In this series

Crossing the dry Egyptian desert, a band of philosophers finally arrived at the “inner mountain,” the monastic abode of a Christian named Antony. The skeptical scholars asked the illiterate old man to explain the inconsistencies of Christianity, and after they got started, they ridiculed some of its teachings—especially that God’s Son would die on a cross.

Antony, who spoke only Coptic (not Greek, the international language of the day), answered through an interpreter. He began by asking, “Which is better—to confess a cross, or to attribute acts of adultery and pederasty to those whom you call gods?” After questioning further the reasonableness of paganism, he moved to the central issue.

“And you, by your syllogisms and sophisms,” he continued, “do not convert people from Christianity to Hellenism, but we, by teaching faith in Christ, strip you of superstition. … By your beautiful language, you do not impede the teaching of Christ, but we, calling on the name of Christ crucified, chase away the demons you fear as gods.”

A crowd of seekers stood by, waiting to see Antony, and among them were some men who were “suffering from demons.” Antony asked that the men be brought forward. He called on Christ, made the sign of the cross over them three times, and, according to one ancient account, “immediately the men stood and were sound, coming to their senses and giving thanks to God.”

The Greek philosophers were astonished, but Antony quickly said, “Why do you marvel at this? Is it not we who do it, but Christ, who does these things through those who believe in him.”

The philosophers then departed, embracing Antony as they left, saying they “had benefited from him.”

This story, and others like it, show that by the end of his life, the solitary Antony had gained a reputation across the Mediterranean world. Not only simple people but the sophisticated and mighty sought him out. His life and words inspired fellow Christians to greater devotion and, sometimes, moved pagans to convert. But it wasn’t his wisdom and eloquence that astounded people as much as his laser-like devotion to Christ.

This devotion expressed itself in a way that was as impressive to his age (as well as to Christian Europe for another 1,000 years) as it is strange and off-putting to us today. The way is called asceticism, or originally, “the discipline,” and the institution it created is called monasticism.

Although Antony is sometimes considered the founder of monasticism, he was not. But he put monasticism on the Christian map because of his extraordinary practice of monastic disciplines. In the novel and movie The Natural, baseball player Roy Hobbs longs to be “the best there ever was.” It terms of how early and medieval Christians understood the spiritual life, Antony was indeed considered the best there ever was.

Antony was born in A.D. 251, an “Egyptian by race” (all quotations are from Athansius’s The Life of Antony, from which the above account comes as well). Egypt was under Roman control and Christians were still subject to periodic bouts of persecution. But Egypt was also home to one of the most vibrant Christian communities in the empire and had already produced two of the church’s greatest minds—Clement and Origen. Consequently, many Egyptians of wealth and influence were finding their way into the church.

Such was the case with Antony’s parents, who were “well born and prosperous,” and who raised Antony in the faith; Antony regularly attended church with his parents.

Though he was not interested in learning how to read or speak anything but his native Coptic, early on he showed a keen interest in hearing Scripture read.

When Antony was between 18 and 20, two events took place that altered his life trajectory. First, both his parents died—how exactly, we don’t know, though plague is a likely candidate. Antony now found himself caring for “one quite young sister,” as well as the family estate of over 200 acres.

The second event took place about six months later. One Sunday, as Antony made his way to church, he was contemplating the biblical passage that described early Christians’ selling their possessions and giving everything to the poor (Acts 4:32-37). When he stepped into the church, the Gospel was being read, and Antony heard, “If you would be perfect, go and sell all that you have and give to the poor; and come follow me and you shall have treasure in heaven.”

Antony was startled—it was “as if the passage were read on his account.” He did not quibble nor hesitate, but obeyed as if it had indeed been spoken to him personally. He donated his family estate to his town (though historians are unclear as to which town that was), sold or gave away the rest of his possessions, put his sister into the care of a convent, and “devoted himself from then on to the discipline rather than the household.”

“The discipline” included a variety of practices, from constant prayer and working with one’s hands to severe fasts and sleep deprivation. He took up with a Christian hermit living in a neighboring village, and over the next several years visited many others: “He observed the graciousness of one, the eagerness for prayers in another; he took careful note of one’s freedom from anger and the human concern of another. … He admired one for patience, and another for fastings and sleeping on the ground. … He marked likewise, the piety toward Christ and the mutual love of them all.”

Mutual love, perhaps, but there was also in early monasticism a competitive spirit, in which monks sought to outdo one another in “the discipline.” This is where Antony shined; he aimed to “be second to none of them in moral improvements”:

“His watchfulness was such that he often passed the entire night without sleep, and doing this not once, but often, he inspired wonder. He ate once daily after sunset, but there were times when he received food every second and frequently even every fourth day. His food was bread and salt, and drinking he took only water. … A rush mat was sufficient to him for sleeping, but more regularly he lay on the bare ground.”

