It is difficult to fathom today why the desert fathers did what they did, or why the church, East and West, was so taken by their example for the next millennium. It requires a great deal research and historical imagination to see what the desert monks were getting out of their ascetic discipline.

Belden Lane, a Presbyterian professor of theology at St. Louis University, is one who has done the research and has the historical imagination. His The Solace of Fierce Landscapes: Exploring Mountain and Desert Spirituality (Oxford, 1998) is a brilliant analysis of how geography has played a vital role in the history of Western spirituality. Christian History asked Professor Lane to help us grasp the attraction of desert asceticism throughout Christian History.

Why did the desert fathers choose to work out their spirituality in the desert?

They sought God, first of all, and they knew that God was most easily found in a place without distractions. Second, the desert was also a marvelous laboratory for dealing with the self, which was their other major spiritual project.

How do you handle the ego and its anxiousness, its constant need for support? You walk into the desert, which doesn't care one bit about who you are or what you bring to it. That kind of terrain offers a marvelous antidote to the problem of the ego, the false self.

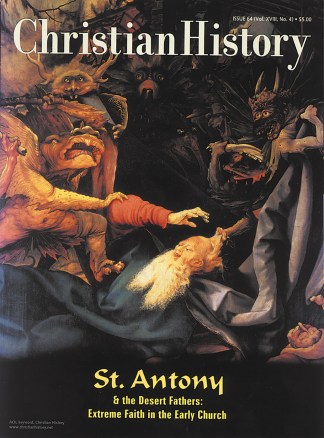

In the Bible and Greco-Roman culture, the desert is not so much a place of spiritual growth but a place of evil and temptation. Didn't the monks believe that?

They did, and that is another reason they went into the wilderness. They found precedents in the life of John the Baptist (you won't find a desert monastery without an icon of John the Baptist) and especially in Jesus. Throughout his life, Jesus withdrew into the desert to pray. He began his ministry in the wilderness, being tempted for 40 days. Likewise, Antony started his ministry by going into the desert to empty himself and face temptation there.

The desert is a place where you expect the temptations of hunger, of power, of beauty—the things the desert lacks are the things you find yourself wanting desperately. The monks looked on demons and temptation as aides to their spiritual lives. But they were not overwhelmed by trials and temptations. Instead, they found God in the midst of temptation and struggle.

Today, many go into the wilderness to "get back to nature." Was that part of the monks' motivation?

No. It's so easy for us to romanticize their motivation today. Abba Macarius in Egypt was said to be a lover of the desert, but this was only after spending years there. For the monks, the desert was primarily a training ground.

How did the desert as such shape these monks' spiritual lives?

The desert asks two questions: What do you learn to ignore? And what do you learn to love? In other words, how do you let go, and what do you hold onto? Those are the basic dimensions of the spiritual journey that the desert monks went through as they embraced the desert.

Let me paraphrase one of the best illustrations of this, found in Sayings of the Desert Fathers: A young man, a spiritual groupie of sorts, comes to Scetis, west of the Nile, to seek out the great monk Abba Macarius. He asks Abba Macarius, "How do I get to be a holy man? I want to be a holy man. And I want to be one tomorrow."

Macarius smiles and says, "Spend the day tomorrow over at the cemetery. I want you to abuse the dead for all you're worth. Throw sticks and stones at them, curse at them, call them names—anything you can think of. Spend the whole day doing nothing but that."

The young man must have thought the great monk was crazy, but he spent the next day doing everything he was told. When he returned, Abba Macarius asked him, "What did the dead people say out there today?"

The young man responded that they didn't say a thing. They were dead. Macarius said, "Isn't that interesting? I want you to go back tomorrow, and this time spend the day saying everything nice about these people. Call them righteous men and women, compliment them, say everything wonderful you can imagine."

"The desert is a perfect

place to let go of the

need for recognition"

—Belden Lane

So the young man went back the next day, did as he was told, and returned to Macarius. The monk asked him what the dead people said this time.

"Well, they didn't answer a word again," replied the brother.

