There’s a story my family has told since before I was born about my great-uncle Johnny. When his four daughters were teenagers, the family took a long trip in which they had to stop in a familiar town for dinner.

About 30 minutes out, Aunt Betty Jane and the girls started talking through the variety of eating options and, after 10–15 minutes of deliberation, they agreed upon the best restaurant. But when they arrived in town, Uncle Johnny, who hadn’t said a word, pulled into a different restaurant, got out of the car, and walked silently inside, leaving five dumbfounded women looking at each other and wondering what had just happened.

That story—at least, a sinister reading of it—came to mind as I tried to process last week’s revelation of an amicus brief filed in April by legal counsel for the Southern Baptist Convention, the SBC’s Executive Committee, Lifeway Christian Resources, and The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary.

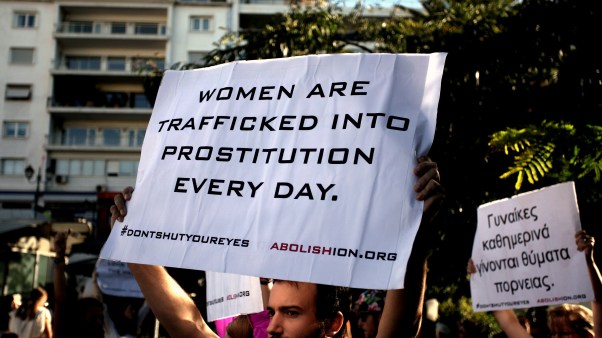

The case is Samantha Killary’s lawsuit against the city government of Louisville, Kentucky, where law enforcement employees allegedly enabled her years-long sexual abuse by her father, also a police officer.

No SBC entity is named in the lawsuit. But because it is similar to other lawsuits being brought against the SBC and the Executive Committee in Kentucky, legal counsel apparently advised these entities to file the amicus brief, encouraging the state Supreme Court to exclude “non-offender third parties” from Kentucky’s recent change in the statute of limitations for abuse claims.

This may protect the SBC from legal liability, but it harms Killary and excuses the institution that hurt her. It is an enormous betrayal to abuse survivors and our allies for accountability within the SBC, and the consequences will—and should—be grave.

In the SBC version of my family’s story, the passengers riding in the car are the abuse survivors and advocates who—following in the footsteps of Christa Brown, Debbie Vasquez, Dee Ann Miller, and others who have demanded change for decades—have been working within the convention since the Houston Chronicle’s “Abuse of Faith” investigation shocked many Southern Baptists in 2019. That year, Southern Baptists launched a number of anti-abuse programs.

The Caring Well initiative and Church Cares curriculum were quickly created and made available to equip churches to prevent and address abuse. A resolution passed during the annual meeting that included a specific call “to ensure that … statutes of limitations (criminal and civil) do not unduly protect perpetrators of sexual abuse and individuals who enabled them.” The Ethics and Religious Liberty Commission changed its fall conference theme to “Caring Well: Equipping the Church to Confront the Abuse Crisis.”

Then, during the 2021 meeting in Nashville, messengers overwhelmingly approved a motion calling for a third-party investigation into the mishandling of abuse claims by the Executive Committee. Months later, after contentious pushback, the Executive Committee voted to waive attorney-client privilege so that the investigation by Guidepost Solutions could be thorough.

As a Southern Baptist pastor who has shepherded abuse survivors for 18 years and as a survivor of grooming and abuse by SBC conservative resurgence luminary Paul Pressler, I counted these steps as major victories.

The genius of Southern Baptist polity—in which any church messenger can make a motion or submit a resolution or propose directives to entity trustees—was finally working in the favor of survivors. While some found the progress to be too little, too late, real energy was stirring. In the back of the car, it seemed like we were finally heading in the right direction.

And then the car pulled into the parking lot of Killary’s case, and the SBC’s considerable legal resources were put to work against a survivor’s pursuit of justice and to protect the institution that enabled her abuse.

Not only was this move not discussed by anyone in the car, it was diametrically opposed to every step our gathered convention had affirmed over four years. Here we are—survivors and pastors and therapists and attorneys who thought things were changing for the better—wondering what had just happened.

And lest my driver metaphor sound reductive, let me be clear: This is not a story about an avuncular man being stubborn. This is a story about pure betrayal.

The most insidious element is that we don’t even know who the driver is. Is legal counsel driving the SBC? Is it one of the trustees? Or the presidents of these four entities?

