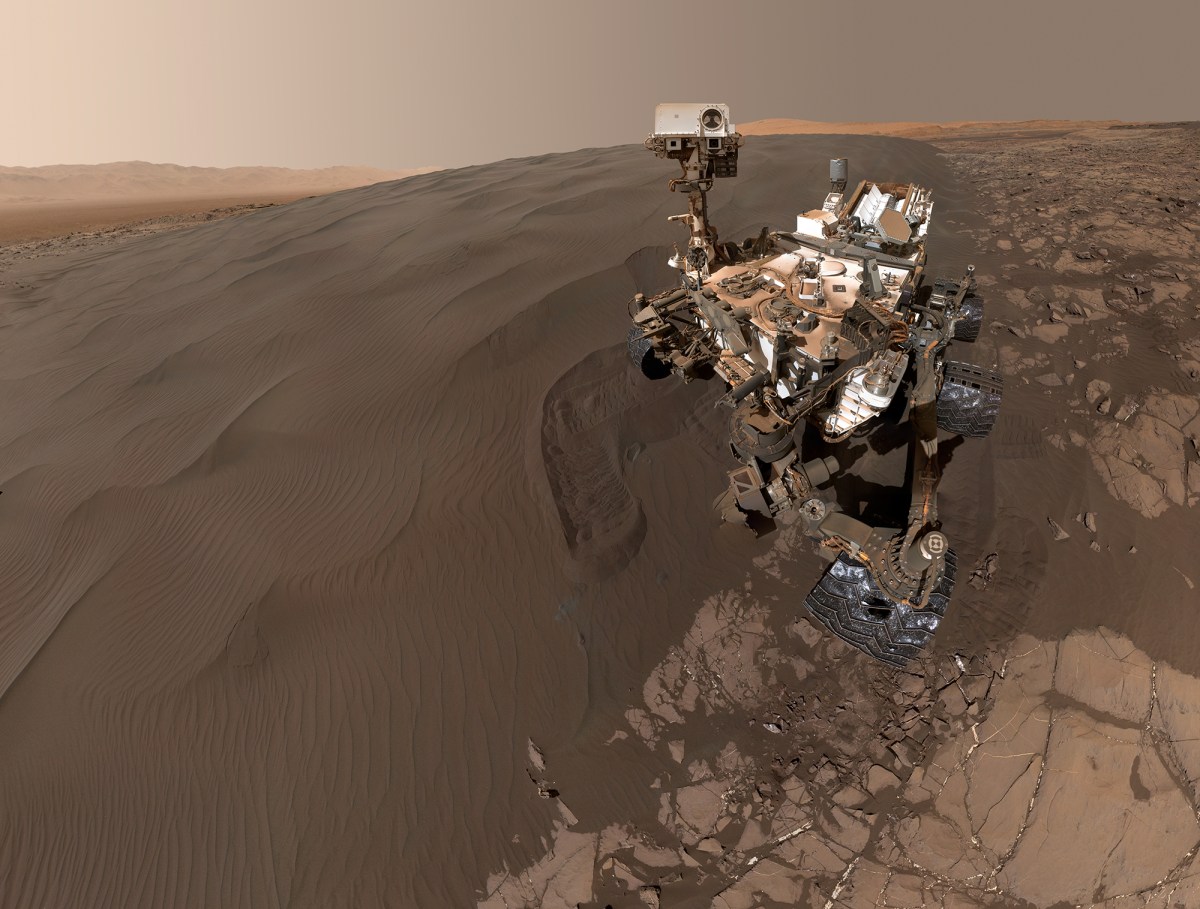

In the darkness, Mars may seem to be a dead planet. But in Gale Crater, there is human movement, as NASA’s Curiosity rover slowly treks its way up the shoulder of Mount Sharp.

Mars is not the dying planet sprung from the imagination of writers like Edgar Rice Burroughs and Ray Bradbury. Mars is more alive than ever—increasingly populated over the last two decades with the robot explorers of an emergent humanity, propelled by a sense of curiosity that infects our species.

