Among the many plans for the 30th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall, the augmented reality MauAR app offers users a glimpse into both the sudden and gradual accretions of that sprawling built environment of political control over the 28 contentious years it stood (1961-1989). Through the application’s lens, the Wall rises again, along with guard towers, barbed wire, and the raked sand of the death strip. For a forgetful world, it provides a sobering virtual glimpse into what life was like.

Far harder to see are the moral forms of control built up by the German Democratic Republic (GDR) in the four decades during which the communist regime held power. In a timely way, Elisabeth Braw’s God’s Spies: The Stasi’s Cold War Espionage Campaign Inside the Church, searches this more hidden dimension. A former journalist and now director of the Modern Deterrence project at RUSI, a London-based defense and security think tank, Braw analyzes why so many East German pastors, bishops, and theologians worked as Stasi unofficial collaborators (Inoffizieller Mitarbeiter, or IMs).

From ground-breaking interviews and careful record-combing, Braw offers up new material for students of the GDR era. But she also treads soberly upon the old, familiar, yet easily forgotten paths of the mealy moral middle of human beings in systems that reward duplicity and corruption.

The Price of Betrayal

The Stasi, East Germany’s Ministry for State Security (or MfS), existed to protect the regime, securing and consolidating power through godlike knowledge, and ever-alert for signs of subversion. Of course, the only way to achieve that kind of atmospheric knowing—that pervasive and intimate level of surveillance—was through ordinary people everywhere snooping on almost everyone else. What drives people, even clergy, to such widespread human betrayal is the puzzle at the heart of Braw’s study.

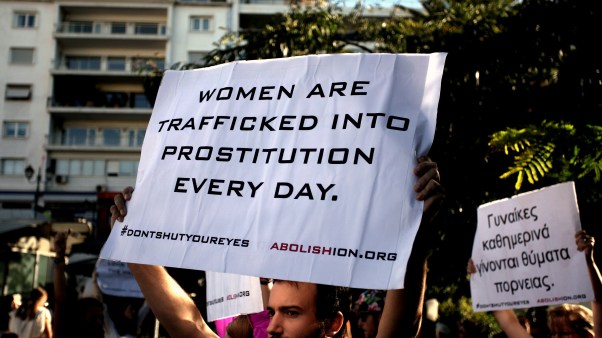

In a landscape of repression, as Braw observes, the church was “East Germany’s only semi-free space,” the only area where one could get some distance from the regime’s omnipresence. Churches drew in the “opposition-minded” as well as the religious. It seemed to be a space beyond the government’s godlike gaze and grip.

But it was not. The potential threat that the churches posed to the regime necessitated their infiltration and monitoring. Enter Department XX/4, the Stasi’s ecclesiastical office, and its extensive web of unofficial agents (IMs). Braw’s book recounts shocking levels of cooperation within the church, just as there was outside of the church. One small example: Two-thirds of the professors in Humboldt University’s theology department worked as IMs. A not-insignificant number of students did too. No matter where they were, East Germans assumed that someone was always listening and reporting.

While there have been and still are more physically brutal regimes than the GDR, the Stasi’s skill at preying on human corruptibility in its brief yet powerful tenure continues to command attention. “Like any good espionage novel,” Braw writes, “the story of the Stasi’s pastor spies involves betrayal, career advancement, even sex.” Her book reveals an assortment of pathetic details, including how pastors were willing to spy and surrender information on others in exchange for things like lamps and cigars.

The East German method often relied on a softer approach, catching more flies with honey than with vinegar. Recruitment, Braw observes, was achieved with “some porcelain, some stollen [a German sweet bread], and a friendly Christmas visit.” Once in the net, IMs offered up reports which their handlers passed to the department. Handlers offered agents something too, sometimes merely a listening ear into which IMs could air their personal grievances and play out possible vendettas. IMs often sought and found beyond-the-bureaucracy solutions for the degradations and inconveniences of life under Communism. A few betrayed information out of ideological purity, but most had a price.

Throughout the book, Braw introduces key IMs, detailing their exploits, their ambitions, and the effects of their compromises. She weaves their fascinating and, at times, plodding stories together, and the name changes can make the narrative challenging to follow. But mercifully her book features lists of abbreviations and agents and their code names. Eventually, the characters take on flesh.

