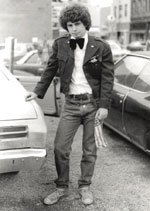

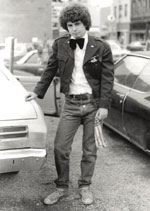

As a longtime fan of Daniel Johnston’s quirky music, filmmaker Jeff Feuerzeig thought it fitting to make a documentary about the brilliant-but-troubled musician.

The Devil and Daniel Johnston is an apt title for Feuerzeig’s film, depicting the wild roller coaster ride of an artist with bipolar disorder who has often battled his inner demons—sometimes quite literally.

Johnston, now 45, is a self-professed Christian who acknowledges Satan’s presence and the reality of spiritual warfare, though his mental illness at times twisted those truths into bizarre manifestations that haunt him and his art—his music and his drawings. Today, Johnston lives with his parents, both in their 80s, who worry about what will happen to him after they die.

The documentary is an honest glimpse into the sometimes strange, often disturbed, and always churning mind of a creative wunderkind whose music has been covered by Pearl Jam, Zwan, Beck, and Wilco, and whose fans include Johnny Depp, David Bowie, Simpsons creator Matt Groening—and Jeff Feuerzeig.

Feuerzeig won Best Director at Sundance last year for The Devil and Daniel Johnston, which took more than four years to make. Much of that time was spent transcribing hundreds of audio cassettes on which Johnson documented much of his life—from his teenage arguments with his mom, to his undying love for a girl who never returned it, to his delusions that he was Casper the Friendly Ghost. Snippets from those tapes are played throughout the film, giving the viewer unprecedented “access” to the mind of a genius at work—sometimes in the surge of creativity, sometimes in the midst of a meltdown.

It’s a fascinating portrait of a tormented-yet-gentle soul, and a project that Feuerzeig was more than happy to discuss with Christianity Today Movies.

You wanted to make this film because you’re a longtime fan?

Jeff Feuerzeig: I’ve been a huge fan since ’85, of his music and his art. I simply thought his life and his journey through manic depression—you know, madness and creativity—was very cinematic. I thought it would be a great movie to tell his story.

How did it affect you personally? Did it make you even more of a fan?

Feuerzeig: I don’t think I could become more of a fan because I was and remain his biggest fan and champion. I believe very strongly that the music he created in ’81,’82, ’83, in his basement, when he was really young, is the most raw, unfiltered, beautiful emotion that’s been laid to tape. It’s unfiltered because of his manic depression. And his unrequited love songs are just different than anyone else’s. I’ve seen it touch people all over the world, and it keeps getting passed around.

Could you have made this film without all the audiotapes Daniel had made?

Feuerzeig: Absolutely not. One of the key reasons the film is unique is that Daniel essentially recorded his entire life on tape. It’s probably the first opportunity we’ve ever had to go on the complete journey of an artist through their own audio diaries. You couldn’t make a film on van Gogh like this; the material doesn’t exist.

Sound is much more important than picture, and Daniel takes us there in the moment on those tapes. When his manic depression hits and he has tingles in his fingers, well, he’s recording that. He recorded his telephone conversations; he recorded audio letters to friends, diaries, his mom yelling at him, family arguments. It’s all there on the tape. He recorded his own arrest at the Statue of Liberty when he drew hundreds of Christian fish throughout the staircase. That’s extraordinary.

I transcribed them all, and I assembled what we call an internal monologue, which is what really takes us throughout his life, from his point of view.

What’s the biggest thing you learned while making this film, whether it’s about Daniel, about mental illness, or about Christianity?

Feuerzeig: About Daniel, I learned that to him, everything is good. Like in music. For me, bands like Journey, REO Speedwagon and Kansas make my skin crawl. But Daniel is listening to those bands right next to the Beatles and Elvis Costello—and it’s all good to him. There’s no bad. It’s all just input to him.

As far as Christianity, I learned a great deal. I learned that The Church of Christ is a very hip church. It’s the only church I’ve ever been in where there’s not one Jesus or cross on the walls; there’s no symbolism. And the congregation sings the entire service together. Daniel comes out of that tradition, and he’s actually recorded a few of those songs from church—like Careless Soul, which is on his gospel album, titled 1990.

How would you describe Daniel’s faith today? Would he call himself a Christian?

Feuerzeig: Absolutely. His family and Daniel are fundamentalist, right-wing Christians. But I don’t blame his family, his parents, for not understanding him when he was a teenager. They didn’t understand having an artist in the basement. I think there are a lot of families who would tell their kid, “Maybe music and art should just be a hobby. Why don’t you just go get a job?”

