It’s a warm and hazy day, and Frank and I are at our sons’ Little League practice, watching baseball but talking football. Nothing could be more typical of metro Pittsburgh in June. The Pirates, at 10 games below .500, are ambling toward their 15th straight losing season. The Steelers’ training camp starts in six weeks. Hallelujah.

Frank knows football, and certainly knows western Pennsylvania football. He is Frank Namath, nephew of the man who some 40 years ago made our steel town, Beaver Falls, almost a household name. When “Uncle Joey” got big, Frank tells me, his mother had to move out of town and into a tiny house on a hill that overlooks it. Strangers from all over the place had been besieging her, gawking, poking, prodding. She, blue collar through and through, found herself suddenly the mother of an icon—presumably no easy thing. Especially here.

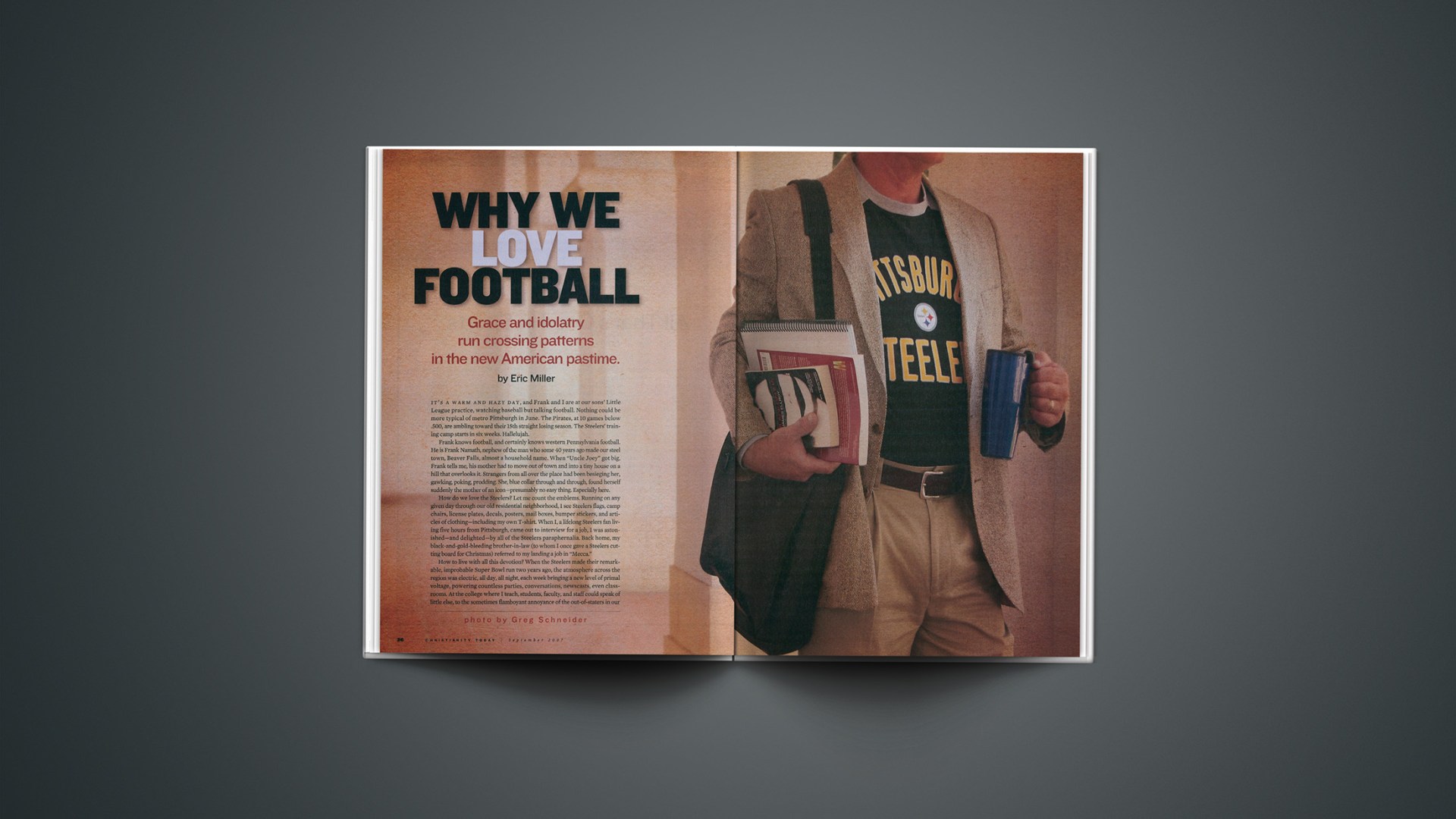

How do we love the Steelers? Let me count the emblems. Running on any given day through our old residential neighborhood, I see Steelers flags, camp chairs, license plates, decals, posters, mail boxes, bumper stickers, and articles of clothing—including my own T-shirt. When I, a lifelong Steelers fan living five hours from Pittsburgh, came out to interview for a job, I was astonished—and delighted—by all of the Steelers paraphernalia. Back home, my black-and-gold-bleeding brother-in-law (to whom I once gave a Steelers cutting board for Christmas) referred to my landing a job in “Mecca.”

