(Second of two parts; click here to read part 1)

Giving to the parachurch The great unknown in calculating Christians’ charitable giving is the explosion of parachurch organizations. Research shows that churches are getting less money, proportionately. Are nonprofit organizations with more sophisticated fundraising methods getting more?

There are 600,000 nonprofit charitable organizations in the United States, and they appear to be growing fast. The number of those required to file returns with the IRS increased 78 percent between 1977 and 1990, while their revenues went up 227 percent in constant dollars. (Churches and organizations with less than $25,000 in income are not required to file.) By contrast, GNP increased only 52 percent. These nonprofits grew to almost 8 percent of the total American economy.

Church-growth expert David Barrett estimates that, worldwide, parachurch budgets are growing far faster than church budgets. He calculates that in 1900, parachurch organizations received $1 billion compared to $7 billion for churches. By 1970, the ratio had changed drastically—$20 billion for parachurches, $50 billion for churches. In 1996, by his estimates, parachurches had outgrown churches in total budget, $100 billion to $94 billion.

That analysis makes it sound as though the church is being submerged by a new species of institution. To some extent, that may be so. From another perspective, however, growth in parachurch giving is at least partly a return to nineteenth-century giving patterns when giving was more independent of denominations and “unified budgets.” Missionaries were often sent out by independent or semi-independent boards, such as the American Missionary Association or the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions. Roving agents visited churches, soliciting funds for a variety of causes. Appeals had to be vivid and urgent in this competitive environment—a fact that led to “donor fatigue” and calls for reform. Beginning in the 1920s, such particular appeals were replaced by unified budgeting, shifting from the concept of designated giving to more general denominational support. As a 1929 study put it, “The faithful few … who had come through the years to visualize specific situations and needs, now had their eyes turned to a ‘budget’ to be raised.”

The rise of parachurch giving may be simply a return to a more graphic, particular kind of appeal. Unlike the past, however, these appeals are not made in church. They are made through the mail or over the airwaves.

Uneasy about money Considering that Christians are primary contributors, you might expect enthusiasm for giving to bubble out of our churches. Not at all. Robert Lynn, a student of the history of American Christian fundraising, writes that “one of the most familiar refrains in the Protestant teachings about giving involves a mournful recital of statistics. … This lament centers upon the gap between what Protestants can and should give and what they actually contribute.” Lynn says there is no golden age we can return to, no time when Christians tithed unstintingly so that all that the church needed was provided. He quotes Dwight L. Moody saying, “Blessed are the money raisers, for in heaven they shall stand next to the martyrs.”

