I’m a big fan of the Eucharist. So was John Wesley. Though you might not know it with the relative non-centrality of the sacrament in most Methodist worship services, the founder of Methodism never went more than four or five days in his adult life without celebrating the Lord’s Supper.

But Wesley never served time in a Pennsylvania prison. Before I was incarcerated, I left Methodism to join the Lutheran Church, in large part because of the weekly observation of the Eucharist. The body and blood of Christ filled me with a powerful, sustaining dose of grace that I relied on to face many life challenges. Then I arrived at a county prison four years ago for a crime I maintain I did not commit, and I lost access to Communion. There was an occasional volunteer-led Bible study, but there was no worship service. No Eucharist. And I needed the body and blood of Christ in a way I had never needed it before.

My Lutheran pastor tried repeatedly to bring Communion to me but was given the correctional runaround. He ran a gauntlet of deputy wardens, assistant deputy wardens, and acting administrative deputy assistant wardens.

He was told he could bring me Communion. Then, after driving more than an hour to the prison, he arrived and was told he could not, as our visits could only be conducted with glass between us. The next time, we got permission to meet together in a room to share Communion. But again, the elements were not permitted when he arrived.

So without Communion during my months at county, I joined my Lutheran friends in spirit. While they gathered at the table on Sunday mornings, I communed with them from a distance. I followed the liturgy from worship bulletins that my pastor had sent me. And with “wine” made from water and grape jelly, and a slice of bread from my meal tray, I joined them in sharing in the body and blood of Christ. It may seem uncouth or even foolish to join in Communion remotely, like a child having pretend tea in plastic cups, but these were vital moments of grace that preserved me in my time of desperate need.

When I moved from county to the state processing facility, I was able to attend worship, either “Protestant” or “Catholic.” I started with the Protestant worship services. In order to accommodate all varieties of Protestantism, the standard weekly worship service did not include Communion. So I was back to jelly juice and a saltine cracker (no bread—removing it from the chow hall was strictly prohibited).

As it happened, I became friends with a Catholic inmate. I told him about my yearning for Communion, and he told me to sign up for Mass and come along with him. I asked him about the church rule banning non-Catholics from the Eucharist. He smiled and put his hand on my shoulder. “This is prison,” he said. “Do you really think God cares if you steal some grace?”

Your Father, Who Sees What Is Done in Secret

The next Sunday, I was off to Mass. The liturgy was very familiar, the missal was easy to follow, and the songs in the back of the booklet contained Methodist and Lutheran hymns.We progressed through the Liturgy of the Eucharist, sitting, standing, kneeling, standing, and kneeling. I love kneeling in worship. It’s different from just sitting in a pew, like you are at some sort of performance. There’s something about getting off your butt and humbling yourself before the Almighty as you feel the discomfort of your body weight pressing down on your knees. It’s active participation in the liturgy, as you engage physically in the story of Christ’s suffering, death, and resurrection.

The priest was an older man, chubby but strong, mostly bald with his remaining gray hair barely at crewcut length. His face was a blend of sternness and compassion, heavy on the stern side. I was sure he had some sort of spiritual superpower to detect impostors among his flock of the true faith, like the Terminator or Iron Man with a scanner that labels friend or foe. When he glanced my way, I knew the warning light was glowing red, tagging me with each strain of my religious past: Presbyterian, Methodist, Lutheran, with smatterings of Baptist, Anglican, and Episcopalian.

I mentally ran through worst-case scenarios. If I went forward to receive Communion, he might throw a question at me from the catechism or ask me to name the bishop of the diocese. And when I failed to answer correctly, he would quote the relevant provisions of canon law and motion for an officer to haul me off to “the bucket,” the special housing unit where inmates are kept in high-security lockdown, to perform a 90-day act of contrition.

But then something happened. During the Invitation to Communion, he proclaimed, “Behold the Lamb of God, behold him who takes away the sins of the world. Blessed are those called to the supper of the Lamb.” To which we responded, “Lord, I am not worthy that you should enter under my roof, but only say the word and my soul shall be healed.”