Ecclesiastes 1:13 calls humanity’s curiosity about the universe both a “heavy burden” (in the NIV), but also a gift “given to human beings” by our Creator (in the NRSV). Everyone loves, but God calls us to a higher love. Everyone is curious, but God calls us to a higher form of curiosity.

Last month, after nearly two years of testing and repairs, the Curiosity rover is again drilling into Martian rock in its bid to discover whatever secrets may be hidden within. One of the keys to unlocking those secrets is an instrument the car-sized vehicle carries called the ChemCam, an onboard spectrometer that uses a laser to vaporize Martian rock and then, by reading light waves, can measure the rock’s chemical and mineral makeup.

“Exploring the universe around us is a very God-given activity—to follow our curiosity and to continue the work of exploring God’s creation that has [already] begun,” explains Roger Wiens, a scientist at Los Alamos National Laboratory and the principal investigator for ChemCam.

Several hundred years ago, it was Polynesian wa ‘a kaulua brimming with coconuts and Portuguese caravels laden with cloth; today, it is mechanized rovers rigged with lasers. Humans are motivated by an unquenchable curiosity—from my four-year-old son, Everett, who catches and observes snails and grasshoppers in his plastic terrarium to the 1,200 scientists and engineers completing the James Webb Space Telescope, the Hubble telescope’s successor that will allow us to see the formation and development of galaxies. We seem hard-wired to explore the big and the small of the universe around us.

Unlike the discovery of the New World, the discovery of Mars lies beyond recorded history. In the geocentric minds of the earliest astronomers, there was something different about the five wandering stars—what we today call planets—visible to the unaided eye.

NASA

NASAPyroesis (“fiery”) is the name the ancient Greek skywatchers gave to this perceptibly red planet. It was its fiery nature that caused the Babylonians to declare the red planet to be the star of Nergal (a Mesopotamian deity who was the god of death, referenced in 2 Kings 17:30), and the Greeks to follow suit and make it the star of Ares (the god of war). By the time of the Roman era, it was simply known as Mars.

In the imaginations of the ancients, Mars was a world of fire, death, and war. But we moderns are obsessed with its capacity for life.

“For me, the real wonder is that Mars was a place where living things could have inhabited sometime in the long past,” Wiens says. “We have found evidence for long-lasting lakes, probably oceans, and certainly rivers that have been there for long periods of time. These were freshwater. That means there was snow for sure, and likely rain—we don’t understand all of this, but it’s just amazing.”

Pre-Copernicus, the planets were often thought of as “worlds,” and to ancient people, “worlds” naturally assumed “life,” notes Oliver Morton in Mapping Mars. The idea that Mars could have canals and people did not seem so preposterous before the advent of flight.

Seeing worlds overhead evoked curiosity among ancient peoples. That curiosity gave shape to speculation about the “powers and principalities” that controlled those worlds, whether gods or demons.

For early Christians such as Tertullian, there was the question of what curiosity about the world—and these worlds—could teach us about God.

“Curiosity” was very popular during late antiquity, but the idea was often linked with divination, astrology, and speculative philosophy. Augustine famously separated what we today call “curiosity” into two kinds: curiositas (“frivolous speculation”) and studiositas (“principled investigation”).

In Augustine’s thinking, “frivolous speculation” is prompted by a mind seeking answers apart from God. It’s a search for new knowledge that circumvents its connection to our Creator, which results in an incomplete integration of the knowledge gained. This kind of exploration limits our ability to see the full picture. Picking up from Augustine, Karl Barth explains this kind of speculation is the root of all untruths, and John Webster likens it to a lust for new experiences.

“Frivolous speculation” is a kind of curiosity that works against God. God created a universe so vast and complex that there is no end to it, large or small, from the supermassive black hole of NGC 4889 to the submicroscopic quarks and leptons that constitute all matter. If we search for the end for the sake of the search, we will never find it; frustration will be our only reward. This is the vanity described in the warning in Ecclesiastes 8:16–17.

In contrast, “principled investigation” comes out of our fulfillment of God’s redemptive purposes for humanity. Webster explains that the “pursuit of new knowledge is natural,” meaning that it is a good and useful activity instilled in us by our Creator. Alister E. McGrath suggests it is so “that something of the wisdom of the God who made the world can be known through the world that was created.”

