It was nearly noon in Chengdu, and the early June day had begun to heat up. Several Christians from Early Rain Covenant Church stood in front of a gynecological hospital, handing out pamphlets to people walking past.

The Chinese pro-life activists had gathered for Children’s Day (June 1) and were asking women to refrain from getting an abortion that day. Their pastor, Wang Yi, was supposed to join them. But early on that 2013 morning, police officers had blocked him from leaving his house.

From 2012 to 2016, members of the well-known Reformed congregation took to the streets of Sichuan’s capital on Children’s Day to advocate against abortion. Throughout the year, the church organized anti-abortion public lectures. But activists frequently faced government pushback; police often blocked speakers from leaving their homes or broke into the venue to halt events.

By 2016, the crackdowns seemed to have worked; the anti-abortion event publicity disappeared from WeChat. At the end of 2018, Wang was arrested and jailed and the government banned Early Rain from gathering.

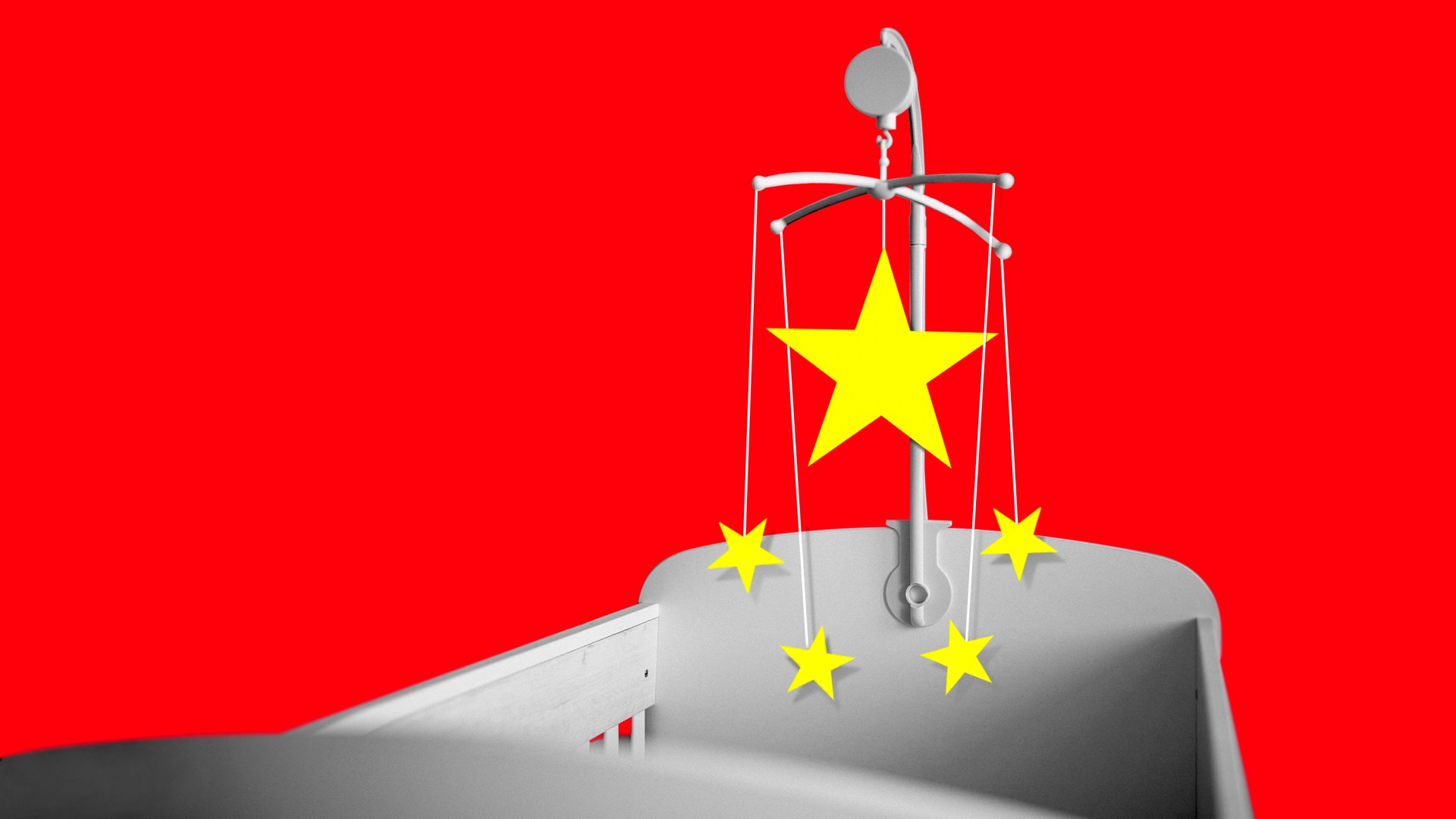

But the government had also changed its tune on abortion. After decades of China pushing its one-child policy, the reality of a low birth rate led to policies encouraging families to have two or three children.