Certain key figures prove critical to her account. Among them, Colonel Joachim Wiegand stands out. As head of the Stasi’s Department XX/4, Wiegand sat for many interviews with Braw, even inviting her into his home. Curiously, though willing to reveal much, he refused to divulge information about any living Stasi agents. For a man who built his career on testing and exploiting human weaknesses, Wiegand’s commitment to his own code of honor fascinates Braw, as do his worldly insights on human nature.

Braw also interviews Jürgen Kapiske (code name: IM Walter), one of the few pastor agents willing to talk with her. Now exposed and defrocked, Kapiske worked as a Stasi agent out of a sense of duty to his country, swiftly gaining a strong reputation. But Braw discovers how some aspects of his memory fail to match her research. She writes that former IMs are not allowed to read their own files, which were opened to the public in late 1991, denying them access to the knowledge they once helped to collect. Moreover, the Stasi eventually recruited Kapiske’s wife (now ex-wife), a fact that Kapiske did not seem to know when Braw raised it.

Braw’s insights into these complicit individuals during her fact-finding missions add poignancy to her research. She credits Wiegand, Kapiske, and others for helping her peer into a historical and moral abyss. These narrators fill a moral knowledge gap in the midst of the mountains of records and files, since, as Braw notes, “the world knows very little of how the Stasi’s officers operated, how they thought, what motivated them.” Besides the petty compensations, Braw notes that some IMs found “clandestine action and gaining power over innocent people . . . an addiction.” She manages to honor the complicated humanity of these figures without losing her wits. In doing so, she also demonstrates the worth of wrestling with history without clear heroes.

The Truth Exposed

That ambiguous terrain emerges clearly in her chapters on Bible- and literature-smuggling. Many, like me, who grew up in American churches during the latter years of the Cold War heard heroic stories of Bible-smuggling. We pitied those behind the Iron Curtain, rightly mourning their lack of religious, political, and intellectual freedom. But in Braw’s account, it’s clear that smuggling groups, along with their Western financial supporters, were susceptible to forms of moral ignorance as well. The deeper that IM agents penetrated into smuggling routes, the more Bibles and literature the Stasi and KGB collected into storage. Western organizations reported these unknown losses as proof of success to donors eager to pledge more. Without facile equivocation, Braw demonstrates how the work of knowing and not knowing always comes with moral complications.

Yet in making soul-shackling deals with the Stasi, the IMs were also played for fools. As Braw shows, they too believed in the Stasi’s godlike nature and naively assumed that both the GDR’s future and their own were secure. To illustrate this point, she introduces the “frustrated spy,” Aleksander Radler (code name: IM Thomas), who was desperate to secure a university position back in East Germany from his Stasi-imposed exile in Sweden.

But the godlike have limits, and can die sudden deaths. Despite its awesome power, the Stasi failed to anticipate the upheaval that came in 1989. When the regime collapsed, more of the truth came out. Exposed, the church that proved midwife to the 1989 revolution was also revealed to be complicit and, sadly, more reluctant than other civic institutions to deal in those plain facts. In a landscape of lies and willfully obscured truths, sifting facts and writing a more truthful account of history is difficult but also critical to the faithful work of remembrance. Braw’s work helps us see and remember more truthfully.

“It was all futile,” Wiegand told her in one of their interviews. But through Braw’s lens, we see that his assessment is far from accurate. Besides giving political protection to an increasingly fragile and evil regime, Department XX/4 managed to salt the spiritual earth with the church’s help. Yet Braw reports that as his department was shuttered in 1990, this same atheistic Stasi official arranged to have 30,000 confiscated Bibles still languishing in the department’s basement shipped to the then-Soviet Union. He told her it felt wrong to destroy them.

The mysterious terrain of the human heart persists, no matter how hard we look.

Laura M. Fabrycky is an American writer and spouse to a U.S. Foreign Service officer. She lived in Berlin with her family from 2016-2019, and now resides in Brussels. Her book, Keys to Bonhoeffer’s Haus: Exploring the World and Wisdom of Dietrich Bonhoeffer (Fortress Press), releases in March 2020.