When our Earth was a bit younger, Adam and Eve lived a life of fruitful possibilities. But those possibilities ran out when they chose what was pleasing to their eyes over what would please their Creator. So their Creator pushed them out from that place, and Adam and Eve were forced to explore their strange, new world (Gen. 3). What must have seemed difficult to our first ancestors (Ecc. 1:13) became part of the fulfillment of God’s plan for people (Rev. 21).

Over the millennia, their progeny kept right on exploring—by land and by sea, until the whole Earth could be populated and subdued.

Mankind’s machines have been populating Mars for the last four decades, from the Soviet Mars 2 in 1971 to the latest successful landing of the Mars Science Laboratory—the Curiosity—in 2012.

NASA

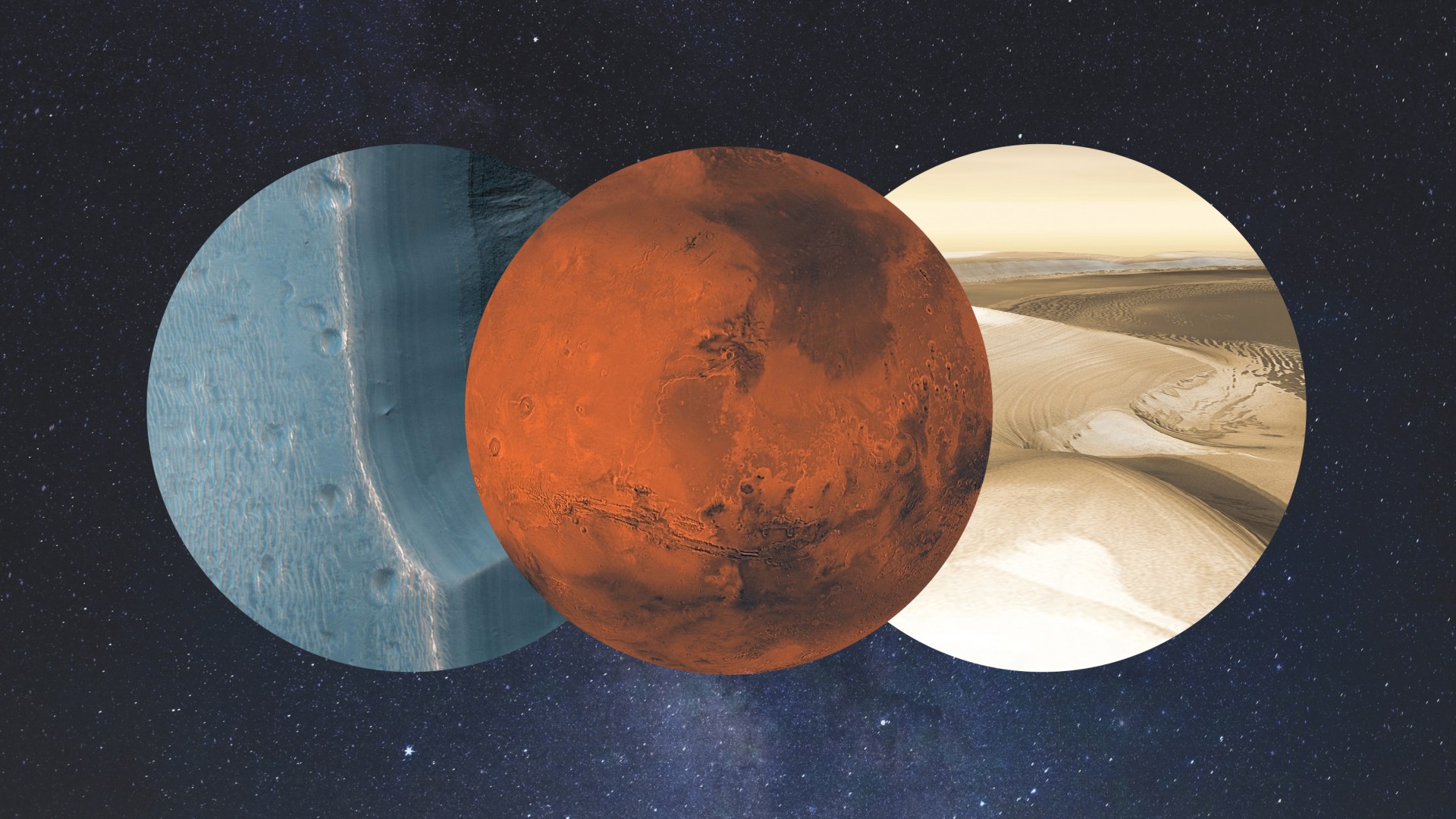

NASAMars is a world of contrasts. One recent discovery is that it still snows there—water snowflakes around the north pole but carbon dioxide snowflakes around the south pole.

Mars is one Mad Max world where there is room to rover in any direction, never stopping; around and around the planet’s surface, one can go. There are no oceans, just Martian soil and Martian rocks and Martian hills and Martian craters. From the Valles Marineris, deeply lacerated into the planet’s surface, to Olympus Mons, the volcanic Everest of our solar system, there is no escaping the possibilities.

Not all the steel that humans have flung at Mars has been successful. Contrary to popular imagination, the Babylonian wise men and the Greek mathematicians were not very successful in their star charts, either. But they tried and tried, and we continue to try, to persevere, exhaustively exploring all that God created.

Why do we explore? Is it out of frivolous speculation or principled investigation?

Due to Augustine’s, and later Aquinas’s, influences, “curiosity” became a vice by the Middle Ages, to the point that pre-modern theologians such as John Calvin denounced it. But the Middle Ages gave way to modernity and the Age of Discovery to the Enlightenment. From the rediscovery of ancient wisdom to the founding of universities to a newfound freedom of thought, there was, according to 19th- century theologian Herman Bavinck, an “awakening of the love for nature.”

“[The modern view of] nature was rather different from the workshop of demons; it was a revelation of divine glory, a theater of God’s creating and permeating power,” Bavinck writes. “And the soul [of people] experienced an awakening of deep longing for nature, an ardent desire to know and fathom it.”

