“Oh, Job is so powerful!” said a man I had just met. We had found common ground discussing the congregations where we worshiped. After sharing what we did for work, I told him I had written a book on Job, and he was excited to talk to me about Job’s importance to him: “After all he suffered, Job says, ‘Though he slay me, yet will I trust him.’ ”

Others have quoted those well-beloved words to me to demonstrate that, in spite of severe losses, Job continues to trust God. A longtime friend and professional colleague once told me that what he loved about Job was that very statement. Unfortunately the common translation of that verse, Job 13:15, misrepresents Job.

I did not consider it appropriate to challenge these men in either situation, but I cringe when people cite those words from Job. They reflect a mistranslation of Job’s words that has led some to misunderstand the entire book.

Challenging long-held ideas about a well-beloved verse can make believers feel uneasy or like Scripture itself is under attack. But every Christian should want to know the truth of Scripture. Even if it disturbs us, knowing what Job says should engage us all. A careful look at the wording will show why this is important, how various Bible versions translate the text, and how this text fits into its context to give a new appreciation for the full message of Job.

Job’s Protest

Contrary to how many people remember the Book of Job, throughout most of the book, Job articulates a strong protest to God against his undeserved suffering. In chapter 3, for example, in defiance of God’s gift of life and in deep depression, Job seeks the peace of death over the suffering of his life. His speech triggers vehement responses from Job’s three wisdom colleagues. In speeches defending his innocence to them (affirmed earlier, once by the narrator and twice by God, in verses 1:1, 1:8, and 2:3), Job complains bitterly about the unfairness of his experience.

At first in reply to his colleagues, Job focuses on his miserable life and wishes God would crush him. In fact, he says, God has already begun. Weightier than the sands of the sea, Job says of his suffering, for which he holds God responsible: “The arrows of the Almighty are in me, my spirit drinks in their poison; God’s terrors are marshaled against me” (6:1–4). Job argues that it isn’t fair that he, a righteous man, should suffer catastrophic loss. He pursues God to learn the charges against him. Without just cause for such losses, God shows himself unfair.

We treasure the Book of Job, in fact, because Job protests. Without Job’s honesty, we’d lack a biblical voice for our disillusionment. Like Job’s colleagues, we often believe that if we’re faithful to God, he will protect us against misfortune. And, as a rule of thumb, that’s generally true. Psalm 91, for example, affirms this as does Deuteronomy, the historical books, and the prophets. But we also know that’s not always true. Job was written to help God’s faithful servants, in Bible times and today, as they struggle with the exceptions.