How to live with all this devotion? When the Steelers made their remarkable, improbable Super Bowl run two years ago, the atmosphere across the region was electric, all day, all night, each week bringing a new level of primal voltage, powering countless parties, conversations, newscasts, even classrooms. At the college where I teach, students, faculty, and staff could speak of little else, to the sometimes flamboyant annoyance of the out-of-staters in our midst. Two guys, one from Ohio, the other from Cyprus, shaved their heads in protest, not of the Steelers so much as their fans. That included me, I suppose: I wore my Steelers necktie on Mondays and my “replica jersey” on Fridays—Black-and-Gold Day citywide, all month, as Pittsburghers sported their truest colors in effusive display.

January was, you might say, unusually warm that year, the temperature rising as the mercury dropped. Musicians wrote and recorded dozens of Steelers songs, some of which were played on radio stations, made available through the internet, and danced to at clubs and bars. (“What is it about the Steelers’ success that makes people say, ‘Where’s my kazoo?'” quipped Pittsburgh Post-Gazette columnist Gene Collier.) When at last Super Bowl Sunday arrived, I was amused and charmed most by the elderly woman who wore into our staid two-century-old Presbyterian church a plastic Steelers vest and Steelers earrings, hobbling into her pew with a glimmer in her eye. How did the pastor make it through the sermon? It’s hard enough under ordinary circumstances to preach to restless pew-sitters, let alone when they’re wearing face paint, as the children in one family did.

The NFL Is Us

Few dimensions of our common life so totally capture the 21st century American zeitgeist as the National Football League. Perhaps none do.

Certainly no other sport does. Pit the Super Bowl against the World Series and what do you get? Youth versus age. The 21st century rocketing past the 20th. Something rising; another falling. A single “wardrobe malfunction” permeated public consciousness more fully than anything that’s happened at the World Series since Bill Mazeroski shocked the Yankees and the nation in 1960. (What’s that? You don’t know anything about Mazeroski’s home run that … ? Ahem.)

No, the phenomenon of professional football—with its relentless specialization, its inordinately complex “strategic planning,” its rapid assimilation of new technologies (Can anyone imagine Namath with a radio in his helmet? Can anyone picture Jim Thorpe in a helmet?), its rhythm of quick bursts and pregnant pauses, its gleaming sensuality of (safe!) violence and sex, its worship of the youthful body, its intense drive for the jolting climax—spits our way of life back at us in neat three-hour packages, Sunday after Sunday (and occasional Mondays and Thursdays). We watch football, and we see our world far more roundly than we ever see it on CNN. Many of us feel it as fully as we feel it anywhere. The NFL is us. No wonder we don face paint.

To the extent that there is a surging cult of pro football in our day, it is at least partially bound up in an elaborate form of self-worship—which, of course, the NFL feeds off of. Every cult—every culture—needs its symbols, its priests, its holy places, its icons, its laws, and its gods. The NFL attentively furnishes them all. To my left, as I write, lies atop a filing cabinet my Super Bowl XL “locker room hat,” with the word “Champions” emblazoned between the Steelers logo and the NFL logo. Is it by accident that the NFL logo is positioned above the Steelers logo? I doubt it. The placement is a subtle assertion of rule, authority, and might.

Former NFL player and cultural historian Michael Oriard vividly charts the league’s cultlike ascendance in his illuminating new book, Brand NFL: Making and Selling America’s Favorite Sport. Namath, it turns out, was “the best thing to happen to the NFL since television”—not due to his effect on the league’s role as custodian of the sport but rather on its development into a “multimedia entertainment business.” Just as the NFL was searching for ways to enlarge its place in American life, Namath’s celebrity in the late 1960s wed pro football to the emerging empire of hip in utterly memorable, if not always salubrious, ways. Not only Sports Illustrated, but Time, Life, Esquire, and Playboy felt compelled to regularly comment on the meaning of Namath, the person of Namath, the sheer fact of Namath. For his part, Namath, writes Oriard, became “the first athlete in any sport to be himself an advertisement for a lifestyle.” Who can forget—try as we might—Namath hocking pantyhose?

