John Kruk never looked like much of an athlete. He was a first baseman for the Philadelphia Phillies in the late 1980s and early 1990s, but as a teammate put it, he looked like a guy who drove a beer truck. His many diets were never able to trim his belly—"Don't worry," he once said. "I can always put the weight back on. Quickly." Despite his poor physique and bad habits he was a consistently good hitter, and ended his career with a lifetime .300 batting average.

One time he was sitting in a restaurant, eating a big meal while downing a couple of beers and smoking a cigarette, when a woman approached his table. She recognized him but said she was shocked, because she thought that he should be in training and that a professional athlete should take better care of himself.

Kruk leaned back and said, "I ain't an athlete, lady, I'm a baseball player."

The story reminds me of another quote, this one from basketball hall of famer Charles Barkley. He was one of the most dominating power forwards of his day (1990s), who used his strength and aggressiveness to intimidate opponents. He had no patience for those who believed athletes should be role models for kids. "A million guys can dunk a basketball in jail," he once said. "Should they be role models?"

As we come to another Super Bowl, we Christians note that the leaders of each team are devout believers—Colin Kaepernick on the 49ers and Ray Lewis on the Ravens (see the related CT story). Like any group with a strong self-identity, we Christians are proud that members of our tribe are star players in this national extravaganza. Not unexpectedly, when Christians become prominent in athletics, we are tempted to turn them into role models. We want them, like the lady wanted of John Kruk, to be models of athleticism, and like Charles Barkley comments, to be models of morality, as well.

But I suspect Charles Barkley had it right. Even Christian athletes, in the end, make for poor moral role models.

Glorious athletes in action

Our desire to lift them up as models of athleticism, morality—and religion—goes way back. The ancient Olympics were not merely athletic events but also religious festivals. The games were dedicated to the Greek god Zeus, and over time, the site of the games, Olympia, became worship central for the god of thunder. It included one of the largest Doric temples in Greece, and a 42-foot statue, made of gold and ivory, which sat on the throne of the temple. It was one of the seven wonders of the ancient world.

As the ancient historian Strabo put it, the Olympian games were considered "the greatest games in the world." Indeed, they were the Super Bowls of the ancient world. While there were no commercials specially created for the event, artists would cast wondrous works of art to celebrate the games and the athleticism displayed there. The most well-known perhaps is Myron's Diskobolos, or Discus Thrower—a thrower frozen just before he unwinds and hurls the discus. His physique is a picture of athletic beauty, a combination of power and grace that every athlete (if not John Kruk!) strives for.

When we see that power and grace in the field of play—well, it is a thing of wonder. We're witnessing human glory (that glory that is just a little less than the angels—Psalm 8). When we witness such a sight, it's almost impossible not to hope that this same human being might be a specimen of excellence in other arenas. Thus is born in us the desire for the athlete to be a moral role model.

As a society, we know better. There may have been a time when the immoral escapades of athletes were discretely ignored by journalists, but that time is no more. What amazes us today is not to discover that an athlete is narcissistic, greedy, and selfish; a philanderer, a drug addict, or even a murderer. It's when we find one who appears humble and morally upright. Thus our culture's fascination with Tim Tebow—an "oddball" in today's athletic culture.

For Christians, such moments feel like vindication: See, Christianity does make a difference! And when we see a Christian winner on the field, we hope against hope that he is a moral winner in his life—a role model for our children, and maybe even for us.

If you're like me, you want to feel that way about the two devout Christian stars who will take the field this Sunday. But that's a stretch.

Take Ray Lewis, whom sports writer Frank Deford described like this,

He is not, shall we say, quite the exemplary family man, having sired six children with a variety of women. He was indicted for murder in the year 2000, turned state's evidence and pled guilty to obstruction of justice. And, of course, he can be a brutal player—witness the monstrous illegal monstrous hit he pummeled the Patriots' Aaron Hernandez with in the AFL championship.

Add to that the strong evidence, as reported in this week's Sports Illustrated, that he took a banned substance earlier this season, and you get the picture. Or I should say the lack of a picture of moral rectitude.