When Daniel ran away and did drugs and sowed his oats—you know, sex, drugs and rock ‘n’ roll—I guess he was away from his faith at that point. But the Church of Christ saved him—that and his family’s faith have kept Daniel alive to this day. I believe his parents’ faith has given them the strength to do what they have done—still taking care of him today. They have a deep understanding of manic depression. They’re always up on new medicine, constantly searching for new meds for Daniel. He’s on a cocktail of five different things a day. His dad takes his blood sugar, pricks his finger, checks his blood every single day. His dad gives him his meds because Daniel won’t take his meds without his dad giving it to him. I think it’s incredible what they’ve done.

So where’s the Devil come into all of this?

Feuerzeig: For Daniel, it’s very unfortunate because the right-wing fundamentalism was definitely put in his head as a boy, and that made the Devil very, very real to Daniel. I’ve said that the Devil is just a metaphor for his manic depression in my film title. But when I asked Daniel and his family, they said no, the Devil is very real to them. So when Daniel thought he was a Christian warrior, and when he believed he was Casper the Friendly Ghost dressed all in white, he thought he was battling the Devil.

He threw an old lady from church out a second-story window, and she broke both her ankles. He thought he was doing an exorcism. He believed he was ridding her of Satan. He thought he had done a good thing. So I think right-wing fundamentalism mixed with manic depression is a very heady cocktail. The results speak for themselves.

If you look at our movie poster and all the art Daniel has drawn, he was always fighting Satan. He called it the eternal battle. I am not sure he was ever aligned with Satan, but I do believe that he felt that Satan was pulling his strings.

The end of the film shows Daniel doing some kind of bizarre dancing, leaving the viewer with this observation that he’s still just a child out of touch with reality.

Feuerzeig: Daniel is, to quote his own dad, in arrested development. He stopped developing after the age of 12. He’s stuck in time, essentially in high school. The same things that he did in high school are what he does today—creating art, listening to Beatles bootlegs, no responsibilities, can’t take care of himself.

But, at the same time, intellectually, he’s always the smartest person in the room. He’s actually quite brilliant. He can have fascinating conversations about the history of animation, the original King Kong, the movie Schindler’s List, the Beatles—things he’s obsessed with. He can discuss Kurt Vonnegut. He’s very well read.

That dance at the end of the movie was actually a gift he did for me one night. It was basically an interpretive dance of his entire life. He does the propeller, which is the plane spinning out of control [an incident in a private plane with his dad, a pilot, in which a delusional Daniel almost got them both killed]. He does the straightjacket dance—like dance crazes from the ’50s. He does the Jackie Gleason to show his comedic side.

We were having a great time that night, about three in the morning, and I think it’s the best piece of film I’ve ever shot, and I think it symbolizes his whole life.

It’s compelling footage. You can’t say, “It’s just the closing credits, I’m out of here.”

Feuerzeig: No, it’s intentionally there for that reason. It’s there to tell you that Daniel Johnston is not out of the woods. He’s not well and he never will be well. But he’s an incredible artist and he’s put a lot of love and goodness out into the world, and he moves people to tears with his art. His song, “True Love Will Find You in the End,” is a masterpiece, one of the most beautiful love songs ever written. I’ve cried to it. That’s the reason people listen to Dan Johnston and look at his art.

The film includes very little interview time with Daniel today. Why?

Feuerzeig: Daniel and I did hours and hours of interviews, but because he’s so medicated, his interviews are not very good. He’s not able to really tell those stories. He doesn’t remember his old song lyrics. He’s just not able to go there. So those interviews were useless. But I also believe it makes it a much stronger film, because he was an enigma. I spent four and a half years with the guy, and I don’t know him any better than when I started.

A relationship is a two-way street, and Daniel can’t meet you half way down the street. So I’ve always thought of Daniel Johnston as an enigma that I’ve only known through his art and music. And I believe that’s the best way to know and appreciate him. It tends to keep him at arm’s length. Everyone wants to hug Casper, but he can’t really hug you back—but he can through the songs and the art.

What do you want people to get out of this film? A better understanding of this mental illness?

Feuerzeig: Right, no question.

What else?

Feuerzeig: Quite a few things. From a Christian point of view, these people, their faith is right there on the screen. Whatever your faith may be, faith is powerful. I’m a Jew and I think people have a faith that can give you strength and get you through some really tough times. It certainly it worked for this family.

As far as an artist and a musician, I believe that Daniel Johnston is one of the great artists that has ever lived. I’ve seen the power of his music and art touch people, and it continues to touch people and spread all around the world. He really deeply touched me and affected my life in a positive way. It has been an incredible journey going on this particular artist’s trip, and I think that’s what a great artist can do for people.

The Devil and Daniel Johnston is showing in limited release; for a list of theaters, check the official website.

Copyright © 2006 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.