Translations of Job 13:15

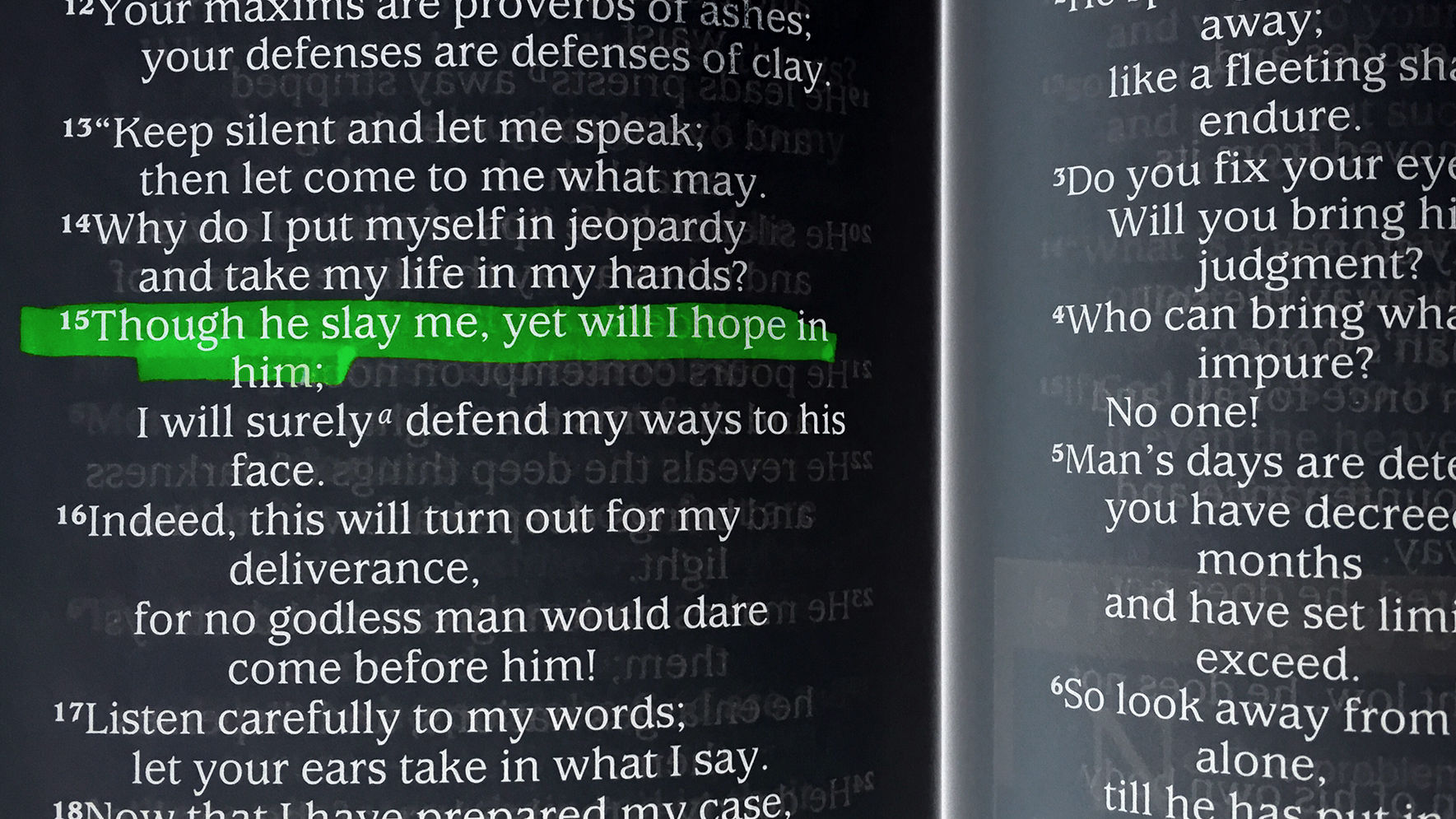

Let’s look at how some of the modern translations deal with Job 13:15. We already know the familiar King James Version (KJV) reading: “Though he slay me, yet will I trust in him: but I will maintain mine own ways before him.” The New International Version (NIV) translates, “Though he slay me, yet will I hope in him; I will surely defend my ways to his face.” This NIV rendering agrees with the KJV and with our popular remembering of Job’s words. On that same page, however, the NIV footnote reads, “Or, He will surely slay me; I have no hope—/yet I will.” Note that the footnote reads opposite of the text translation: “I will hope in him” versus “I have no hope.” How could the same Hebrew words be translated to mean the opposite of one another?

Other versions, however, choose the footnoted reading. The Revised Standard Version (RSV), for example, reads: “Behold, he will slay me; I have no hope; yet I will defend my ways to his face.” The translation published by the Jewish Publication Society of America (JPS) renders the verse, “He may well slay me; I may have no hope; Yet I will argue my case before Him.” And the New English Bible (NEB) Oxford Study Edition reads, “If he would slay me, I should not hesitate; I should still argue my case to his face.” Their study note on verse 15 reads, “An older (and traditional) translation incorrectly renders the verse as expressive of unflagging trust in God: ‘Though he slay me, I shall wait for him.’ ” Some translations translate one way, but others with the opposite meaning. How do we account for the difference? And how do we decide which is correct?

Ancient Hebrew scribes held the text of Scripture in such great esteem that even when they found what they thought was a mistake in the text, they would leave the error and make a footnote to inform the reader about what they thought was the correct reading. Describing the scribal process of hand-copying sacred manuscripts, J. Weingreen, author of A Practical Grammar for Classical Hebrew, states that “corrections of recognized errors are retained in the text . . . due to the extreme reverence felt [for the text] and acts as a safeguard against tampering with it.”

The scribes noted not only errors but also objectionable written words. If such a word conveys “an offensive or indelicate meaning,” though written in the text (in Hebrew, Kethiv), the scribes often noted that, when read aloud, it should be replaced by a euphemism (in Hebrew, Qere, a footnote). Although not a mistake, Weingreen provides an example of substituting the spoken for the written text in the divine name, YHWH. Too sacred to speak, when encountered in written text, the reader speaks “Adonai” (Lord).

