“You know,” Chris Lewis says. “Fast girls.”

Lewis is not a longtime sex addict. He’s just an honest 14-year-old African American boy from a Dallas public school. Lewis doesn’t say whether he’s given in to these “fast girls.” If the most recent Centers for Disease Control’s Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance study is any indication, 29.9 percent of black boys engage in sex before they are 13 (compared to 14.2 percent of Hispanic boys and 7.5 percent of white boys), and 75.7 percent do so before they graduate from high school.

The girls sitting by Lewis, Monisha Randolph, 17, and Daketha Ward, 15, nod their heads knowingly, admitting that they also have felt the tug of Eros prematurely. Of African American girls, 11.4 percent engage in sex before 13, and 66.9 percent before they finish high school, the study says. Randolph and Ward also throw drugs, alcohol, and smoking in the mix of vices that allure them.

“If you’re around that stuff all the time, you’re tempted,” Randolph says.

But thanks to a smart program called the Love Clinic, kids like Lewis, Randolph, and Ward find it easier to elude these lures.

“You can tell some teens about abstinence from sun up to sun down, but they’re still going to have sex,” says Dr. Sheron C. Patterson. Preventing teenage pregnancy is one of the reasons why she founded the Love Clinic, an institute designed to foster healthy relationships among African Americans. In some ways, Patterson resembles Dr. Laura—if you add grace and love for Christ, and subtract the combativeness. Her realism dictates the way she goes about helping teens, many of whom were born to teenage mothers themselves.

“If they’re going to have sex, I don’t want them to have any children. I don’t want them to become parents, nor do I want them to catch AIDS,” Patterson says. So the Love Clinic youth leadership camps encourage teens to refrain from sex before marriage, but they also teach participants about birth control.

The Love Clinic youth camps work, and are worth imitating throughout the country. It’s hard to compute the work the Holy Spirit does in the hearts of the camp’s participants. But there is at least one objective way of measuring the program’s effectiveness. Of the camps 300 graduates, many of whom live in public housing projects, no one has become pregnant thus far, Patterson says.

Absent Fathers, Unwed Mothers

The pressures inner-city teens report are not race-specific. But statistics show, and African American leaders confirm, that forces plaguing black communities perpetuate the problems these youths face. One of them is the unraveling of African American families.“People become parents before they’re ready,” Patterson says. Most of these parents pass on their mistakes to their children. An especially painful influence is the general absence of black fathers, Patterson says. On any given day, one in three black men, ages 20 to 29, is in prison or jail, on probation, or on parole (compared to 12.3 percent of Latinos and 6.7 percent of whites).

Many of those who are not incarcerated deal drugs and belong to gangs. Seventy percent of African American babies are born to unwed mothers. A potent temptation to which many of these mothers surrender, especially in inner cities, is becoming codependent on men who lack stability, Patterson says. Consequently, many inner-city children watch, and imitate, the adults who never grew up.

Patterson launched the Love Clinic five years ago when she became fed up with a “community in shambles” she saw around her: a high divorce rate, teen pregnancies, “shacking up,” a growing number of sexually transmitted diseases, and gang-related and domestic violence.

