To-do lists written on pottery shards 2,600 years ago are causing some secular scholars to think the Bible was written years earlier than previously thought.

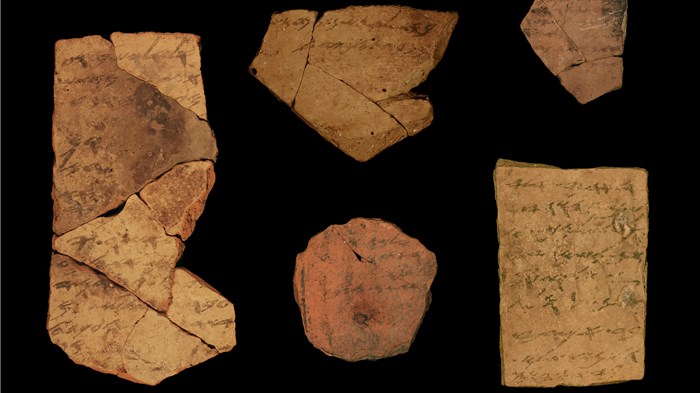

These ostraca, as inscriptions on pottery are called, were excavated half a century ago at the ancient fortress of Tel Arad in the Negev Desert near the Dead Sea. Sixteen of the ostraca were subjected to a high-tech analysis by Tel Aviv University researchers, who determined the ancient sticky notes were written at roughly the same time by six different individuals. Their findings were published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Based on that sample, the researchers concluded that literacy in the seventh century B.C. kingdom of Judah was more widespread than secular scholars have thought. And they are re-examining the widely held belief that the Hebrew Bible was compiled after the Israelites were exiled to Babylon in 586 B.C.

“What this research shows is that there were several people able to read and write in the fortress at Arad about the year 600 [B.C.],” said Alan Millard, an evangelical scholar and emeritus professor of Hebrew and ancient Semitic languages at the University of Liverpool. “That means they had learned from others, and their number suggests there were equal or greater numbers with those skills in larger towns like Jerusalem, Lachish, or Hebron.

“I have argued for years that there were a number of people able to read and write throughout the period of the kings of Israel and Judah,” he said, “and there is some evidence to support the contention that they could have been writing literary works like some of the biblical books.”

However, Millard was also cautious.

“The deduction that this research shows a ‘spread of literacy in late-monarchic Judah’ which ‘provides a possible stage setting for the compilation of literary works’ and therefore gives the background for the composition of Deuteronomy and Joshua-Kings depends, of course, on literary critical assumptions,” he said. “There are no comparable collections of ostraca from the ninth or eighth centuries B.C. which could be examined in the same way.”

Evangelical scholars such as Walter Kaiser Jr., president emeritus and Old Testament professor at Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary, point to numerous texts within the Bible itself that suggest writing was more widespread in biblical times than archaeology has been able to confirm so far.

One example is the story of Gideon, who had a score to settle with the leaders of Sukkoth. In Judges 8:14, he asks a youth of Sukkoth to write the names of the town’s elders. The young man wrote 77 names.

“The fact that a youth could be expected to do this says a lot about literacy 700 or more years prior to 600 B.C.,” said Kaiser.

Another example: treaty records of the Hittites from the 15th century B.C. are structurally similar to the book of Deuteronomy, while treaties from the sixth and seventh centuries B.C. are significantly different, he said.

“That supports the claim that Moses wrote these books,” said Kaiser.

Christopher Rollston, professor of Northwest Semitic languages at George Washington University, called the Tel Aviv University project “among the most innovative and important in the world.”

“The methodology is stunningly important,” wrote Rollston on his blog. “But I would wish to see more caution regarding their conclusions.”

The ostraca didn’t support the arguments about literacy in general, he said.

Like Kaiser, Rollston pointed to other work (including his own) that he believes indicates sufficient scribal support for Bible production as early as 800 B.C. Mainstream Bible scholars who look beyond the Bible for evidence are reluctant to go much earlier than that.

Overall, archaeology has been good to evangelicalism, Kaiser said.

“Biblical archaeology, especially in the 20th century, was one of the greatest witnesses to the historical points in the biblical text,” he said. “Not that we were able to demonstrate everything—far from that. But there were so many confirmations that there was a high probability that perhaps the whole text is demonstrating exactly what the Bible proclaims.”

Kaiser said he was glad to see the Tel Aviv team offer new perspectives on the old writing.

“They’re moving in the right direction,” he said. “I just say, ‘Keep going.’”

Support Our Work

Subscribe to CT for less than $4.25/month