Antony believed, as did most Christians of his era, that “the soul’s intensity is strong when the pleasures of the body are weakened” A well-rested body, satiated with pleasure, and basking in the good things of life, becomes spiritually lazy. That is, no pain, no gain. Christians like Antony took literally the sayings of Jesus about the incompatibility of mammon and God, about earthly treasures being a stumbling block to heavenly joy, and so on. Not many took up the discipline as radically as did Antony, but even those who didn’t recognized the need to discipline the body and its desires, sticking to some physical and spiritual regimen.

Though Antony already impressed many of the townspeople, he remained unsatisfied with his progress. So he moved “some distance from the village,” entered a tomb, and had a friend, who agreed to supply him with bread, close the entrance.

It was here that Antony experienced some of his most horrific demonic attacks.

Staving off demons

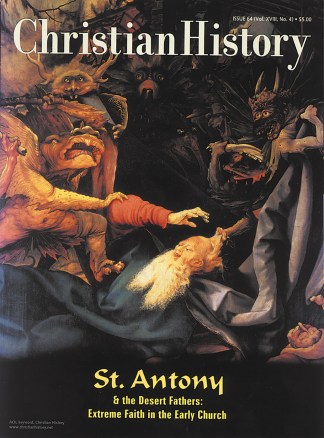

Antony’s hair-raising battles with demons are the most tantalizing parts of Athanasius’s biography and became a popular subject for medieval artists. Today it is hard to determine exactly what it is that Antony experienced: were these dreams (nightmares), encounters with actual spirits, psychological wrestling, hallucinations, or what? Whatever they were, Antony’s biographer clearly used them to illustrate Antony’s spiritual strength, or better, how Christ aided Antony.

Early encounters seem to be of the usual sort—”a great dust cloud of considerations” one would expect Antony to experience: “The devil … attempted to lead him away from the discipline, suggesting memories of his possessions, the guardianship of his sister, the bonds of kinship, love of money and of glory, the manifold pleasure of food, the relaxations of life, and finally the rigor of virtue.”

But things turned violent after Antony was closed up in the tomb: “A multitude of demons … whipped him with such force that he lay on earth, speechless from the tortures.” When his friends found him, they took him for dead at first. After he was taken back to the village, he recovered and returned to the tombs, where he underwent some of his most vivid spiritual experiences:

“The place was immediately filled with the appearances of lions, bears, leopards, bulls, and serpents, asps, scorpions and wolves, and each of these moved in accordance with its form. The lion roared, wanting to spring at him; the bull seemed intent on goring; the creeping snake did not quite reach him; the onrushing wolf made straight for him—and altogether the sounds of all the creatures that appeared were terrible, and their ragings were fierce.”

Antony felt as if he had been struck or wounded. But Antony only mocked the demons: “If there were some power among you, it would have been enough for only one of you to come. … It is a mark of your weakness that you mimic the shapes of irrational beasts.”

After being assaulted like this for who knows how long, Antony looked up and saw “the roof being opened, as it seemed, and a certain beam of light descending toward him. Suddenly the demons vanished from view.”

A confused Antony entreated, “Where were you? Why didn’t you appear in the beginning, so that you could stop my distresses?”

A voice answered, “I was here, Antony, but I waited to watch your struggle. And now, since you persevered and were not defeated, I will be your helper forever, and I will make you famous everywhere.”

Now Antony “was even more enthusiastic in his devotion to God.” He went deeper into the desert and ran across a long-deserted fortress with a spring or well within. The now 35-year-old Antony entered the fortress, shut and barred the gate (again, after making arrangements with friends for food drops), and began living there alone.

With this, his reputation grew greater still, so that over the years, more and more people journeyed to his fortress in the hopes of catching a glimpse of this desert hero. Some reported overhearing Antony battle demons “emitting pitiful sounds and crying out.” Others received counsel through the gate. And many, inspired by his example, took up the discipline themselves.

One day, 20 years into this way of life, Antony, “having been led into divine mysteries and inspired by God,” opened the gate and emerged. The crowd gathered there was “amazed to see that his body had maintained its former condition, neither fat from lack of exercise, nor emaciated from fasting and combat with demons.” Even more to the point, they were impressed that “the state of his soul was one of purity, for it was not constricted by grief, nor relaxed by pleasure. … Moreover, when he saw the crowd, he was not annoyed any more than he was elated at being embraced by so many people.”

(In this and other descriptions, Athanasius, as a theologian battling Arianism, was also trying to show Antony as an example of God’s ultimate purpose in Christ: God became man that we might become godlike.)

With this, Antony began his public ministry, and Athanasius reports that he healed the sick, exorcized demons, reconciled enemies, and consoled the mourning. He also “gave grace in speech,” speaking long with those who sought spiritual direction. His specialty seems to have been dealing with demons and urging others on in the discipline, saying, “Let us not consider, when we look at the world, that we have given up things of some greatness, for even the entire earth is itself quite small in relation to all of heaven.”