At first glance, Colin Kaepernick seems like a better candidate for a role model. He was raised in a Christian home, and has Scripture verses tattooed over his body. As he told former NFL star quarterback Kurt Warner, "My first tattoo was a scroll on my right arm, Psalm 18:39. … It's just my way of showing everybody that this is what I believe in."

Well, except that the verses on his body are not exactly testimonies to humility or the grace of Christ, but seem designed to inspire aggressive play. Psalm 18:39 reads, "You armed me with strength for battle; you humbled my adversaries before me." Another tattoo, from Psalm 27:3, reads "Though an army besiege me, my heart will not fear; though war break out against me, even then I will be confident."

These verses are, in fact, apt descriptions of how this guy plays: he's fearless, determined, bellicose (prone to sling out four-letter words at his opponents), and extremely competitive. Not that there's a problem with being competitive—well, except when it is driven by pride. And Kaepernick's case it is. As a recent cover story in Sports Illustrated put it,

The truth is, beneath the serene, smiling exterior, Kap is still upset. He's angry at the college coaches who didn't find him worthy of a scholarship; at the NFL teams that needed a quarterback and didn't draft him; at the San Francisco fans who preferred [former starter Alex] Smith.

Kaepernick says, "I had a lot to prove," explaining, "A lot of people doubted me and my ability to lead this time."

Well, that's understandable, but let's face it: it's a desire driven by the need to justify oneself before others. It's called pride, and it's one of the seven deadly sins—a sin that every one of us is very familiar with, no?

Signs of grace

This gives us a clue about what we should be looking for in our Christian athletes—nothing more, nor less, than we look for in ourselves: signs of God's grace.

The Christian athlete, like any athlete in top condition and training, is a picture of athletic grace, to be sure. We can glorify our Creator for giving some men and women such extraordinary abilities for us to behold. But beyond that, we're looking at typically weak, selfish, prideful people, subject to the same temptations that we succumb to. They carry about with them a body, however glorious for the moment, that is subject to decay, with a heart desperately wicked (Jer. 17:9). Scoundrels is another word to describe us. Sinners is the biblical word.

And yet. These scoundrels—like us—are the very objects of God's mercy. It is for such that Christ died. As he put it, he didn't come for the role models, but for those who have failed to be role models (Luke 5:32). The most wondrous things we're seeing on the field are not glorious athletes but graced sinners.

Any athlete who begins to imagine that he is, in fact, a role model, would be wise to remember Jesus' parable of the Role Model and the Scoundrel in Luke 18:

Two men went up into the megachurch to pray, one a Role Model, and the other a Scoundrel. The Role Model, standing by himself and yet in clear view of the ESPN cameras, prayed thus: "God, I thank you that I am not like other athletes—self-centered, adulterers, and drug addicts, or even like that Scoundrel. I work out twice a day, I give my all, on and off the field, to be an example to others." But the Scoundrel, standing far off away from the microphones, would not even lift up his eyes, but wept, saying, "God, be merciful to me, a scoundrel!"

Jesus seemed to think the latter was the real role model.

Might I suggest a line for our favorite Christian athletes to use when people want to make them into something they are not?

"Hey, I ain't no role model; I'm just a scoundrel. …"

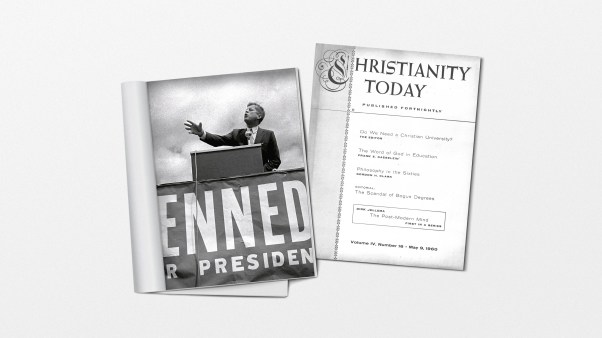

Mark Galli is editor of Christianity Today.