"Ah, they must indeed be holy people," said Macarius. "You insulted them, and they did not reply. You praised them, and they did not speak. Go and do likewise, my friend, taking no account of either the scorn of men and women or their praises. And you too will be a holy man."

It's a wonderful story that asks two questions: What do you ignore? The answer is the scorn and praise of others. The other question is more indirect—What do you love? That is, since you are not going to be motivated by what others think, what are you going to give yourself to fully?

But how is it possible to learn love when you're solitary?

The monks learned that the desert teaches you how to live apart from others, how to live without compulsively needing them to give you worth or make you feel loved. In the desert, you learn how to live with yourself. Only then are you capable of giving love—sacrificial love that accepts or needs nothing in return.

Let me give an example from our lives, because even when we live in the city, we can have this type of desert experience. There's a point when you realize you have to let go of what you love most if you ever hope to really keep it. And only when you reach that point (e.g., in your career or your marriage or your deepest relationships with others), when you move beyond a compulsive need for them. Only then is it going to be possible really to love for the first time.

It's incredibly painful letting go. But once you do that, there is an incredible sense of the desert, as Isaiah says, blossoming like a rose. Suddenly in the place of abandonment, in the place where you let go of everything you knew, you realize that what you could not hold God gives back. And love is born there in the very place where you had lost everything.

Now as the monks learned, the desert makes no promises. If you're going out there to suddenly become a deeply loving person, if like the young man you want to become holy, there are no guarantees. It is only at profound risk—letting go, ignoring yourself and the distractions of the world—that love and compassion might occur. But as many mystics, East and West, have discovered, "The experience of emptiness engenders compassion."

In a lot of the desert father stories, it feels as if the monks practiced ascetic disciplines to earn salvation.

You could interpret it that way on a surface level. But I see them living out what medieval mystic Meister Eckhart once said, that the spiritual life isn't so much a matter of addition as subtraction.

Though we Protestants talk about justification by faith (versus by works), we often act as if the key to the spiritual life is adding all the active virtues, doing great things for God, sharing the gospel with others, and the like. Eckhart said, no, it's a matter of subtraction. How much can you let go of? It's not a matter of anxiously having to prove yourself to your teachers, to your parents, or to God so as to finally make yourself acceptable. It's a matter of letting go of all those compulsive needs for approval and recognizing that only after you abandon those compulsions will you be able to accept God's utterly free grace that comes in the gospel, in Jesus.

The desert is a perfect place to let go of the need for recognition. I love the image of the canyon cliff that Gregory of Nyssa used back in the fourth century. Being on top of that cliff, in a place of beauty and uneasiness—that's where you discover the majesty, greatness, and glory of God. You look at that canyon cliff, think about it being there thousands, maybe millions of years, and you ask yourself, how did that canyon cliff change on the day your personal world fell apart?

What's an example of that?

For me, that was the day my father was tragically killed when I was 13, and I thought the whole world had fallen apart. What did that canyon cliff do that day? Or how did it change on the day of your divorce, or the day you admitted your dependence on alcohol, or the day you finally shared a hidden shame with someone else?

And you find, sitting there watching that canyon wall, that it didn't change at all. In the midst of your world falling apart, something didn't change. It was waiting, staying there as if for you, in the same way that God does not change. That stone cliff, a metaphor of God, invites you to pour out all the grief and anguish you can muster, then accepts it all without rebuke, receives it all right there in the desert.

Something amazing happens at that point. When you become silent enough and empty enough, pouring out your needs to God in that desert place, you are able for the first time to hear what you had never heard before, and that's a single word whispered by Jesus: love. It's one of those words that you can't hear until you are utterly silent and utterly empty.

Speaking about what the most devout desert monks had experienced, John Climacus wrote, "Lucky the man who longs for God as a smitten lover does for his beloved."

To me, this is what attracted and held monks in the desert, and why it still attracts some souls to this day.

For more on Belden Lane, see his bio at:

Faculty of American Studies Department at SLU http://www.slu.edu/colleges/AS/amers/faculty.html

Copyright © 1999 by the author or Christianity Today/Christian History magazine. Click here for reprint information on Christian History.