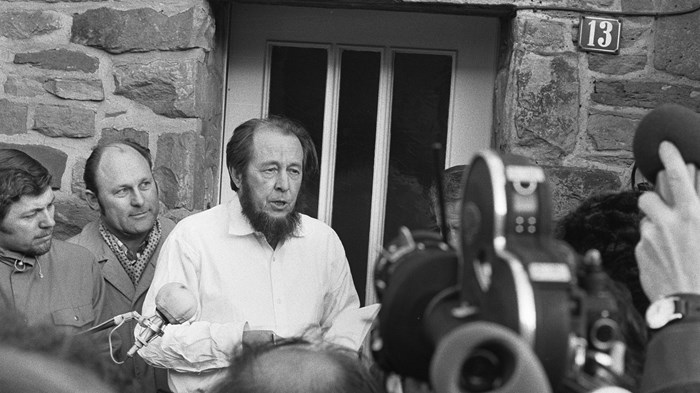

A high school teacher in his hovel far from home spends every spare minute writing—and then burying the manuscripts in jars. Who could have guessed that he was changing history? A Soviet-era joke set in the future has a teacher asking who Soviet president Leonid Brezhnev was and a schoolgirl replying, "Wasn't he some insignificant politician in the age of Solzhenitsyn?"

As a boy, Alexandr Solzhenitsyn planned to find fame through commemorating the glories of the Bolshevik Revolution. But as an artillery captain, he privately criticized Stalin and got packed off to eight years in the prison camps. There, the loyal Leninist encountered luminous religious believers and moved from the Marx of his schoolteachers to the Jesus of his Russian Orthodox forefathers: "God of the Universe!" he wrote, "I believe again! Though I renounced You, You were with me!"

After prison, Solzhenitsyn poured out once-unimaginable tales of the brutality of Soviet prison life. With One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich, the unknown author became lionized worldwide as a truth-telling freedom-fighter. A publishing event that Premier Nikita Khrushchev authorized as part of his de-Stalinization campaign looks, in retrospect, like the first crack in the Berlin Wall.

The Gulag Archipelago, a history of the Soviet concentration camps, prompted the Kremlin to ship the author westward in 1974.

At home, Solzhenitsyn had scolded the Soviet leaders for their attempted "eradication of Christian religion and morality" and for substituting an ideology with atheism as its "chief inspirational and emotional hub." But once in the West, he scolded Western elites for discarding "the moral heritage of Christian centuries with their great reserves of mercy and sacrifice" and for substituting "the proclaimed and practiced autonomy of man from any higher force above him."

Thus many Western intellectuals also turned against him (one headline bellowed, "Shut Up, Solzhenitsyn"). Despite his moderate political inclinations, critics pinned false labels on him: reactionary, chauvinist, monarchist, theocrat, even anti-Semite.

but right through every human heart." —Alexandr Solzhenitsyn

Solzhenitsyn replied, "They lie about me as if I were already dead," and complained, "Nobody ever gives any quotes."

Moving to Vermont and listening only to "the sad music of Russia," Solzhenitsyn fulfilled his boyhood plan with The Red Wheel, but now the Bolshevik Revolution was not celebrated but lamented. And "the main cause of the ruinous Revolution that swallowed up some sixty million of our people" was—as he had heard his elders starkly say—that "men have forgotten God." That forgetting is also "the principal trait of the entire twentieth century."

Today as the Cold War rapidly disappears from modern consciousness, Solzhenitsyn is less well-known. But he remains the indispensable witness to and keenest interpreter of the century's greatest intellectual and political conflict. New Yorker editor David Remnick calls him our age's "dominant writer" and says, "No writer that I can think of in history, really, was able to do so much through courage and literary skill to change the society they came from. And, to some extent, you have to credit the literary works of Alexandr Solzhenitsyn with helping to bring down the last empire on earth."

Edward E. Ericson, Jr., is a professor of English at Calvin College, Grand Rapids, Michigan, and author of Solzhenitsyn and the Modern World (Regnery Gateway, 1993).

Timeline

1917 Russian Revolution

1918 Alexandr Solzhenitsyn is born

1928 Joseph Stalin consolidates his power; first Five-Year Plan

1936-39 Stalin's great purge annihilates tens of thousands

1945 Solzhenitsyn arrested as a captain in the army; Soviets consolidate power in Eastern Europe, which begins the Cold War

1953 Solzhenitsyn released from prison camps and diagnosed with terminal cancer; Nikita Khrushchev takes power in U.S.S.R. upon Stalin's death

1962 Publishes One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich

1968 Publishes Cancer Ward and First Circle

1970 Awarded the Nobel Prize for literature

1973 Publishes first volume of Gulag Archipelago

1974 Exiled from his homeland

1988 Mikhail Gorbachev becomes U.S.S.R. president

1989 Berlin Wall dismantled

1994 Solzhenitsyn returns to Russia

You Are There

In his autobiographical The Oak and the Calf, Alexandr Solzhenitsyn recalls how he "wrote" in the camps, where writing was forbidden—and how vulnerable his work was.

In the camp, this meant committing my verse—many thousands of lines—to memory. To help me with this, I improvised decimal counting beads and, in transit prisons, broke up matchsticks and used the fragments as tallies. As I approached the end of my sentence, I grew more confident of my powers of memory, and began writing down and memorizing prose—dialogue at first, but then, bit by bit, whole densely written passages. … But more and more of my time—in the end as much as one week every month—went into the regular repetition of all I had memorized.

Then came exile, and right at the beginning of my exile, cancer. … In December [1953] the doctors—comrades in exile—confirmed that I had at most three weeks left.

All that I had memorized in the camps ran the risk of extinction together with the head that held it. This was a dreadful moment in my life: to die on the threshold of freedom, to see all I had written, all that gave meaning to my life thus far, about to perish with me. …

I hurriedly copied things out in tiny handwriting, rolled them, several pages at a time, into tight cylinders and squeezed these into a champagne bottle. I buried the bottle in my garden—and set off for Tashkent to meet the new year and to die. [In fact, he was treated and recovered completely.]

For more information on this topic, see:

Alexandr Solzhenitsyn

http://www.soc.pu.ru/gallery/solzhenitsyn/home.htmle

A World Split Apart: An Address by Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn

http://www.uncg.edu/~danford/solz.html

Copyright © 2000 by the author or Christianity Today/Christian History magazine.

Click here for reprint information on Christian History.

Support Our Work

Subscribe to CT for less than $4.25/month