After the brief became public, multiple Executive Committee members said they never knew about it. “Not one SBC Executive Committee trustee was involved in the decision to join this amicus brief,” the committee said in a statement.

That statement reports that the brief was approved on “the advice of legal counsel, and only in response to their request,” but it studiously omits the brief’s origin story. Even the lawyers are let off the hook: “Counsel for the SBC Executive Committee reviewed the brief and recommended it be joined.” If counsel only reviewed it, who wrote it?

SBC president Bart Barber has admitted to approving the brief on a short deadline during a busy afternoon of meetings. (“Does it even lie within the power of the SBC President to make decisions about amici curiae unilaterally on behalf of the Convention?” he asks as part of his apology. “I think probably not.”)

But Barber’s statement likewise doesn’t explain where, why, and with whom the brief originated. He simply describes receiving “an email from the SBC’s legal team making me aware of this brief and recommending that we join it.”

Who is responsible for this? Who is to blame? Who is driving the SBC, if not our elected and appointed leaders? Who has dismantled, in one legal move, any semblance of institutional trust so many have worked to rebuild? Whoever they are, they apparently feel no need to explain themselves.

I do not claim to speak for every SBC survivor and advocate. But those with whom I have been in contact for the last week feel this betrayal in a visceral way that words strain to capture. Still, let me give it a shot.

Years ago, I heard the (apocryphal, I’m guessing) story about a teen on a mission trip who, when the power went out during a worship service, started to pet the cat that sidled up next to her on the windowsill. Only, when the lights came on, she realized it wasn’t a cat. It was a large, furry tarantula.

Magnify that jump-scare 1,000 times to know the horror of the woman who, years later, realizes her youth pastor didn’t love her when he wanted that special alone time with her. He was raping her.

Inhabit the terrified confusion of the 13-year-old who bravely tells her pastor how a revered deacon touched her, only to be told to forgive him immediately and tell no one else.

Or you can enter the emotional vertigo swirling around me when I pieced together that Pressler didn’t actually want to invest in me as a next generation leader in the battle for the Bible. He just wanted to see me naked—or worse.

What every survivor has had to come to terms with is betrayal. It’s betrayal not only by the abuser but by the leaders and community that kept the abuse quiet or refused to ask questions for the sake of the greater “good.”

That betrayal became very real and very present again last week. First, there was the news of the amicus brief itself. Then, we read our Executive Committee officers’ statement justifying inserting the SBC into a lawsuit—one, lest we forget, in which it is not named and had no legal risk—as a means of protecting “legal and fiduciary interests” and “defend[ing] itself.”

It’s not a cat. It’s a tarantula.

Or, if you’ll permit me both metaphors: We didn’t know that the man driving the car wasn’t listening to us and our allies. We didn’t realize that our plans wouldn’t matter. We didn’t realize we were again cozying up to something lethal.

I’ve heard two responses from survivors and advocates that I hope will speak to those wrestling with their place in the SBC or any troubled organization.

The first is simply: “I’m out.” You don’t have to stay in the car and wait for the driver to ignore you again. It’s okay to leave.

One woman who has experienced incredible institutional harm has intentionally used the word “escaped” rather than “left.” In an organization where trust has been betrayed, this language is far from excessive. Each person must ask God for wisdom to know when their participation tilts from being a voice for change from the inside to being complicit in enabling a corrupt institution. And we must respect each other’s obedience to God to stay or go.

Second, another survivor shared how this betrayal has served as an invitation for her to draw near to Jesus and leave these heavy burdens at his feet. This is no cliché but comes from the painful depths of one who has been sexually and spiritually abused. Like Paul’s desire to “share [Christ’s] sufferings” (Phil. 3:10, ESV), we can taste a solidarity with the Savior who was also betrayed by those who knew the Scriptures best.

Such spiritual nearness to Jesus—enhanced by connection with those who have proven themselves safe and trustworthy—can sustain us during times of institutional upheaval and transition. It can preserve us, too, from perpetuating the unhealthy patterns to which we were exposed.

I do not know what all of the past week’s news will mean for the Southern Baptist church I pastor. Whether to stay in the convention is a decision that must be made by our church leaders and congregation.

But what I know for sure is that unless this shadowy driver—or, most likely, drivers—reveals his identity, repents of these actions, and displays evidence of pursuing repair over self-preservation, I’m not getting back into the car.

Chris Davis is senior pastor of Groveton Baptist Church in Alexandria, Virginia, and the author of Bright Hope for Tomorrow: How Anticipating Jesus’ Return Gives Strength for Today.