That persona led thousands right back to the game—the NFL’s game. For Christmas in 1974, my brother and I received presents we greeted with mighty portions of yuletide glee: official Namath helmets, shoulder pads, and jerseys! The long arm of the NFL, via its nascent NFL Properties division, was reaching into our hearts and imaginations, connecting boys to a league in transforming ways, spawning identities rooted in whatever vision of life suited its own vision for its future.

Here’s what I wonder: What kind of organization provides us with everything we want, from extraordinary spectacles to godlike athletes to dancing girls? And what kind of people accept such offerings?

‘An Altered State of Being’

These are dangerous questions, costly to ask. So we don’t.

But ask we must—if that troubling, first-century category “the world” and the older notion of “idolatry” are to have any contemporary meaning. What do these ancient words get at if not a people’s steady refusal of the true pathway to life and their accompanying preference for counterfeits?

We, of course, stray toward worldliness and idolatry as children veer toward a candy shop. Lured by longing, excited by taste, we’ll check out any old peep show that comes along (from gossip pages to Penthouse pics) and try anything that whispers our name (from new hair colors to new wives). “An altered state of being / it’s what everybody’s looking for,” croons singer-songwriter John Hiatt, and he’s dead-on. “Those who cling to worthless idols forfeit the grace that could be theirs,” warned a much earlier poet, the prophet Jonah (2:8). He, too, nailed our miserable condition, as we, in a cock-eyed quest for life, turn toward decay. Truly we are, of all creatures, most wretched.

Here’s the thing, though, about idolatry, and what makes it doubly—triply—dangerous in our time: It is big business. It always has been, of course, an ever reliable means of profit at the expense of the human soul. But in a time when unprecedented concentrations of human intelligence are dedicated to preying on our frailty with an ingenuity and cunning that must surely drive the Pentagon to envy, we’ve become playthings of the profiteers.

The record on this is clear: We are no match for their wiles. All too easily, often blindly, we let them have their way.

So we must ask of the NFL what we must ask of any entity with the ability to touch our souls and shape our lives: Does it have our best—and our children’s best—interests at heart? Is there good evidence that it even knows our best interests? More particularly, to what lengths will it go to create a wholly faithful, devoted congregation, er … “fan base”?

And we must ask ourselves: Should I be a part of it? Is it keeping me on the true way? Or luring me away?

A Richer Experience of Grace

Despite these critical cautions, idolatry and worldliness are not the whole story, not by a long shot. Evil exists only by corrupting that which is good, and in football there remains considerable good to be savored and preserved. Football, to put it differently, may lead not to the forfeiture of grace but to a richer experience of it. And like most experiences of grace, it involves people and takes root in a place. For me, that place is Pittsburgh.

Having lived here for eight years now, I sense more fully the region’s rhythms, the slow shifting of seasons and sports, each sport with its season, each season incomplete without its sports. The traditions surrounding high school football run especially deep, I’ve learned. In our introductory history class, I require students to write research papers and urge them to use local sources. It’s the world of football that many of the local kids turn to, rooting out the legends and stories, investigating and re-telling tales of yore. The most memorable papers recount the students’ own participation in rituals and rivalries that go back decades, often to the early 20th century.

These young researchers are, I think, laying hold of a way to keep faith with the world of their childhood. This world was, at its best, a place of grace, with football near to the heart of it. College, they uneasily sense, offers not a way to settle into what they know but a course that will shake them from it. The authors they read, the people they meet, the training they acquire: Much of it prepares them for departure from their homes—especially likely given the area’s declining economic fortunes in these post-industrial, post-local United States. In this uncertain climate, high school football feels like the ground itself. So they dig in.

This reflects an impulse, common here (and I suspect elsewhere), to view football as a pathway to that which matters. Football in western Pennsylvania consistently gives rise to an experience, however ephemeral and elusive, of roots, of renewal, of home—a long hoped-for reunion not just with friends and kin, but with life itself. “Behold, how good and pleasant it is when brothers dwell in unity!” is the way the Psalmist (133:1) put it.

There are regional realities at play, to be sure, along with the more common experiences of loyal fans anywhere. The New York Times writer Jere Longman describes Pittsburgh as an “appealing but frayed city of immigrants” for good reason. It’s an area frayed not just by sharp declines in jobs and population—a loss between 1970 and 1990 of 158,000 manufacturing jobs and 289,000 residents—but also by the immigrant experience itself, as traces of ethnic particularity, so unexpectedly soluble, soften. What’s left is blended into America’s dull mainstream sheen, youthful faces that register “cool” and “fun” and “work” but little more. The longing for that something more, though—and for something lost—builds and deepens and ends up whooshing into the already huge, ever enlarging world of football.

