I've only been called by The Times UK once. It was late summer 2010, and they had Hawking: God Did Not Create Universe splashed across their front page. Stephen Hawking, the Cambridge physicist, had just written a book arguing that the cosmos had no designer, and the editors wanted a Christian response.

I had written a short book responding to Richard Dawkins's The God Delusion, but that was it. So when their religion correspondent rang me up out of the blue, and asked for some apologetics for tomorrow's front page, I wasn't as prepared as I might have been. I don't even remember what I said.

In the end, the paper got a last-minute comment from the Archbishop of Canterbury. (I didn't take it personally.) But reading Hawking's comments, and trying to improvise a decent response to them, reminded me how common it is to think that science and belief are at war. For Hawking, the only reason to believe in a creator is to explain the existence of the universe; when you find an explanation, the need for a creator disappears. For Dawkins, Darwinian evolution makes it "almost certain" that there is no God. At the same time, I know lots of Christians who argue the opposite: Since the Bible is true, you shouldn't believe in evolution, or the Big Bang, or whatever. From what I can tell, the battle lines are just as clear in America as they are here in Britain.

Dining with the Greats

The key issues in the ongoing debate about Christianity, evolution, and human origins can be summed up by three academics who used to watch me have dinner.

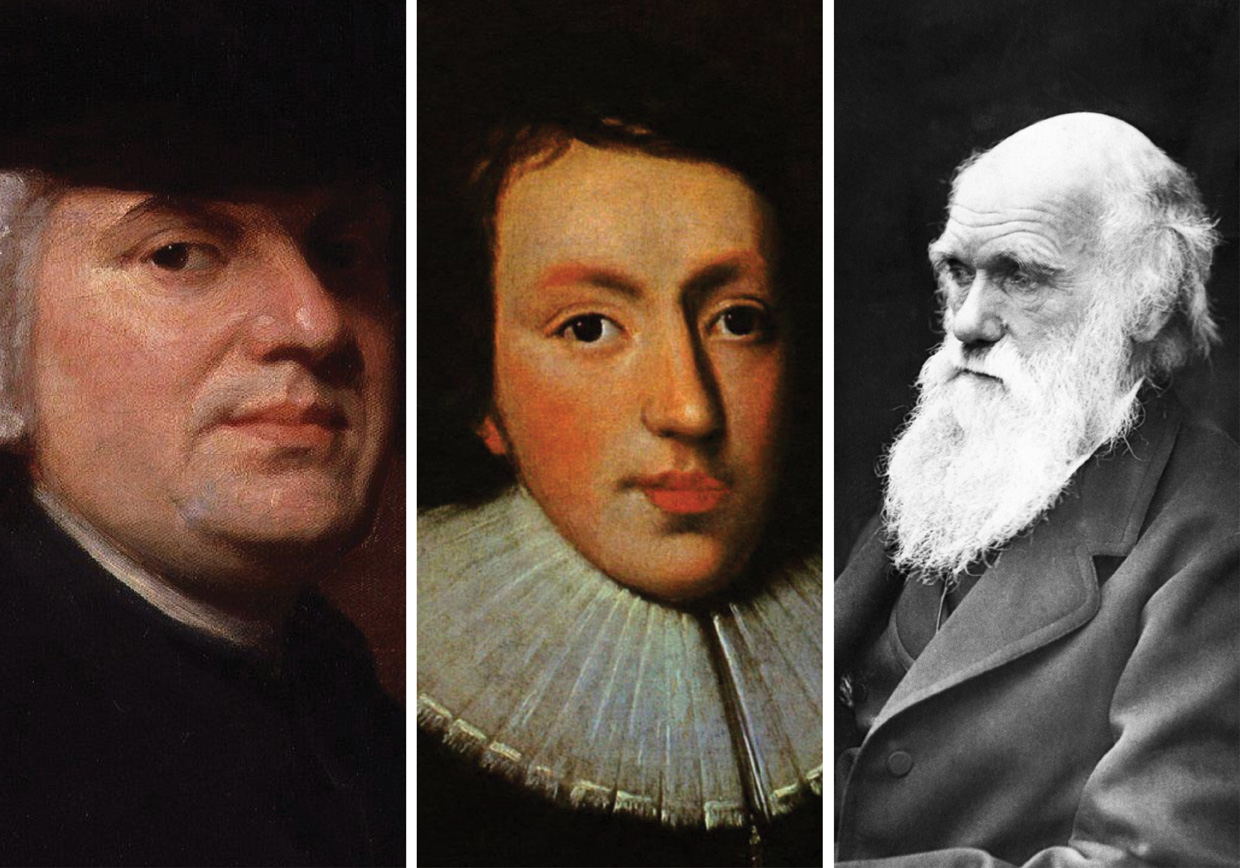

I attended Christ's College Cambridge. There, we would eat in a dark, oak-paneled dining room with distinguished alumni peering down at us out of their oil paintings. Three of them in particular—John Milton, William Paley, and Charles Darwin—changed the way we think about the Book of Genesis. They continue to represent three major ways of reading it.