How we translate Job 13:15 centers on whether we read with what is written (Kethiv), or we read with what is spoken (Qere), one of these scribal footnotes. Was the written text a “mistake” or an infelicitous, offensive, or indelicate word? The scribe may have encountered Job’s vehement protest and allowed the text to stand but added a note for the reader to say, “Though he slay me, yet will I trust in him” to avoid Job’s hopelessness. If so, that could have led some modern translators to also soften the impact of the text. As we have seen, KJV and NIV translations of Job 13:15 generally follow what is spoken. As a result, they reverse the meaning of the written text. The NEB translates hesitates instead of hope, but by retaining the not, chooses the written over the spoken.

If we’re still uncertain how to translate Job 13:15, the context can help us. Below are two versions of 13:13–15. The first translation follows the spoken, the second the written.

Spoken:

Be silent before me so that I may speak;

Then let come on me what may.

Why should I take my flesh in my teeth and put my life in my hands?

Though He slay me, I will hope in Him.

Nevertheless I will argue my ways before Him (NASB).

Written:

Keep quiet; I will have my say;

Let what may come upon me.

How long! I will take my flesh in my teeth;

I will take my life in my hands.

He may well slay me; I may have no hope;

Yet I will argue my case before Him (JPS).

Which translation better fits the context? I believe it’s the JPS. Job silences his colleagues, determines to take his life into his own hands by daring to bring (legal) charges (“my case”) against the Almighty. Anticipating the sentence of death for his challenge—for no one can see God’s face and live (Ex. 33:20)—Job acknowledges God may well slay him and that he may have no hope. He determines, nevertheless, to pursue his case to God face-to-face.

Choosing the positive nuance of “hope” or “trust,” as some English translators do, introduces an idea alien to the flow of Job’s argument. In fact, the written Hebrew text states, “I have no hope!” Most evangelical commentaries support this reading. Gerald Wilson, for example, in the New International Biblical Commentary volume on Job, discusses both readings, after which he concludes: “Rather than expressing monumental faith, Job is instead indicating just how hopeless his circumstances really are.” David J. A. Clines, who wrote a three-volume commentary on Job in the Word Biblical Commentary series, states, “The traditional translation of AV [Authorized Version], ‘Though he slay me, yet will I trust in him,’ must regretfully be set aside as out of harmony with the context.” In his determination to confront the Almighty with the injustice of his suffering, therefore, Job accepts the risk of death.

Job’s Message

How does translating 13:15 “He will surely slay me; I have no hope” fit the context of the book as a whole? In chapters 4–27 of Job, he gradually develops a lawsuit to arraign the God of justice over his unjust suffering. Then, in chapters 29–31, Job presents his defense to the Almighty. After Elihu speaks, God finally responds, confronting Job with his awesome presence and unleashing a barrage of unanswerable questions (chapters 38–40).

Now seeing his case from God’s perspective, Job silences himself (40:4). He then must withstand God’s withering critique: “Would you discredit my justice? Would you condemn me to justify yourself?” (40:8). Job finally acknowledges God as master of all creation, including humanly uncontrollable chaos (the “Behemoth,” or “Leviathan,” mentioned in chapters 40–41). After Job acknowledges his ignorance of God’s perspective, he withdraws his case (42:1–6).

Throughout Job’s struggle, God’s absence frustrates him (23:3–9). Yet God waits patiently before responding. And, although God’s answer was not what Job expected, God demonstrates respect for his servant: He honors Job with his presence, he speaks personally to him (38:1; 40:1), and he hears Job’s complaint (40:2). God, in fact, later commends Job for his honest words. “I am angry with you [Eliphaz] and your two friends, for you have not spoken of me what is right, as my servant Job has” (42:7).

Misreading Job 13:15, therefore, involves more than an academic dispute. It minimizes Job’s anguish and lessens his fierce determination to bring his case to God. It hinders us from expressing the anguish we feel when confronted by hardship and tragedy. As a result, it reduces the power of the book to help the sufferer. Job’s words give us voice when we suffer intensely, yet dare not express how we feel. If Job protests what appears as injustice from God, whom he trusts to be just, should we hold back our tears, cries, or grief over our tragedies? Can we not, like Job, worship God both as master of creation and as the one to whom we can express our deepest hurts?

Gordon Grose, a Baptist minister, spent 25 years in parish ministry before becoming a counselor and writer. He is the author of Tragedy Transformed: How Job’s Recovery Can Provide Hope for Yours (BelieversPress, 2015).

Have something to say about this topic? Let us know here.