"What did you give up for Lent?" I had grown up in Baptist and other conservative evangelical churches, so my friend's question held no meaning. I figured it was like a second chance at a New Year's Resolution for those who had already abandoned theirs.

Even around here at the Christianity Today offices, where Christian History is based, it seems that Ash Wednesday passed with little notice. There were just as many donut trays by the coffee pots, and just as many hamburgers in the lunch room.

That's surprising, especially since Lent is one of the oldest observations on the Christian calendar. Like all Christian holy days and holidays, it has changed over the years, but its purpose has always been the same: self-examination and penitence, demonstrated by self-denial, in preparation for Easter. Early church father Irenaus of Lyons (c.130-c.200) wrote of such a season in the earliest days of the church, but back then it lasted only two or three days, not the 40 observed today.

In 325, the Council of Nicea discussed a 40-day Lenten season of fasting, but it's unclear whether its original intent was just for new Christians preparing for Baptism, but it soon encompassed the whole Church.

How exactly the churches counted those 40 days varied depending on location. In the East, one only fasted on weekdays. The western church's Lent was one week shorter, but included Saturdays. But in both places, the observance was both strict and serious. Only one meal was taken a day, near the evening. There was to be no meat, fish, or animal products eaten.

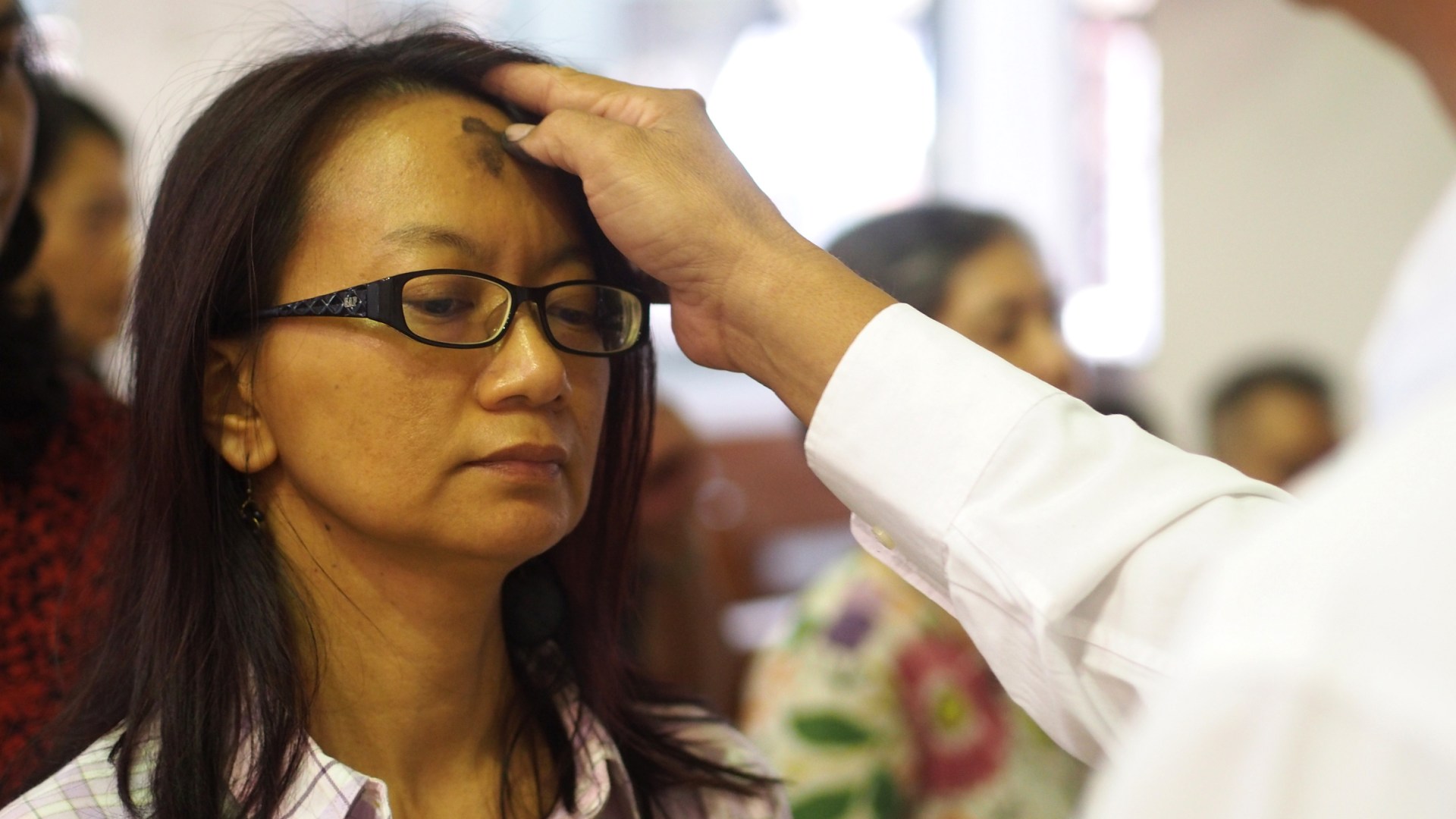

Until the 600s, Lent began on Quadragesima (Fortieth) Sunday, but Gregory the Great (c.540-604) moved it to a Wednesday, now called Ash Wednesday, to secure the exact number of 40 days in Lent—not counting Sundays, which were feast days. Gregory, who is regarded as the father of the medieval papacy, is also credited with the ceremony that gives the day its name. As Christians came to the church for forgiveness, Gregory marked their foreheads with ashes reminding them of the biblical symbol of repentance (sackcloth and ashes) and mortality: "You are dust, and to dust you will return" (Gen 3:19).

By the 800s, some Lenten practices were already becoming more relaxed. First, Christians were allowed to eat after 3 p.m. By the 1400s, it was noon. Eventually, various foods (like fish) were allowed, and in 1966 the Roman Catholic church only restricted fast days to Ash Wednesday and Good Friday. It should be noted, however, that practices in Eastern Orthodox churches are still quite strict.

Though Lent is still devoutly observed in some mainline Protestant denominations (most notably for Anglicans and Episcopalians), others hardly mention it at all. However, there seems to be potential for evangelicals to embrace the season again. Many evangelical leaders, including Bill Bright of Campus Crusade and Jerry Falwell are promoting fasting as a way to prepare for revival. For many evangelicals who see the early church as a model for how the church should be today, a revival of Lent may be the next logical step.