Coming of age among the first generation of theologians grappling with a resurgent naturalism, Bavinck understood the challenge: For many pre-modern thinkers, special revelation was exalted at the expense of general revelation. We needed to recover a robust understanding of the creation, and to do that, we needed to explore. But we dishonor God when we explore his creation out of our own self-interest. We honor God when we explore his creation out of passion for his handiwork.

“For those of us who believe in God, we understand now that we’re a small part of this whole creation,” Wiens says. And to make the point: “We understand more about God by understanding his creation.”

The next step in understanding the Martian part of God’s creation is InSight, a stationary lander scheduled to touch down on Mars this month, whose primary goals include listening for marsquakes (seismic activity below the surface) and probing up to 16 feet below the surface. Following InSight is the Mars 2020 mission, which contains a rover outfitted with the SuperCam, an improved version of the ChemCam, with Wiens again at the investigative helm.

As Wiens points out, Mars is the only planet in our solar system that, like Earth, exists in the “Goldilocks” zone—a zone that is neither too hot nor too cold but just right for life.

From out of Eden to Eurasia to Oceania to the New World to the Moon, Mars is simply the next logical step in the continuum of human exploration. What seemed impossible in the past today is possible; what seems impossible today might be possible tomorrow. God’s creation seems now almost like his person, in that there is always so much more to explore.

“We live in a fascinating universe,” Wiens says. “It’s a big place. Where we might have thought we were the center of the universe a couple of centuries ago, we now know that there are many, many galaxies out there with billions of stars and it’s just absolutely astonishing.”

“Astonishing” is a word the psalmist might have used. He may also have agreed that the heavens declare God’s glory, and the blue dusk of Mars proclaims his handiwork (Ps. 19:1).

Douglas Estes is associate professor of New Testament and practical theology at South University—Columbia. He is the editor of Didaktikos, and his latest book is Braving the Future: Christian Faith in a World of Limitless Tech. Connect with him on Twitter @DouglasEstes.

Have something to say about this topic? Let us know here.