Brad Hendrickson had a flat tire, and his jack wasn’t up to the task. Flat tires are frustrating in the best of times. This was not the best.

He was in eastern Ukraine, in the besieged city of Bakhmut, and the flat left him exposed some 500 meters from Russian troops. He started searching nearby blown-out cars, looking for a jack he could use, but the pace and intensity of shelling, which sometimes spit debris on him, forced him and a companion back. He returned a few hours later.

Bakhmut is a city of close calls. For months it has been one of the most active areas of fighting in Ukraine, with incessant shelling and trench warfare reminiscent of the fighting in World War I. Thousands of soldiers have died, and many civilians too. Volunteers have been killed.

Hendrickson is a noncombatant volunteer. Over 3,000 Americans contacted the Ukrainian embassy about volunteering. Hendrickson is one of the ones who followed through.

A burly man with a big beard and a tendency to lace his fingers together while he talks, Hendrickson doesn’t look out of place in Ukraine until he says hello out of the window of his 20-year-old Toyota Land Cruiser. The accent gives him away—American. The 43-year-old used to be a luthier in the Twin Cities before moving to Maine. For a while he drove a UPS truck. He’s been in Ukraine since the early weeks of the war.

He can explain why he’s here. But it’s not simple.

“In a way, that answer is a 40-something-year, sprawling answer,” he told CT.

It has something to do with history. Something to do with poetry and political rhetoric and sobriety. Something to do with a devotional by theologian Fleming Rutledge and thoughts on atonement.

Hendrickson recalls, for example, the prodemocracy protests in Beijing’s Tiananmen Square in 1989. As the authoritarian government responded with force, a journalist photographed an unidentified man standing in the way of a column of tanks.

“He’s holding a takeout bag,” he said. “He’s not Rambo. He’s not some grand militant hero. He’d just had enough of it.”

Then there were the poems.

“There are some particularly powerful pieces of poetry that have gotten past my crusty exterior and had purchase on me,” he said.

One was by Ukrainian-American poet Ilya Kaminsky, called “We Lived Happily During the War.” It is just 12 lines long, but it ends, “we (forgive us) / lived happily during the war.”

Joel Carillet

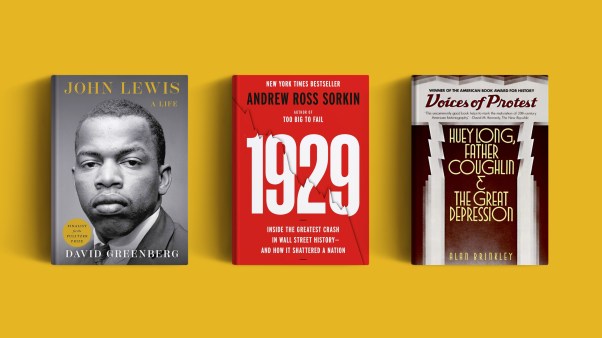

Joel CarilletHendrickson said a full account of why he is in Ukraine would also have to include the principled politics of people like the late senator John McCain and the journalist and historian Anne Applebaum. Their words shaped his thinking over the years.

Finally, there was, as he put it, “the whole God, Jesus, Bible thing.”

For the past several years, Hendrickson has been in the habit of reading passages from a book over the phone with his mom and his son. On the fourth day of Russia’s full-scale invasion, February 27, their reading was from Means of Grace, a devotional of writings from Fleming Rutledge’s sermons. It was about the transfigured Christ turning his face toward Jerusalem, where suffering and death waited. Rutledge writes that love must come down, because “love must go where it is most needed in the valley of the shadow of death.”

“Mountaintop experiences of spiritual nourishment and encounter can be wonderful, but you’re not supposed to stay on the mountain,” Hendrickson said. “You then still have to actually go into Jerusalem, even if there are some things waiting for you that you don’t want to run into.”

A week or two after the war began, as the poetry, rhetoric, theology, and news swirled around him, he felt a weight settle on him. The idea came that maybe he should go. But he didn’t want to go for the wrong reasons.

And it’s not like he didn’t have plans. He had just sunk money into a bus, which he intended to convert into a livable space, then enroll in a nursing program. Then he looked at his passport and noticed it had just expired.

“Are the obstacles along the way challenges to overcome?” Hendrickson said. “Or is this like, ‘Dude, you don’t even have a passport’?”

He thought, as he has for years, about the sheep and the goats passage in Matthew 25 and how one plays that out: “I was hungry and you didn’t feed me. I was being shelled and you didn’t evacuate me.”

Hendrickson, who has been sober for 11 years, was also thinking about atonement.

“It’s not a kind of guilt or transactional thing,” he said. “It’s more that ‘You, Brad, have been plucked from the sea of chaos and have gotten the chance to dry off a bit’—no pun intended—‘and are on the deck of the ship. You’ve been saved, but now you’re part of the rescue crew. Suit up. You’re part of this ongoing mission.’”

Hendrickson did some of his processing out loud with Joshua Hill, the rector at St. Alban’s, an Episcopal church in Cape Elizabeth, Maine. The priest told CT he was not used to Episcopalians saying God wanted them to uproot their lives and go abroad. But he listened and became convinced this was from God.

Joel Carillet

Joel Carillet“He’s listening to God,” Hill said. “He’s trying to be faithful to what God is doing in the world, plain and simple. There’s nothing complicated about it—and it’s very complicated.”

Hendrickson’s mother had a similar response. Sheryl Campbell, a Presbyterian Church (USA) minister, had just preached on Psalm 27 about trusting God while under siege and surrounded. Christians, she said, need to remember that God will not spare them from all trouble but will faithfully see them through and use them in the process.

“When we walk through that which is deathly, because of the power and victory of God in Jesus Christ, it is the shadow of death and not death itself,” she preached. “God is using us in someone else’s life so that the glory and power and love of God may be made known.”

Campbell’s church in Sun City, Arizona, raised funds for Hendrickson. The people at St. Alban’s also contributed, and Hill offered logistical help.

Hendrickson flew to Germany in late March 2022. He caught another flight to Romania and then was driven across the border into western Ukraine. From there he joined an aid convoy east.

Joel Carillet

Joel CarilletBy early summer, he had found his footing and saw what kind of help he could best provide.

He got a vehicle and started doing what he had done for UPS—making deliveries. He started driving aid in and people out of frontline areas. When asked how many people he’s evacuated, he says dozens and dozens, maybe hundreds—he doesn’t keep a tally.

Artur Spitsyn, deputy head of the emergency services in Bakhmut, told CT that Hendrickson’s presence matters in more than just material terms. His presence “raises the spirits of people in terrible conditions,” Spitsyn said. He added that even the cats and dogs get some love and care when they cross Hendrickson’s path.

As his period of service has stretched into almost a full year, Hendrickson has found the challenges of discernment continue. The flat tire incident was just one of many close calls.

“When do I say, ‘The war will continue on but the war is over for me’?” he said. “This is absolutely not some romanticized, martyr-hero … thing. … I’ve got a bus to get back to.”

He has other ideas, too. He thinks that when he returns to Maine, he might like to be a chaplain.

For at least a while longer, though, he remains on the frontlines of war. And he continues to think about the depth and complexity of his answer to the simple question of why he’s there.

Joel Carillet is a photojournalist based in East Tennessee. He reported this story from Ukraine.