John Milton is most famous for Paradise Lost. Composed in the mid–17th century, it is arguably the greatest poem written in English. It describes the beauty of Eden, the deceit of Adam and Eve, and the tragedy of the Fall. In the painting, Milton looked gray and slightly effeminate, but his poetry is bombastic. His account of the invasion of Earth by sin and Satan is dramatic, poetic, and highly theological. In Milton, Genesis is the central explanation for the existence of evil and death in the world.

William Paley, by contrast, was an 18th-century philosopher portrayed as a podgy, red-faced man donning a big black beret. Today he is best known for the watchmaker analogy for the existence of God. Nobody, Paley argued, would look at a watch and conclude it had not been designed. Similarly, it doesn't make sense to look at the world, in all its intricate detail, and conclude that nobody designed it; there must be a divine watchmaker. Genesis, then, is the story of how God designed and created all things. How else could the world have come about?

Enter Charles Darwin, whose oil painting is frightening: dark, stern, and disapproving, his face lined from years of staring at small creatures in boxes, with scowling eyebrows and an enormous Victorian beard. His scientific contribution, however, was enormous. Today his theory of evolution by natural selection is almost universally accepted in the academy, and has been broadly confirmed by studies in several fields. But for many, it clashes directly with the traditional reading of Genesis. Specifically, it seems to clash directly with the way that both Milton and Paley read Genesis, and how many Christians read Scripture today.

"If these walls could talk," we used to say. Imagine being able to get these great figures out of their oil paintings to have their own dinner conversation. Imagine the three discussing politics, or empire, or Genesis. Milton would be talking about the fall of a real human couple into sin and death. Paley would argue from the complexity of creation to design. And Darwin would respond that death has always been here (against Milton), and maybe that his theory displaced the need for design (against Paley). It's a shame the paintings can't come to life and chat, Harry Potter style.

Yet in many ways, a version of that conversation is taking place today in the West. There are those who side with Paley against Darwin: Life is designed, and therefore did not evolve. There are those who side with Darwin against Paley: Life evolved, and therefore is not designed. There are some for whom Darwin rules out Milton: Animals and humans have always died, so there was no Eden, no Adam, no Eve, and no fall. Then there are those for whom Milton rules out Darwin: Yes, there was, so no, they haven't. Still others agree with Darwin and Paley, but not Milton: Evolution is designed by God, but a literal fall never happened. Some even agree with Darwin and Milton but not Paley: Evolution happened, and a literal fall happened, but the design argument is just a God-of-the-gaps thing, and we shouldn't use it. And many proponents of each view get rather angry with people who hold a different one. It's all very confusing.

To make a complicated situation worse, there is a tiny minority of oddballs who think all three of them were essentially right, and who believe in the fall of Adam and Eve, the argument from design, and Darwinian evolution. Oddballs like me.

What If All Three Are Right?

You don't know me, of course. Apart from the fact that I went to Christ's College Cambridge, I could be anybody. So let me just say this, before going any further: I'm English, I'm a pastor and a writer, and I have two convictions that, in this context, are relevant.

First, I believe that the Scriptures, when interpreted properly with respect to their context, purpose, and genre, do not contain any mistakes. This is worth saying because, in my experience, people who hear that you believe in evolution often assume that it isn't true. Second, I believe in the general integrity and credibility of peer-reviewed journals, and the importance and value of experimental science. This is worth saying because, in my experience, people who hear you believe in a historical Adam and a historical fall often assume that this isn't true. The result, in my case, is that I have come to believe that Milton, Paley, and Darwin were all fundamentally right in what they argued. In my view, the argument from design, the historicity of the Fall, and the theory of evolution fit together.

The vast majority of people I know think these three are impossible to reconcile. Usually, that's because of death (Milton vs. Darwin), design (Darwin vs. Paley), or descent (Darwin vs. Milton), or perhaps a combination of the three. But I disagree. If we did somehow manage to get the boys from Christ's College out of their oil paintings, I believe they could resolve most of their differences.

Start with death. Milton, in the first few lines of Paradise Lost, describes his epic poem as the story

Of man's first disobedience,

and the fruit

Of that forbidden tree,

whose mortal taste

Brought death into the world,

and all our woe,

With loss of Eden,

till one greater Man

Restore us

In other words, for Milton, death came into the world through human disobedience. Darwin, on the other hand, saw death as having been in the world for millions of years before human beings even existed. So how on earth could they both be right?