And immediately I recognized this as rooted in Scripture, from one of Jesus’ teaching miracles in Matthew 8. A Roman military officer, a centurion, comes to Jesus to ask for healing for his servant, who is paralyzed and in terrible distress. Jesus, who is a Jew and a subject of the Roman Empire, offers to come and cure the man. The centurion replies, “Lord, I do not deserve to have you come under my roof. But just say the word, and my servant will be healed.”

This Roman could not be more of an outsider to Jesus and his band of Jewish disciples. And yet he is bold enough to recognize the power and authority of Jesus and to come before him humbly asking for grace. And Jesus replies, “Truly I tell you, I have not found anyone in Israel with such great faith.” Jesus answers the man’s request and heals his servant.

When I heard this Scripture incorporated in the liturgy—“Lord, I am not worthy that you should enter under my roof, but only say the word and my soul shall be healed”—I realized that while I might be the outsider, with a combination of boldness and humility I could step forward and receive this sacramental grace for the healing my soul needed.

Through Song and Sacrament

Something else that happened was the choir started to sing while people came to receive the Eucharist. The song might have been well known among Catholics, but I did not know it. The words pierced my soul:

I will come to you in the silence, I will lift you from all your fear.

You will hear my voice, I claim you as my choice, be still and know I am near.

Do not be afraid, I am with you. I have called you each by name.

Come and follow me, I will bring you home. I love you and you are mine.

The first rows of inmates were filing forward to receive the wafer, the body of Christ, with an orderliness and beauty sometimes lacking in Protestant worship, where the irregular frequency of the sacrament of Communion makes us forget how we are supposed to move from pew to altar rail and back. The song continued:

I am hope for all who are hopeless, I am eyes for those who long to see.

In the shadows of the night, I will be your light, come and rest in me.

This song was amazing! Full of grace and truth. It was as though God was speaking right to me. “I am the strength for all the despairing, healing for the ones who dwell in shame.”

And then it was time for my row. Inmates were moving toward the center aisle. I sat in the pew, trying to summon a go/no-go decision, as I heard this verse of the song:

I am the Word that leads all to freedom, I am the peace the world cannot give.

I will call your name, embracing all your pain. Stand up now, walk, and live!

I looked up toward heaven. There was no doubt. I don’t know who else was experiencing the power of that song, but I knew that God had a direct message for me: “Stand up now, walk, and live!” So I stood up and joined the procession toward the priest.