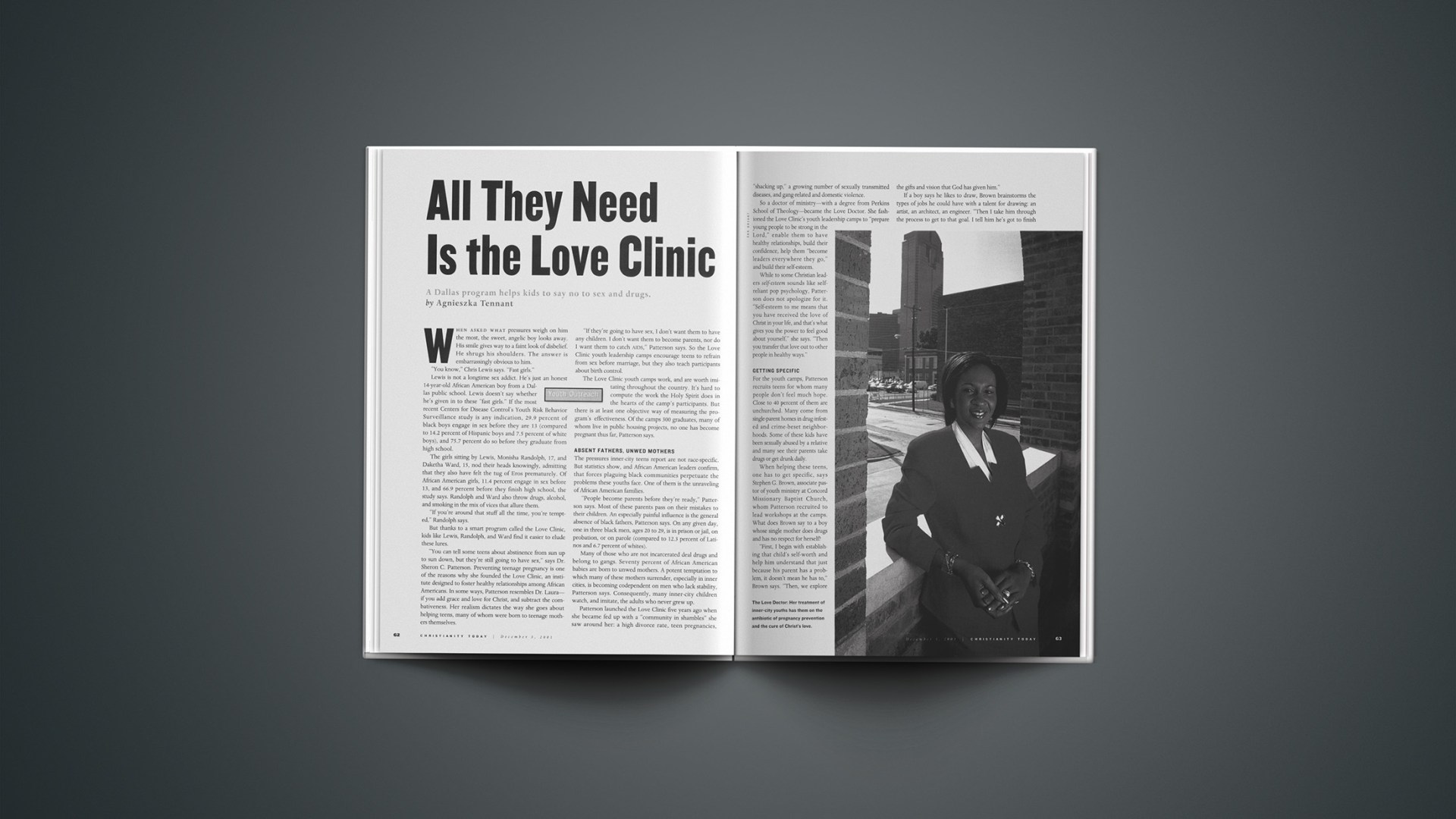

So a doctor of ministry—with a degree from Perkins School of Theology—became the Love Doctor. She fashioned the Love Clinic’s youth leadership camps to “prepare young people to be strong in the Lord,” enable them to have healthy relationships, build their confidence, help them “become leaders everywhere they go,” and build their self-esteem.

While to some Christian leaders self-esteem sounds like self-reliant pop psychology, Patterson does not apologize for it. “Self-esteem to me means that you have received the love of Christ in your life, and that’s what gives you the power to feel good about yourself,” she says. “Then you transfer that love out to other people in healthy ways.”

Getting Specific

For the youth camps, Patterson recruits teens for whom many people don’t feel much hope. Close to 40 percent of them are unchurched. Many come from single-parent homes in drug-infested and crime-beset neighborhoods. Some of these kids have been sexually abused by a relative and many see their parents take drugs or get drunk daily.When helping these teens, one has to get specific, says Stephen G. Brown, associate pastor of youth ministry at Concord Missionary Baptist Church, whom Patterson recruited to lead workshops at the camps. What does Brown say to a boy whose single mother does drugs and has no respect for herself?

“First, I begin with establishing that child’s self-worth and help him understand that just because his parent has a problem, it doesn’t mean he has to,” Brown says. “Then, we explore the gifts and vision that God has given him.”

If a boy says he likes to draw, Brown brainstorms the types of jobs he could have with a talent for drawing: an artist, an architect, an engineer. “Then I take him through the process to get to that goal. I tell him he’s got to finish high school and go to college,” he says. “Then we try to figure out how he can do this. He must see that he can rise above the destructive environment and be all God wants him to be.”

And what does Brown say to a young gang member?

“We start by defining what it means to be a good friend,” Brown says. “Gangs have a strong pull with kids who come from broken homes and are looking for a source of identity and sense of belonging. So I tell him that gang members are not good friends because his membership in the gang will most likely lead to his destruction. If he’s okay with it, then I tell him to stay in there. But if he’s not okay with it, I tell him that he’s got to make a decision to get out of the gang, and tell the gang leaders about it.”

To the kids who are afraid for their lives, he recommends relocation. “By relocation, I mean starting to hang out in different places, finding friends elsewhere, and sometimes even finding a new school.”

Patterson’s no-nonsense pragmatism, energy, sharp intellect, aplomb, and optimism fueled by her faith energize the countless ministries into which she pours herself. She pastors St. Paul United Methodist Church in the city’s arts district, hosts a popular radio show, has teamed up with other African American pastors to develop affordable housing, writes columns for the weekly Dallas Examiner, and leads Love Clinic seminars for kids, singles, and couples. Her gregarious personality has helped her get others excited about the Love Clinic.

Besides Patterson and Brown, the Love Clinic camp workshops are taught by registered nurses, a speaker from Mothers Against Teen Violence, a sex-education instructor, an aids-awareness teacher, and a speaker from a domestic-violence center.

Enthusiastic financial backing comes from two major institutions: State Farm Insurance and Charlton Methodist Hospital in Dallas. The sponsors see that the program works in preventing teenage pregnancy and addictions, Patterson says, so “nobody’s asking me to water down the Christian message.”

On average, at a camp with 30 to 40 students, including some 15 who are “extremely sexually active because of their environment,” about 20 students commit themselves to Christ and the majority make commitments to sexual purity, Brown says.

“They were not superficial commitments,” Brown says of a recent camp. “Some of the girls were crying, their hearts were broken, and I was able to see the power of Jesus Christ moving in their hearts.”

Lewis, Randolph, and Ward were among these students. “It will definitely be easier for me to say no to peer pressure,” Randolph says. “Because now I know that I have all the power of God behind me as well.”

Agnieszka Tennant is an assistant editor of Christianity Today.

Copyright © 2001 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.

Related Elsewhere

For Christianity Today sister publication, Leadership Journal, Sheron C. Patterson wrote on the Love Clinic’s outreach as part of a leadership symposium on reaching broken people. Previously, she wrote on church bullies and priming congregations for worship.

The Love Clinic Web site gives a good overview of the program and an explanation of this year’s objectives. Also, see the Love Clinic Online Magazine.

See the home page for St. Paul United Methodist Church.

Patterson writes a weekly column that appears in The Dallas Examiner. Additionally, she has authored books including: The Love Clinic: There is a Doctor in the House, I Want to Be Ready, and New Faith.