Well, it depends what you mean by death. Darwin was talking about the physical death of plants and animals, and insisting that this had happened for a very long time. (From Genesis, by the way, we know that plants were eaten before the Fall, and there's no indication that animals were originally immortal either.) Milton, following Paul in Romans 5, was talking about the both physical and spiritual death of human beings, which, if you think about it, is also the focus of what God says in the story (Gen. 2:17; 3:19). So although it might look like Darwin and Milton were saying contradictory things about death, they weren't. They just thought about death differently.

The disagreement over design is even more heated these days. On one side, you have those who say that because complex life evolved, it wasn't designed. This is where Dawkins is coming from, along with the people who designed the Darwin fish. On the other side, there are those who argue that because complex life was designed, it cannot have evolved. They would argue that evolution presupposes a random process, and therefore is incompatible with design or a designer. The former quote Darwin, and the latter quote Paley. Again, it looks like the apologist and the biologist could not agree.

But things are not quite as they seem. One, physical causes do not rule out personal ones. That's why the discovery of hormones and chemicals in the brain has not led scientists to write books called The Love Delusion or Love Is Not Great or Unweaving the Spell: Love as a Natural Phenomenon. For another, God frequently designs things using processes that look very random, sometimes over a very long period of time. The Grand Canyon was formed by erosion that might look very random, but it was designed by God. The Rockies were formed by apparently arbitrary movements of the earth's crust, but they were still designed by God. So the use of long-term, apparently random processes does not rule out divine design.

Furthermore, if God is sovereign, then nothing in his world is random, even if it looks that way to us. (Just ask Ahab, who was killed by an arrow fired "at random," just after the prophet Micah had predicted it would happen, in 1 Kings 22:13–40.) And most important, Paley's argument still holds true for the origin of the cosmos, the fine-tuning of the universe's physical laws, and the beginning of information, life, and consciousness. Even if Darwin's theory was proved right in every detail, it wouldn't make evolution random, and it certainly wouldn't rule out design.

The third issue is the stickiest of all. For Milton, Adam and Eve were real people, created in the image of God: Adam from the dust of the earth, and Eve from the rib of the man. For Darwin, though, human beings share ancestry with other creatures. The apostle Paul, and Milton after him, clearly believed Adam was a historical figure. But modern genetics has added huge scientific weight to Darwin's view, through the study of pseudogenes, "jumping genes," retroviral insertions, and so on. So today, most of us either support Milton and reject Darwin: "We're all descended from Adam, and we're not descended from other creatures," or we support Darwin and disagree with Milton: "We are descended from other creatures, so Adam wasn't a historical person." The first leads to some big problems with science, and the second leads to some big problems with Scripture.

But here are a couple of observations that might help. There is no evidence to say that a pair of Neolithic farmers, formed directly by the hand of God in Mesopotamia, did not exist. There's no evidence to suggest that they weren't the first people, made in his image, with the soul-life of God breathed into them. There's no evidence to contradict the claim that they knew God, and were tempted, and sinned, and were exiled, and had children, and died. Not only that, but Genesis doesn't actually say that all human beings are biologically descended from Adam and Eve alone. The people Cain was scared of, and the woman he married, don't seem to be related to him. And if they weren't, then we don't actually know if they were created out of the dust of the earth, created out of creatures that already existed, or created in some other way.

So, I don't think Milton and Darwin are impossible to reconcile. In fact, I can't think of anything Milton (or Genesis) says about Adam and Eve that is contradicted by Darwinian evolution, as strange as that sounds.

Kindred Spirits Today

There may be some for whom all of this sounds rather obvious. John Stott, Derek Kidner, J. I. Packer, Tim Keller, and Francis Collins have all more or less taken the same approach. But there may be others for whom it sounds completely bonkers. For some, it will be too liberal (in accepting science too uncritically), and for others, it will be too conservative (in accepting Scripture too uncritically). I've been called both on this issue, and not always nicely.

For me, though, the study of origins—and, for that matter, the more important study of Scripture—involves going through exactly this sort of exercise. It means reading the text for what it is, asking the difficult questions, and then bringing together the brightest people to talk about them, pulling them out of their oil paintings if necessary. In the case of origins, it means integrating poetic, apologetic, and scientific approaches, and seeing how they shed light on the texts. And then, when we understand what Genesis is saying, it means submitting to the authority of the Word of God, and rejoicing in it.

One day, praise God, we will find out exactly what happened, and how much of what Milton, Paley, and Darwin said was actually true. I'll see you in the queue.

Andrew J. Wilson is the author of If God, Then What?: Wondering Aloud about Truth, Origins, and Redemption (InterVarsity) and blogs at ThinkTheology.co.uk. You can find him on Twitter @AJWTheology.