As a result, “by the attraction of his speech, a great many monasteries came into being, and like a father he guided them all.”

Going to a new level

For the rest of his life, Antony moved back and forth between monastic seclusion and public ministry, not only in the desert, but also in the city. When Emperor Maximian began persecuting Christians in 311, Antony went to Alexandria to encourage those on trial, comfort the imprisoned, visit the convicted (one of Maximian’s punishments was to blind one eye, hamstring one leg, and then send the guilty into the mines) and stand by others during execution. While others rushed into hiding when the government put on more pressure, Antony continued to appear in public. But authorities refused to touch him, fearing perhaps that the martyrdom of ascetic this hero would not sit well with the public, pagan or Christian.

When Maximian’s persecution ended after a couple of years, Antony returned to his desert cell and “was there being martyred daily by his conscience, doing battle in the contests of faith.” And again he raised the level of his discipline: he began wearing a hair shirt (with the bristles rubbing constantly against the skin) and he stopped bathing (considered a luxury).

Though he wanted nothing more than to remain alone in prayer, people kept pestering him. Increasingly annoyed with the interruptions, he sought escape by traveling up the Nile. But as he waited one day to hop on a passing boat, he heard a voice “from above” saying, “If you truly desire to be alone, go now into the inner mountain.”

He was confused as to exactly what that meant, but he joined some traveling Saracens who were going east. About 100 miles southeast of Cairo, he saw a hill that he sensed was the place revealed to him, and there he settled down.

Rather than continue to depend on donations, Antony planted wheat and some vegetables to sustain himself—and to offer something to the inevitable visitors (who kept arriving). A handful of monks joined him (including Athanasius for a time) and witnessed his asceticism, overheard his battles with demons, and sought his spiritual counsel.

Antony was about 40 by this time, and for the next 65 years (he lived to age 105), this was home base. Antony’s remarkable devotion and longevity enhanced his reputation for sanctity. Athanasius records a number of remarkable stories from this period, and the historian is hard pressed to decipher what is factual and what belongs to the realm of parable.

In many stories, Antony is clearly a “new Adam,” an example of restored humanity, one who is not subject to creation but master of it. In one incident, Antony scolds animals who had trampled his garden, and from then on, they no longer do so. In another story, a pack of hyenas threaten to attack him, but when Antony tells them to depart, they obey.

Other stories show Antony enjoying a variety of mystical experiences. More than one story tells of his clairvoyance; for example, one day in prayer he saw two monks journeying to see him lying beside the road miles away, dying of thirst. (By the time monks sent by Antony arrived to help the travelers, one of them had already died).

He also displayed the gift of prophecy: he told individuals why they had come to see him before they told him themselves. He even was reported to have an out-of-body experience: “He felt himself being carried off in thought, and the wonder was that while standing there, he saw himself, as if he were outside himself.”

Though Athanasius includes such stories to impress readers with Antony’s holiness, time and again he also reminds readers, “Working with Antony was the Lord, who bore flesh for us, and gave to the body the victory over the devil, so that each of those who truly struggle can say, ‘It is not I, but the grace of God which is in me.” And he shows Antony himself pointing people elsewhere: “He asked that no one marvel at him on his account, but rather that they marvel at the Lord.”

By the time he was 105 years old, Antony’s body was frail, his teeth were completely gone, and he knew death was near. He told his companions how to dispose of his few possessions (one sheepskin cloak, for example, was to go to Athanasius). Then he exhorted them, “Be watchful and do not destroy your lengthy discipline … Strive to preserve your enthusiasm . …You know the treacherous demons … do not fear them, but rather draw inspiration from Christ always, trust in him.”

After he died, he was buried in an unmarked grave, the location of which is lost to history.

“He is famous everywhere,” Athanasius noted at the end of his biography, “and is marveled at by everyone, and is dearly missed by people who never saw him.”

For a thousand years hence, Antony was considered the spiritual best that ever was, the prototypical monk and the new Adam, an example of what God could do through one devout soul.

As such, Antony inspired the monastic movement, which more than any other Christian institution, is responsible for evangelizing and then Christianizing Europe—an ironic legacy for an illiterate Egyptian who strove to live far from civilization.

Mark Galli is the editor of Christian History.

For more information on this topic, see:

Medieval Sourcebook: Athanasius: Life of Antony, Full Texthttp://www.fordham.edu/halsall/basis/vita-antony.html

Catholic Encyclopedia: Anthony, Sainthttp://www.knight.org/advent/cathen/01553d.htm

Copyright © 1999 by the author or Christianity Today/Christian History magazine. Click here for reprint information on Christian History.