In the midst of the Steelers’ 2005 surge to the Super Bowl, one Pittsburgh expatriate, Hollywood writer and director David Hollander, described in the Post-Gazette his own Steelers-sparked moment of longing and renewal following a decisive season-saving victory against the Bears. After Steelers running back Jerome Bettis knocked Bears über-linebacker Brian Urlacher to the ground and charged into the end zone, Hollander wrote, “My boy looked at me with alarm and asked why Daddy had tears running down his face.” To his knowing readers—his true countrymen, as it were—he confessed, “It’s hard to explain to a kid being raised in Southern California the meaning of loving a team as much as any kid from Pittsburgh loves the Steelers.” His shot at an explanation strikes chords—grace chords: “We love our Steelers because, at their best, our Steelers love the game. We love our Steelers because they play with power and joy and clarity, through pain and age and sore knees. …,” In a rapidly fraying world, the Steelers, remarkably, “have remained the Steelers.”

This is why Vic Ketchman, formerly of Pittsburgh, now the senior editor of the Jacksonville Jaguars team website, describes the Steelers as “the team for all the ones who like the old things”—people who “don’t want fast food, who don’t want to live in a new bedroom community and pay association fees, who don’t want progress forced upon us.” “Pittsburgh is an old place,” he concludes. And the Steelers? They’re “like coming home.”

Progress and Paradox

It does amount to something of a paradox, this notion that anything connected to today’s NFL could possibly stand against what Ketchman bitterly calls “progress.” But judging by the history of Pittsburgh, football can indeed be an agent that binds us to a place, to family and friends, perhaps even to a noble ethic. These effects seem to me all the evidence one requires to conclude that grace, of a certain kind, has been here. Is here.

It doesn’t happen everywhere, and it doesn’t automatically continue where it does happen. The people of Pittsburgh are fortunate to have on their side a powerful local family, the Rooneys, who have owned and operated the team since patriarch Art Rooney bought the team for $2,500 in 1933. Holding doggedly to their ideals for sport and community amid the torrent of the past half-century, the Rooneys have sought, often with painful compromises, to foster a team that even in the financially driven maelstrom of professional sports is bound to its community, in body and spirit. Embodying fidelity, they have sought players and coaches who not only excel at the game but who also love Pittsburgh, “the tough, sweet city of workers,” in poet Maggie Anderson’s words.

These Pittsburghers love the team—and the Rooneys—right back. And in loving, they gain a taste of life—or, better, a rich sampling of a deeper, truer life. In a faith-starved world, in a land being slowly emptied of meaningful ritual and intimate human ties, they, like modern folk the world round, turn to sport as a means of participation in the friendship, the laughter, the play, and the joy that lie at the heart of any healthy and flourishing human world, a place of which God can say, “It is good.” In doing so, they become responsible bearers of traditions that make such vital experiences possible.

But football, for all the good it may bring to a people and a place (but not every people or place), is not the final good, whatever the pretensions of the NFL or its devotees. The spirit of truth must always check the spirit of the age. And, truth be told, in this age our spirits settle for way too little. Football, cell phones, vacations, careers: These tantalize with the promise of plenty, yet leave us hungry for more.

To the starving, a piece of bread looks like a meal. The healthy know that it’s not, that we in our deepest parts hunger and thirst for something more, and that if this hunger isn’t augmented by more nutritious fare, the suffering will, in some form, go on. More, much more, is needed for true health.

At its best, sport may lead us more fully into an experience of health, an experience of community, play, joy—all good gifts of the Creator. But this happens only if it is enfolded within a grander, richer participation in life, in which another set of rites and symbols and songs takes us more deeply into gratitude and grace, sourced in the Creator and centered on the Cross.

I describe, of course, the way of the church, the beautiful dance of God’s own family, whose existence in this age is centered on the hope of welcoming into its way hungry people, distressed people—yet people who, for whatever else they may yet lack, have already come to know grace in rich, concrete, and satisfying ways. Christians concerned to love their neighbors could do worse than to join them in the stands come fall, cheering for all they’re worth. Grace, after all, goes both ways and touches down in highly improbable fashion—even, I’m guessing, through face paint and cutting boards.

Eric Miller is associate professor of history at Geneva College.

Copyright © 2007 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.

Related Elsewhere:

“God on the Gridiron,” and “Sacramental Football” (from Re:generation Quarterly) also address idolatry in sports.

Play Ball is an occasional Christianity Today column that examines the relationship between sports and faith.