Caleb Ofori-Boateng, a 39-year-old Ghanaian herpetologist, laughs at the idea that he might be a modern-day Noah.

But his life’s purpose has something in common with the famous figure from the Book of Genesis.

Take the new species of small, brown, pop-eyed frog with tiny teeth and a shrill voice that he and some colleagues just described in a scientific journal.

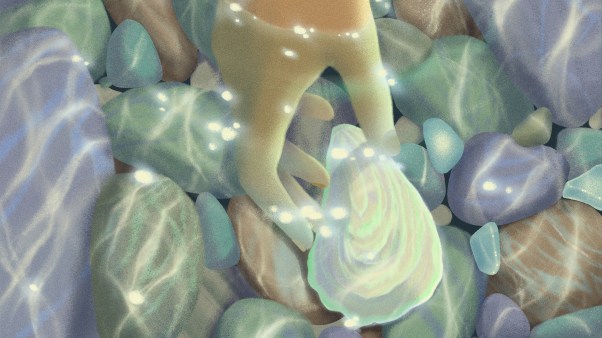

The entire population of the Atewa slippery frog is thought to live in just five clear-running streams in Atewa, a wildlife-rich evergreen forest on a mountain range north of the Ghanaian capital Accra.

But the area is threatened by government-backed plans to mine for bauxite, used to make aluminum. Should they go ahead, mining will likely destroy the forest and kill off the frogs.

Ofori-Boateng and his colleagues at Herp Conservation Ghana, a group he founded, plan to remove some of the frogs and breed them in captivity—in an “amphibian ark”—until it’s safe for them to return to their natural habitat.

“I feel that God is in what I do. And saving species is a godly thing to do,” he said.

Saving species, especially frogs, is what Ofori-Boateng has been doing for the past 15 years, with the support of the church and a strategy he calls “conservation evangelism.” It started among communities near the Atewa Forest.

As a new science graduate and the country’s first locally trained herpetologist working in Atewa in 2006, Ofori-Boateng yearned to share his experiences and discoveries with communities living at the foot of the hills. With no funds to organize meetings, and as a Christian himself, he turned to the churches.

Ofori-Boateng was not a public speaker, but he trusted God would help him. He made a commitment to Christ at the age of 12, five years after his father, a gamekeeper who loved his family, had died. Life was hard—even getting food was difficult—as his mother tried to raise eight children alone. But they trusted God.

“The only thing that kept me was my faith in the Lord Jesus. I was always on my knees, just waiting on him, seeking his help, seeking his assistance,” Ofori-Boateng recalled.

Speaking in public, he relied on that same help. He knew his message was hitting home when a woman at a Pentecostal church came to him and confessed to killing a frog the previous evening. Ofori-Boateng told her she didn’t need to feel bad, but she could stop killing frogs.

“I’m personally convicted,” he said. “I pass on this conviction. And the reference is there, which is the Bible that we all believe in. It’s a conviction that leads to action.”

That action may save frogs, and with it the forest. According to A Rocha Ghana, the local branch of the network of Christian conservation groups, the mountain range supplies water to more than five million people and is home to frogs, spiders, trees, and butterflies found nowhere else in the world.

In addition to the Atewa slippery frog, Ofori-Boateng found another new species of frog. He got to name it after his mother, Afia Birago. The Afia Birago puddle frog was the reason the Atewa Forest was added this year to a list of more than 850 sites the Virginia-based Alliance for Zero Extinction is working to protect. Designations like this raise Atewa’s profile and make it harder for the government to pursue its mining plans, conservationists say.

Big mining ventures aren’t the only threats to Atewa. Hunting, logging, farming, and small-scale gold mining have also taken their toll. Christian conservationists try to help people see the land as something more than profit.

“Where a forest may be seen as simply a source of firewood to start with, biblical truth helps people to see the forest as something to be cared for to the glory of God,” said Murray Tessendorf, director of A Rocha South Africa. “Now it’s cared for in a manner that protects the forest and makes its use sustainable.”

Traditionally in Ghana, village elders and leaders protected nature, albeit through fear, Ofori-Boateng explained.There were prohibitions against fishing in some rivers, cutting down certain trees, or farming close to water, because of the local deities.

Christianity and Islam took away the fear. Only around 5 percent of Ghanaians now subscribe to animism, according to a 2010 census. About 71 percent of Ghanaians are Christian, and 18 percent are Muslim.

“People now believe in a supreme God, and so they are no longer afraid to go into the forest,” Ofori-Boateng said.

This has inadvertently led to abuses against the environment. But it has also led to a powerful opportunity to change attitudes.

Since it began in the village of Sagyimase at the foot of the hills in 2006, conservation evangelism has achieved some dramatic results. In the Volta region, about 120 miles from Atewa, near the Togo border, Ofori-Boateng helped convince the community and local churches to donate land to conservation.

Initially, communities there were unwelcoming. They liked to eat the Togo slippery frog, even though it was endangered, and did not like the idea of giving up land. But by working with local churches, the conservation evangelists managed to convince the community, including the Evangelical Presbyterian Church, to donate around 500 acres of land toward conservation.

“Frogs are important flagships,” Ofori-Boateng said. “If you can convince people to save a frog species, then you’ve already convinced them to save everything.”

Such radical changes in mindset wrought by faith-based conservation have been noticed elsewhere. Tessendorf points to the Indian state of Nagaland, where church-led interventions helped convince local communities to stop slaughtering tens of thousands of Amur falcons during their epic annual migration to Africa.

Beyond the local communities, there are also signs the world is taking notice.

In February, conservation group BirdLife International and others helped convince three global manufacturers—BMW Group, Tetra Pak, and Schüco International—not to use resources taken from Atewa because of the environmental impact of mining.

A Rocha is advocating the whole area be designated a national park.

These efforts have not stopped government plans for major mining operations, however, so Ofori-Boateng is building an ark for the frogs and talking to churches about the need to save them. He believes hope for protecting the forest still lies in the power of people.

“What I am looking at is a united people, people filled with one purpose,” he said.

Pria Ghosh, a program officer with Synchronicity Earth, a London-based conservation charity that partners with Ofori-Boateng’s group, agrees.

“What Herp Conservation Ghana does is empower people and organizations to express themselves, to be heard, and to find the like-minded communities and solidarity necessary to stand up for places like Atewa,” she told CT. “They are making the world listen.”

Ryan Truscott is a journalist in Zimbabwe.