Confessiones

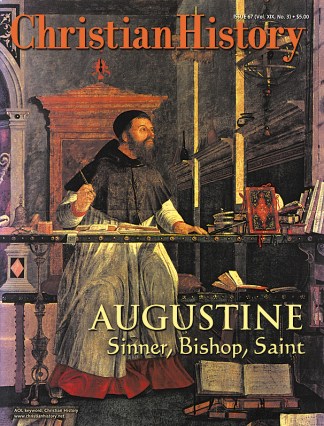

Aurelius AugustinusA.D. 400This book is something of a first, and its title might mislead later readers. What Augustine has written, a few years after becoming pastor-in-chief of the church at Hippo (in Roman North Africa), is an extended doxology: thankful praise addressed to God.

He begins with quotations from two psalms: “You are great, Lord, and highly to be praised: great is your power, and your wisdom beyond measure.” The phraseology and devotional ethos of the Psalter pervade the whole work.

Narrative, however, is central; as Augustine commented later, “The first ten books are written about myself.” The last three are searching meditations on themes suggested by early Genesis.

Spiritual and intellectual autobiography on this scale is unprecedented. Augustine openly describes “the good things and the bad things in my life.” He confesses much sin and error—but only to magnify the ever-resourceful grace of God.

Augustine is a profound analyst of the restless twistings of the human soul “turned in on itself” in flight from God. Deeper still is his insight into God’s tireless pursuit of his wandering spirit.

Confessiones can be read on a number of levels, which should guarantee perennial appeal. It lays out, for example, a canvas of many of the religions and philosophies competing for allegiance on the cusp of the fifth century. Augustine was pulled now this way, now that; he spent much of his twenties with the Manichees (a missionary-minded Gnostic movement of Persian origin), then read the Neo-Platonists before finally joining the Catholic camp.

On another level, Confessiones sketches an entrancing mother-son relationship. With simple godliness, Monica tenaciously prayed and wept her wayward genius of a son into commitment to Christ and his Church. Once he was safely in the fold, Monica was free to die—after an experience of spiritual ecstasy with Augustine “in the presence of Truth.”

Ambrose, the eloquent preacher and heavyweight Christian thinker, also figures prominently. As bishop of Milan, he clinched Augustine’s return to the faith he first learned on his mother’s knee.

Though the author often conveys vivid immediacy, this is no diary. Augustine is writing from memory, a dozen years or more after the critical years of his conversion and baptism. The narrative thread follows no neat chronological sequence. Augustine writes as a saved sinner, selectively tracing his wanderings in the ways of God.

The book contains stretches of tough theological questioning interspersed with passages of moving tenderness and beauty. At times it echoes the rhythms of the Psalms, almost poetic in its lyricism. Above all it aims to draw others to contemplate in wonder the divine love that would not let Augustine go.

Reviewed by David F. Wright, professor of Patristic and Reformed Christianity at the University of Edinburgh.

In Print

In this excerpt from Book III, Monica has just dreamed that she and Augustine were standing together in fellowship with the divine.

How should she have had this dream unless Your ears had heard her heart, O Good Omnipotent, You who have such care for each one of us as if You had care for him alone, and such care for all as if we were all but one person?

And the same must have been the reason for this too: that when she had told me her vision and I tried to interpret it to mean that she must not despair of one day being as I was, she answered without an instant’s hesitation: “No. For it was not said to me where he is, you are, but where you are, he is.”

I confess to You, O Lord, that if I remember aright—and I have often spoken of it since—I was more deeply moved by that answer which You gave through my mother—in that she was not disturbed by the false plausibility of my interpretation and so quickly saw what was to be seen (which I certainly had not seen until she said it)—than by the dream itself: by which the joy that was to come to that holy woman so long after was foretold so long before for the relief of her present anguish.

Nine years were to follow in which I lay tossing in the mud of that deep pit and the more heavily. All that time this chaste, god-fearing and sober widow—for such You love—was all the more cheered up with hope. Yet she did not relax her weeping and mourning. She did not cease to pray at every hour and bewail me to You, and her prayers found entry into Your sight. But for all that You allowed me still to toss helplessly in that darkness.

One other answer I remember You gave her in that time. Many such things I pass over, because I am hastening on to the matters which I am more urgently pressed to confess to You, and many I have simply forgotten. But You gave her another assurance by the mouth of Your priest, a certain bishop reared up in the Church and well grounded in Your Scriptures. My mother asked him in his kindness to have some discussion with me, to refute my errors, to unteach me what was evil and teach me what was good, for he often did this when he found such people as it might profit.

He refused, rightly as I have realized since. He told her that I was as yet not ripe for teaching because I was all puffed up with the newness of my heresy and had already upset a number of insufficiently skilled people with certain questions—as she had, in fact, told him.

“But,” said he, “let him alone. Only pray to the Lord for him: he will himself discover by reading what his error is and how great his impiety.”

The bishop went on to tell her that his mother had been seduced by the Manichees so that as a small child he had been given over to them; and he had not only read practically all their books but had also copied them out; and had found out for himself, with no need for anyone to argue or convince him, that he must leave the sect. And he had left it. When he had told her this, my mother would not be satisfied but urged him with repeated entreaties and floods of tears to see me and discuss with me.

He, losing patience, said: “Go your way; as sure as you live, it is impossible that the son of these tears should perish.”

In the conversations we had afterwards, she often said that she had accepted this answer as if it had sounded from heaven.

Copyright © 2000 by the author or Christianity Today/Christian History magazine. Click here for reprint information on Christian History.