The Pyramids of Giza used to be in the middle of the desert. Eventually Cairo’s urban sprawl pushed right up to the Sphinx. The Citadel of Saladin towers over the city. The southern approach requires an overpass straddling the City of the Dead. In Tahrir Square, the Egyptian Museum and its famed mummies were overrun with the bedlam of a revolution.

Tourism has dropped dramatically since then, but intrepid travelers can hardly help notice the encroachment of squalor on the glories of antiquity.

What most miss is the reversal: A glory rising out of the garbage. To create it, 40 years ago one man had to literally trudge through a pigsty. Today it is simpler to reach the massive cave church complex in the Muqattam Mountains on the eastern edge of Cairo. But the journey still requires a pungent assault on the senses.

Women and children pick through 15,000 tons of the city’s collected refuse, sorting out recyclable waste from the biodegradables useful for wandering livestock. Men haul burlap trash bags twice their size into garbage trucks poised to tip from overfill. Crude tattoos of St. George or a crucified Jesus adorn the arms of many a teenager. Pictures of Pope Shenouda and the Virgin Mary hang from open stalls filled with plastic bottles or corrugated cardboard.

This is the community of the Zabaleen, Garbage City, known officially as Manshiat Nasser. In 1969, the governor of Cairo created the slum by relocating the mostly Coptic Christian trash pickers to the base of the mountain, where they could keep their pigs in peace. The half-mile ascent is traversable by car, but the narrow street is made treacherous by potholes and the tight squeeze of donkey carts.

But arrival provides ample reward. At the top of the hill there is a sharp turn to the right before a final incline through a gate. A short 200-foot path gives an overlook of the slum below, and then the unexpected appears.

Carved into the rock face of the mountain is Jesus the Pantocrator, seated upon his throne, surrounded by four trumpet-blowing angels. In Arabic and English the inscription declares, “See the Son of Man coming in the clouds with great power and glory.” Gone is any trace of garbage.

This is but one of the many carvings at the Monastery of St. Simon the Tanner. The imposing cliff also bears images of the Ten Commandments, a scene from the Nativity, and the Arabic verse most dear to Coptic Christians, “Blessed be Egypt, my people.” Pummeled by images of poverty only a few minutes earlier, one can almost believe it is true.

It almost wasn’t.

By 1974, the community of Manshiat Nasser had grown to about 14,000 Copts, living without electricity, plumbing, or church. Alcoholism was rampant. Crime was common. A reluctant Orthodox layman was asked to visit with an eye toward ministry, and like Jonah, ran in the opposite direction.

But God’s tug held, and as it was for Jonah, the call was confirmed with a miraculous sign. One day Farahat Ibrahim was walking in the area, feeling overwhelmed. “Lord, I'm just a drop in the ocean,” he prayed. “There are many people here and they are very hard and wild. What do you want from me?”

At that moment, the wind picked up and blew the garbage all around him. Falling at his feet was one piece of paper in particular—a scrap from an Arabic Bible, which he has kept to this day. “I am with you, and no one is going to harm you,” he read from Acts 18, “because I have many people in this city.”

Ibrahim bought a pair of boots and a flashlight, and trudged out in visitation to his unreceptive adopted flock. One man attacked him with a knife. Another hid in the pigsty. But in an abandoned cave above the slum, in a tin hut with a reed roof, nine people attended the first church service on April 13.

Today this cave seats 20,000, the largest church capacity in the Middle East.

As the visitor passes the rock face full of carvings, a lone boulder offers the chiseled reminder, “If they keep quiet, the stones will cry out.” Turning left on Thursday nights, it is clear there is no need for the prophecy.

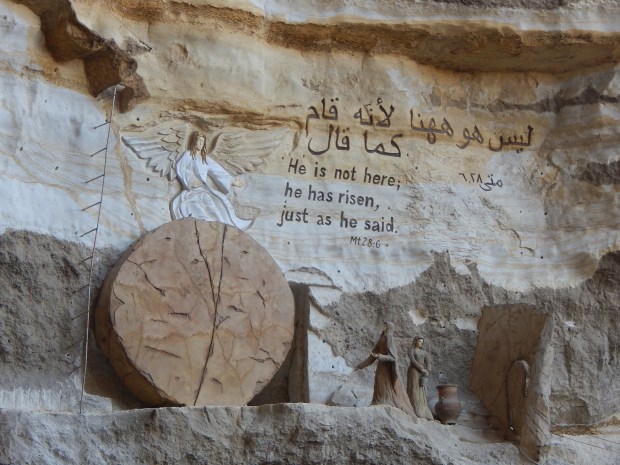

Descending a slight tunneled slope for about 20 yards, the visitor exits into the benches at the midpoint of a massive amphitheater. Across the sanctuary, an angel sits on the rolled-away stone, as two statuettes contemplate an empty tomb carved into the cave wall.

Above, a stadium-worthy projection screen makes the matchbox-sized priest visible to worshippers in the nosebleeds. Average attendance fills the lower section with around 4,000. But on November 11, 2011, an estimated 40,000 overflowed through the entire monastery. All Egypt’s Christians were invited to pray for their nation, shaken by the tumult of revolution and Islamist ascendency. “Jesus!” they shouted, at the top of their lungs.

Ordained as Father Simon in 1978, Ibrahim’s preaching, the praise and worship, and the weekly exorcisms nearly make the mountain tremble.

A thousand years earlier, according to Coptic lore, his namesake succeeded.

In AD 979, the Fatimid Caliph al-Mu’iz issued a challenge to the 62nd Patriarch of Alexandria, Pope Abram ibn Zaraa. The Christians were threatened with great calamity unless Abram could demonstrate faith as small as a mustard seed, and cause the mountain to move.

Troubled, Abram called for a three-day fast and a vision led him to Simon the Tanner, a simple man known for his piety. Quietly arranging for Simon to stand and pray behind him, the pope led the Elijah-like confrontation as Muqattam lifted from its base and the sun shone in the gap between elevated rock and astounded earth. Simon humbly disappeared into the crowd.

The startled caliph thereafter allowed a church building spree, and the modern Fr. Simon has imitated. The complex now hosts six sanctuaries and church halls built into the mountain’s caves. The one transformed into the Church of Pope Abram used to be a Zabaleen trash heap.

Meanwhile the slum is a little less slum-like. Six churches have been planted and serve the poor. Patmos Hospital serves the sick. Ninety percent of all trash gets recycled, as NGOs market creatively designed garbage-turned-crafts.

The 2009 documentary Garbage Dreams chronicles the life of the community with all its dignity. Last year, they helped Mona Gaballah become the first ever Coptic woman individually elected to parliament. And last month, the Tunisian-French artist eL Seed turned 50 gritty buildings into a calligraphic mural. It quotes from the third-century Coptic bishop St. Athanasius, “If one wants to see the light of the sun, he must wipe his eyes.” It is fitting for the context and designed to be visible only from the monastery.

But technically speaking, this is a misnomer. Housing no monks, the “monastery” is so named by the residents in appreciation for their sanctuary. As they leave it behind to return to their holy drudgery, it offers one last encouragement as they peer over the cliff at their gray cement skyline of partially completed buildings.

“Your enemy the devil prowls as a roaring lion,” reads the trail of last inscriptions. “Whatever happens, conduct yourself in a manner worthy of the gospel of Christ.”

It is this gospel that carved glory out of garbage, working itself beyond the neighborhoods of Cairo.

Jayson Casper regularly reports on the Mideast and North Africa for Christianity Today. He profiled missionary Ramon Llull for issue 30 of The Behemoth.