If you were conducting a poll and asked me if I read regularly to my children, I would say yes. I can name chapter books we have enjoyed with our older two: James and the Giant Peach, Pippi Longstocking, The Trumpet of the Swan, among others. I can point to our youngest child's favorite book of the moment—Kevin Henkes' Chrysanthemum.

Similarly, if you were to take a walk around our house, you would find lots and lots of books. Books in piles, books on shelves, books tucked into drawers and in boxes in the closets. Novels and picture books and chapter books and textbooks. Books from when we were children. Books bought at the local independent bookstore. Books purchased from Amazon. Lots and lots of books.

Reading is an integral part of our family. And yet—despite my assertion that we are a family of readers—many nights come and go without opening a book. We have a party to go to, or it is movie night, or the kids have a babysitter, or it just gets too late and the night slips away and the book sits on the bedstand unopened yet again. Plenty of afternoons come and go when the kids would happily snuggle up to my side and listen to me narrate a story, but there is just too much to do. Laundry and dishes and lunches for tomorrow and dinner for tonight.

So many distractions. So much to do. And, with the introduction of not only television but computers and other devices, so much that satisfies their need for stories without involving me.

For instance, one night last week I listened to NPR as I made dinner. Marilee (age 3) was watching Caillou on the computer. William (almost 6) had parked himself in front of Wild Kratts in the family room. Penny (age 8), my outlier, was reading Junie B. Jones. She can read to herself now, and she chooses books over tv a lot of the time. But that's only after hours and hours and hours of interaction with adults who read to her throughout her early years. That's only after I set intentional boundaries with screentime and actually stuck to them. With the younger two, less reading, more screens.

I suspect I'm not alone. Common Sense Media came out with a report last week about kids' and teens' reading in which it found that reading rates among adolescents "dropped precipitously." Only 17% of 17-year olds call themselves "daily readers." Similarly, fewer than half of all teenagers report that they read for pleasure. And as study after study has shown, and this report confirms, girls read more than boys on average, and white children tend to have higher reading skills than black and Latino children. Reading is in decline among our adolescents, which should put those of us with pre-adolescent children on the alert.

As I've thought about these reports, I've realized that I'm not worried that my kids won't learn to read. They will. They will read with proficiency, as will most of the children in America. But will they experience the pleasure of immersing themselves in a story that transplants them to another physical, historical, social or emotional world? Will they be amazed by the way a book can aid their imaginations? Will they look forward to reading a novel at the beach on vacation? I am not concerned about their abilities, but I worry they won't learn to love reading.

Parents face two barriers in passing along the joy of reading. There's the cultural barrier: reading competes with television shows, internet activities, video games, tablets, and smart phones, and just as we tend to choose fast food over home-cooked meals, we tend to gravitate toward the easier purveyor of content. There's also the educational barrier: as schools insist upon more and more nonfiction reading, kids begin to see books as means to the end of information gathering rather than an end in and of themselves. But I have to believe that we parents can do something to give the gift of reading to our children.

First, we can be readers ourselves. Kids notice us and imitate us, now and in the future. As the National Endowment for the Arts reported a decade ago, the most important predictor of whether kids grow up to be readers is having parents who read. (Note, I didn't say parents who read to their children, just parents who read.)

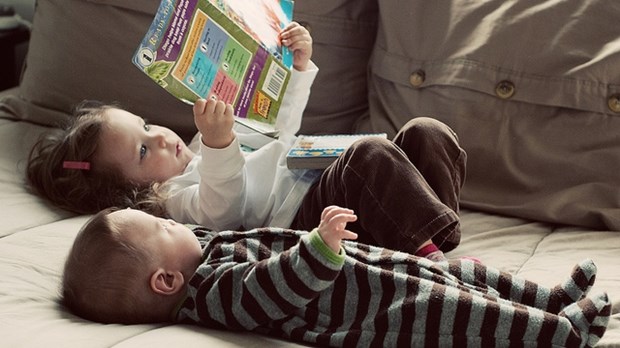

Second, we can read to our kids. Our children will rarely stumble into reading on their own. It will only happen if we commit to read with them, if we not only pass along the skills but the delight of immersing ourselves in a book. The pleasure of sharing an imaginative world, of relating to characters together, of learning new words, of wondering what might happen next.

Third, we can use technology to our advantage—audio books in the car, books using the Kindle App on the iPad, promising kids that we can watch the movie after we've read the book.

Four, we can integrate books into our other activities. We can talk about the characters on the pages even when the pages aren't in front of us and help our children draw parallels between their everyday lives and the lives of the people on the pages before bedtime.

Finally, we can think about practical ways to read with our kids every day, even if it is only for five minutes at breakfast (a poem, a section from a devotional book, a few pages from a chapter book) or ten minutes before bed. When we are loving a new book, we tend to get upstairs earlier and bump baths and showers to the morning just to give ourselves a little more time with the story at hand.

There is no quick fix to the problem of adolescents and adults who don't read. But there are solutions we can offer our children. They take time and effort. And they offer a lifetime of joy.

Support our work. Subscribe to CT and get one year free.

Recent Posts

Four Ways to Help Your Child Love Reading

Four Ways to Help Your Child Love Reading

Four Ways to Help Your Child Love Reading

Four Ways to Help Your Child Love Reading