Today, the disbanding of Early Rain and the government’s pivot on abortion have led pro-life Chinese Christians to reflect on the best strategies to protect unborn babies and take care of pregnant women. Though disagreements exist over how this congregation and the greater church have organized around fighting abortion, Early Rain’s courage in proclaiming a pro-life message impressed many in the wider Christian community.

“Most Chinese people, including Christians, lack a basic understanding of life and God’s sovereignty over it,” said Ruth Lu, who returned to Shenzhen after finishing her graduate studies overseas. (With the exception of Wang, Christians in China quoted in this piece have been given pseudonyms for their own safety.)

“The voice that upholds life is precious when most people are used to giving up on life so easily,” Lu added. “It is especially precious because public Christian witness like that of the Christians in Chengdu is a rare occurrence.”

‘A wonderful witness to the gospel’

Early Rain made its case for its pro-life values on theological grounds. Every human being’s “life is made by God and belongs to Him,” says an anti-abortion statement written by Wang. Consequently, “no one has the right to murder God’s creation.” A fetus is a human being from conception, it adds; therefore, the commandment “thou shalt not kill” means “thou shall not abort” when it is applied to the issue of abortion.

Chinese Christians widely agreed with Early Rain on these points. While overseas reports often only highlighted Yi’s church, activities such as the distribution of the anti-abortion pamphlet were an interdenominational ministry that many other churches participated in as well, said Xiao Yu, a Chengdu resident who works for a ministry that helps pregnant women and mothers.

“In the reality of China, such ministry is a wonderful witness to the gospel and one of the significant missions God has given to Christians in China,” she said. “Over the years, this ministry has continued, albeit in a small way. It has saved the lives of many fetuses, and some who have had abortions have heard the gospel and even been baptized.”

Early Rain’s pamphlet also included four demands of the municipal government, hospitals, and Chengdu residents:

- Abortion advertisements should be banned outdoors, in the media, in schools, and on buses.

- Abortions by minors should require the consent of both parents.

- Hospitals should inform those seeking abortions of the alternatives to abortion and all the possible dangers of abortion.

- No abortions should be performed on Children’s Day.

Some Christians, however, questioned the efficacy of these demands, as well as Early Rain’s activism practices.

“I admire the brothers and sisters of the Early Rain for their actions in difficult circumstances defending the values of their faith, but I do not necessarily agree with the strategy,” said Shaolong Jiang, who pastors a Mandarin congregation in Chicago. “When a young woman who is already thinking about abortion receives an anti-abortion booklet by the road, the conversation about abortion already happens too late.”

In the numerous conversations Jiang has had with women about abortion, he’s often wished the church was more proactive on this issue. He says his time in the US has shown him the need for a holistic strategy for pro-life activism.

“In the United States, the church has made many efforts to legislate against abortion, but can the church really support women who lack the social resources to have their children?” he said. “Where is the church when these women are facing all the hardships and despair that they need to go through in raising their children alone? What can we do for them?”

While the church in China encourages Christians not to have abortions, it seems to lack the commitment to take on the responsibility of raising the child together, says Hu Yue, who pastors a church in Shanghai. Instead of letting individual families face the consequences of not having an abortion, the church should “let the child be born and then raise it together” with the family.

“[Chinese Christians’] anti-abortion promotion may have overplayed the impact of the government policy, emphasizing systemic sin at the expense of downplaying individual sin,” he said. “Creating the illusion that the official family planning policies are evil and individual abortion is because the woman has no choice.”

A new form of family planning

The Chinese government’s policy change from only one child to actively encouraging and incentivizing couples to have babies presents a new and different challenge to the Christian pro-life witness.

Last August, the Chinese government passed a law officially allowing families to have up to three children. The shift comes as the country’s population grows increasingly old and exits the labor force. But this new “freedom” is unlikely to change many minds; the expense of raising a child and a lack of confidence in marriage leave many young people disinterested in having a family, says Lu.

“What Christians advocate for marriage and childbirth has accidentally become conforming to the policies advocated by the government,” she said. “This, in turn, has ironically led some young people who resent the policy of encouraging childbirth to become resistant to Christian values.”

China’s family planning policies have never held to consistent moral values, says Jiang, pointing to the government’s wild policy swings. Instead, many of these decisions have been made with politics or economics in mind.

Chinese people, including Christians, have generally accepted the presupposition that the government has the right to regulate fertility, says Shi Ming, a house church pastor, who believes that believers should reconsider this position.

Indeed, as Hu points out, policies that encourage more children are also a form of family planning.

Regardless of future government policy, the church has a responsibility to care for those most affected by it.

Recently, during a public chat on the app Clubhouse, a young woman who had chosen to have an abortion asked Jiang what the church could do for her and for women like her.

“As a pastor of a church, my faith and my calling require that I cannot support your choice of abortion or anyone else’s,” Jiang said. “But even if I don’t support abortion, that doesn’t mean our church won’t come alongside women. If you are in my church, we will be there for you to the end.”