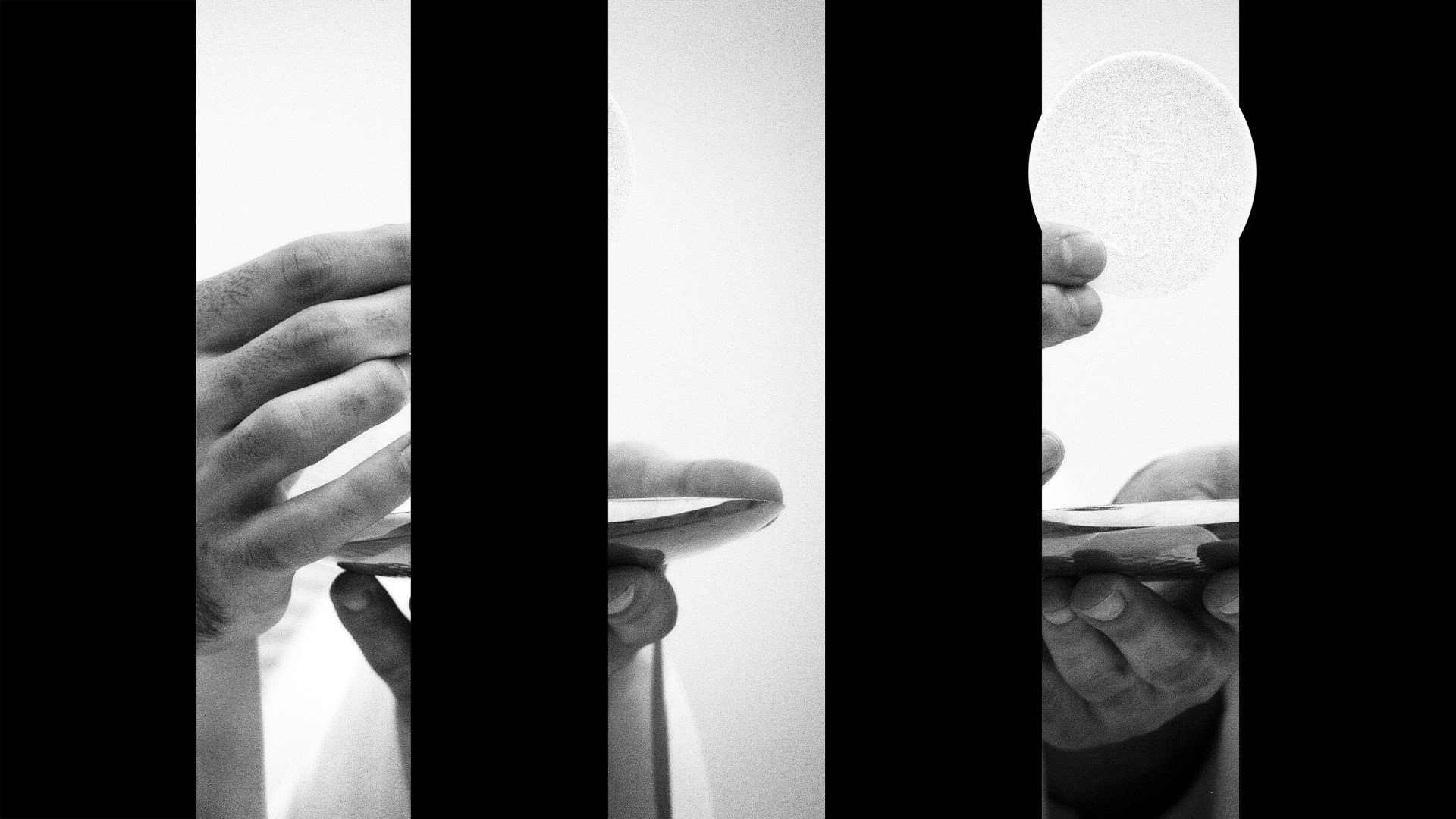

I held my hands together before me, overlapped and open to show both emptiness and the expectation of receiving something. I remembered a professor telling me once that we all come as beggars to the feast. And I truly felt like a beggar, scrounging for the body of Christ.

Once in motion, everything passed quickly and uneventfully. The priest placed the wafer in my open hands. “The body of Christ,” he said. He watched to see that I placed the wafer in my mouth. (I learned later that there had actually been incidents of inmates claiming to be Satanists taking the wafers with them for desecration.)

Back in the pew and kneeling in prayer, I got the “grace rush.” Warmth, goosebumps, some light-headedness, along with calmness and contentment. If you’ve never had a grace rush, I hope someday you do. It was simultaneously exhilarating and peaceful, the peace the world cannot give. It was what I had been longing for. It was the real presence of Jesus himself, reminding me that the words were speaking right to me:

I am the strength for all the despairing, healing for the ones who dwell in shame.

All the blind will see, the lame will all run free, and all will know my name.

Do not be afraid, I am with you. I have called you each by name.

Come and follow me, I will bring you home. I love you and you are mine.

And until God would bring me home, I knew that I was loved, and I was his.

The priest certainly understood that. I met with him shortly after that first day at Mass, and he granted me special permission to continue receiving Eucharist.

There are so many interpretations of the sacrament of Communion. We differ on the spectrum of symbol versus physical reality, who can receive, the words we use, the types of bread, wine versus juice, how the elements are served. I don’t recommend disregarding others’ beliefs on the sacraments. There are, however, three undeniable things we hold in common. Jesus said to do this. His grace is available to us in a special way when we do this. And all our human attempts at describing this holy mystery fall short. We are not worthy. But Christ still bids us all to come to the table of grace.

Lee A. Moore is a former Protestant minister and an inmate at Pennslyvania State Correctional Institution in Waynesburg, Pennslyvania. He blogs at cellvation.wordpress.com.

Have something to say about this topic? Let us know here.