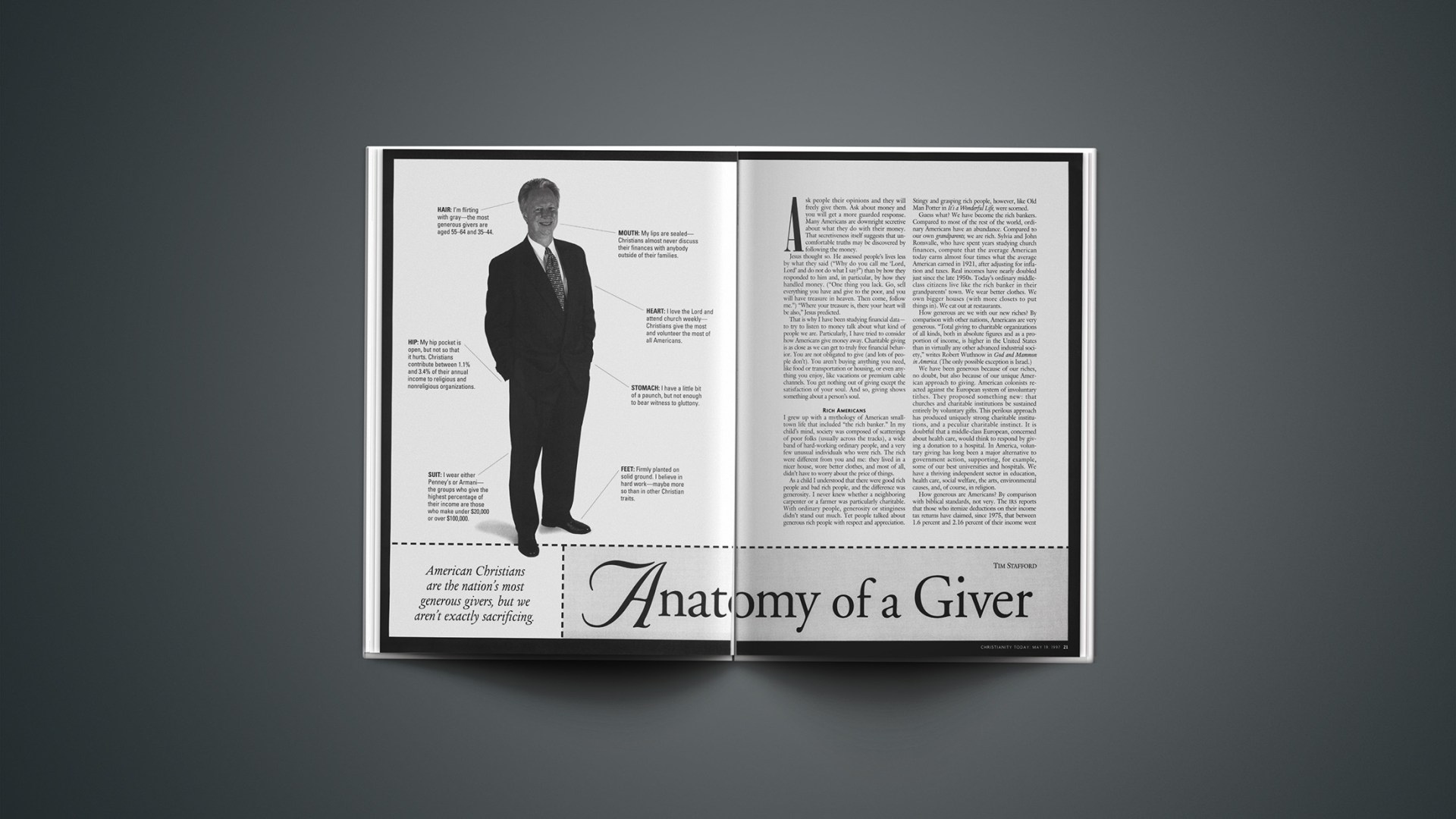

Many commentators note the quiet nervousness that seems to afflict fundraising in church circles today. Wuthnow found that Americans almost never discuss their finances with anybody outside their family: 82 percent had never discussed their income, 89 percent had not discussed their family budget, 92 percent had never discussed their giving to charities. And Christians were least likely to talk: about a quarter of those who rarely go to religious services say most of their friends have told them how much money they make, but only one in eight of those who go to church weekly says so. Furthermore, “the least likely group with whom conversations about personal finances had taken place were fellow church or synagogue members. … Nearly as unlikely were members of the clergy.” Notes Hugh Magers, “Episcopalians will tell you astounding things about their sexuality but not talk at all about their financial life.”

In all Protestant denominations, it is an unwritten law that the pastor not know what his church members contribute, even though most will admit that giving is an important clue to spiritual welfare.

“Some years ago,” Robert Lynn writes, “when our family moved to a new city, we found ourselves involved in that strange ritual known as ‘church shopping.’ Our search began in the fall, just at the opening of the season of ‘Stewardship Sundays.’ Several new friends urged us to ‘try’ their congregation but to stay away from visiting on that particular day. Even years later I can remember what one of them said: ‘It’s that time of year again. Don’t come on Stewardship Sunday, because you won’t get a sense of what our congregation is really like.’ “

Wuthnow notes that it bothers people “when religious organizations seem to be materialistic or seem to emphasize money too much. This means that religious organizations may have to find a way of appealing for money without actually talking about it.”

What appeals to people How silently, how silently, the wondrous gifts are given. We don’t talk about money, and don’t know how our best friends give. It is a mystery, to most of us.

Some people, though, talk about such matters quite freely. They are those who make their living raising money. They have a practical knowledge of what compels Christians to give, because they try all kinds of appeals and see what draws a response. Here are some factors they mention:

—Donors give to help the needy. Whether it is World Vision raising money for famine relief or the local rescue mission raising money for the homeless, Christian organizations find that people will give to causes offering tangible, immediate help. “Emergency feeding and sheltering is what works in rescue mission appeals,” said Tim Burgess of the Domain Group advertising agency. Burgess told me that getting money for job-training programs, for example, is much harder. And donors won’t give for evangelism unless it is part of a program to offer material help. “It’s very difficult to get an evangelism appeal to work,” he said, “especially with people under 50 years of age.”

—People give for measurable results. “My generation is more cynical,” Burgess says. “We want to know exactly what’s going to happen with our dollars.” People want it spelled out exactly what their money will do, and for whom. They do not give to solve the problem of child abuse in America. They give to support a program that meets every afternoon after school for the 38 at-risk children at Washington Elementary. Fundraisers suggested to me that lack of specificity explains why giving to churches has been flat or declining over the last several decades. Church appeals are usually for “the budget,” for “Christian education,” or for other generalities.

