Every election cycle, women’s issues are a flashpoint in the public square. This year is no exception: Candidates on both sides are debating abortion, equal pay, family leave, and maternal mortality.

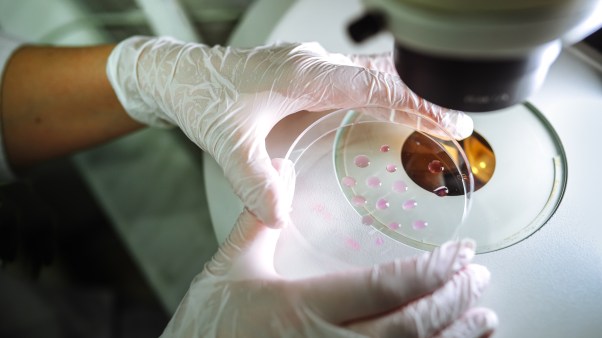

These political clashes often hinge on deeply held views about who women are, how they’re wired, and what they need. One of the most salient aspects of female identity is our maternal nature—the inclination (broadly speaking) to foster enduring ties with our offspring. Gender essentialism is fraught with land mines and dangerous generalities, and not all women experience the maternal pull. Nonetheless, most of us would agree that women’s biology is in fact distinctive, and the innate potential to bear children and bond with them not only carries great weight for the family but also shapes our commonwealth.

The political Left and Right mishandle these maternal instincts in different ways. For hard-line progressives, female “nature” is a social construct to embrace or escape—it doesn’t serve a normative purpose. We see this view play out legislatively. Liberal Democrats rightly pride themselves on defending family-friendly policies. But they concurrently promote pro-abortion policies that treat a woman’s bond with her child as entirely voluntary and even arbitrary—severed here, supported there. “To Planned Parenthood, an undesired life is no life at all,” writes Russell Moore in National Review.

Those on the Right have a nearly inverse enigma. Both center-right and far-right Republicans tend to value a woman’s distinct maternal nature and the children who come with it. But that helping hand comes up short in other arenas, as mothers are too often left to fend for themselves by conservative politicians and corporate heads who use family-friendly rhetoric but fail to support family-friendly policies and practices.

Although moderate Republicans are finally paying attention to the frequently debated family leave issue, they have a history of dismissing it. “Studies have confirmed the [economic] importance of stable families,” writes Abby McCloskey in National Review. “This creates an interesting challenge for Republicans, given their emphasis on increasing economic opportunity: How can a party that remains tentative about family policy get ahead of the curve?”

Irrespective of one’s politics, it’s fair to say that both sides to one degree or another have enabled what New York Times columnist Ross Douthat calls a “more atomized, fragmented, and post-familial society.” That’s the bad news. The good news is that Christians can turn to biblical anthropology for guidance. As believers who affirm God’s design of male and female, we reject the idea that a mother can “forget the baby at her breast” or in her womb (Is. 49:15) and simply opt out of biological bonds through abortion. We also reject the idea that motherhood is relegated to the lonely living rooms and daycare centers of America, unsupported by the collective village of family, community, government (Rom. 13:1–6), and, in particular, church.

As the body of Christ, our vision is fourfold. We celebrate the fact that God made women in his image (Gen. 1:27) and gave them a unique telos that manifests itself in diverse ways. We point to motherhood as part of that telos and praise the innate virtue of maternal care. We invite the entire church— adopted uncles and aunts, single friends and godparents—to join mothers (and fathers) in raising children to follow Christ (Matt. 18:3–6). And finally, we laud this high calling for how it forms our culture and the kingdom beyond it.

Although this Christian vision doesn’t map cleanly onto the political landscape, it does underscore a sociological truth: Mothers across the globe are imbued with the extraordinary potential to nurture crucial bonds with their kin, and the degree to which we affirm that motherhood is the degree to which our families and communities thrive.

In this election season, Christian leaders and legislators are faced once again with hard questions. How, exactly, do we pursue family leave legislation, flex-work policies, pro-life laws, pro-life practices, and village values? And how do we consistently implement these policies and practices in the church, home, office, and public sphere? The solutions are often labyrinthine—there’s no way around that. But any progress we make is largely contingent on our willingness to view maternal nature not as something to escape, erase, or ignore but as an essential foundation to our social and political health.

Andrea Palpant Dilley is senior associate editor at CT.