John and Sylvia Ronsvalle, from the organization Empty Tomb, find that in the 26 years from 1968 to 1993, the percentage of income church members gave to the church dropped from 2.48 percent to 2.09 percent. Evangelicals give considerably more than other Christians, the Ronsvalles say, but when they compared eight evangelical denominations (all NAE members) with eight mainline (NCC) denominations, they found that percentage giving in evangelical churches had dropped drastically—from 6.19 percent in 1968 to 4.27 percent in 1993. From 1985 to 1993, evangelical per-member contributions to their churches actually shrank slightly, in constant dollars—from $651 to $621. Evangelical churches have seemed immune to the financial difficulties afflicting mainline churches, but primarily because their numbers have been growing, the Ronsvalles suggest.

—People give to those they know and trust. Even though several fundraisers mentioned to me that evangelism is a hard sell, older, trusted organizations, such as the Billy Graham Evangelistic Association, continue to find willing supporters. Campus organizations like InterVarsity Christian Fellowship, and many missionary organizations, raise funds for the personal support of those who do evangelism. Supporters know these missionaries as individuals and trust them.

—People give to ministry they can be part of. They naturally support organizations they volunteer with. They don’t want simply to write checks; they want to participate in the cause through some other means as well. That is why so many Christian organizations offer their donors the opportunity to be part of a “President’s Council” or some other inner circle. They try to draw donors into a feeling (if not a reality) of true partnership.

Foreign missions face the problem that their work is “foreign,” far off and hard to identify with for most donors. The Ronsvalles quote one Protestant leader: “Sending money to missions is like dropping a stone down a deep well and never hearing it splash.”

The MARC survey of overseas missions shows that North American overseas mission personnel began decreasing in 1988 for the first time since the 1940s. Overall, mission funding has been mostly flat or declining slightly (in uninflated dollars) since 1979.

The Good Americans What do we learn about ourselves by following the money? In sum, who are we? I believe money says that Christians are the Good Americans.

Americans have always wanted to think of themselves as good, especially in contrast with decadent Europe and despotic Asia and Latin America. The WW II GI offering candy bars to children—he is the image of the Good American.

In fact, Americans are good in this way—generous, anxious to help by practical means, and confident that good can be done on a volunteer basis, if everybody will simply pitch in. Schools and libraries and public swimming pools can be built, hungry stomachs can be filled, orphans can find homes and families, wilderness can be preserved, all on a freewill, local basis. Most communities in America offer testimony to the practicality of this faith. Walk around town and see who built the library, the park, the community center. Visit the after-school tutoring center. See who is slinging hash for the homeless. You will find Good Americans.

Christians, it seems, are the quintessential Good Americans. Christians—not just nominal Christians, but believing, practicing Christians—are the backbone of virtually all charitable causes in America. They give most of the money, and they do a great deal of the work. By and large, they do it without bragging about it. That’s why it is surprising to learn that two-thirds of all charitable giving comes from active believers. The reason is not some media conspiracy to keep this truth silent. It is the modesty of the volunteers. They don’t usually make a point to say that they are giving or volunteering in the name of Christ. They don’t even necessarily think about it that way. They just do it, like the hero in a Frank Capra movie who acts from sheer decency and thinks he has done what anybody else would do.

Yet there is also a question about these Christian Good Americans: Are they more American than Christian? They believe in hard work and decency more than they believe in distinctly Christian behavior. They support evangelism only when it is done by someone they are absolutely sure won’t embarrass them. They give generously, but not sacrificially. As they have gotten wealthier they have been able to live better, but they give about the same, proportionately. Their affluence is indistinguishable from their neighbor’s. They are very practical about where their money goes: they want to keep tabs on it and ascertain that it is not being wasted. They think charity begins at home—they are less and less eager to send money overseas for a missionary cause that seems distant and never-ending. Above all, Good Americans don’t talk about money. Their money is their own, to do with what they like. It is a private matter, and they don’t want it talked about too much in church.

Is this the image of the Christian in the New Testament? I don’t believe so, for one reason above all else: the kingdom of God was a great deal more urgent than that. None of Jesus’ disciples, not the fishermen who threw in their family business to follow him, not Zacchaeus who offered to repay four times what he owed, not the early disciples who sold their land to support the Jerusalem church—none of them was careful. Because nothing was nearly so important, so breathtakingly urgent, as Jesus and his kingdom.

Such people are rare today. That’s what the money tells us.

Copyright © 1997 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.