In 1902 a black man named Alonzo Tucker was lynched from a bridge in the coastal town of Coos Bay, Oregon, a few hours south of my home. It is the only lynching on record in the state, and the limited known details were enough to catch my throat. Tucker had been accused of assaulting a white woman, and an angry mob had formed to take his life in the streets. He was jailed, partly to protect him from the crowds. But at some point, he panicked and somehow escaped, hiding for a night beneath some docks.

In the morning, a band of men found Tucker and shot him as he tried to run away. Tucker may have died from his wounds—no one knows for certain—but to make sure he was dead and to make a spectacle of the event, the crowd hung Tucker from the Fourth Street Bridge, right in the heart of that small Oregon coal-mining town.

I stumbled upon Tucker’s story while researching racial injustice in Oregon and couldn’t get it out of my mind. We had a family beach trip coming up, and I told my husband we needed to detour through Coos Bay to visit the site where Tucker died. He drove to the hardware store, bought some lumber, and made a large white cross to bring with us.

Once in town, I couldn’t find the Fourth Street Bridge. My husband dropped me at the local history museum and took our kids to play in a park. I awkwardly brought up the lynching with the man at the museum, who knew exactly what I was referring to. He gave me as much information as he had, making copies from local history books. I asked him if the museum would ever consider making an exhibit about Tucker, but the man shook his head sadly. “We just don’t have enough information” he said. “There isn’t even a single photo of Alonzo in existence.”

It turned out the bridge from which Tucker had hung no longer exists, consumed by shifting coastal topography. In its place is a relatively busy street next to the high school, a football field on one side and a baseball field on the other.

I rejoined my husband and kids at the park. I told him maybe we shouldn’t put up our memorial, that this was a stupid idea. But then in the park, I saw a large statue of a cross with a plaque underneath, a memorial to residents of the town who had fought and died in Vietnam.

Why did I think my own cross was stupid? Why did I falter in my plan to remember Tucker and acknowledge a dark day in Oregon’s history while a veterans’ monument seemed so acceptable? After all, memorials are a part of the American landscape. Less culturally obvious, I realized, are the criteria for selecting whom and what we memorialize.

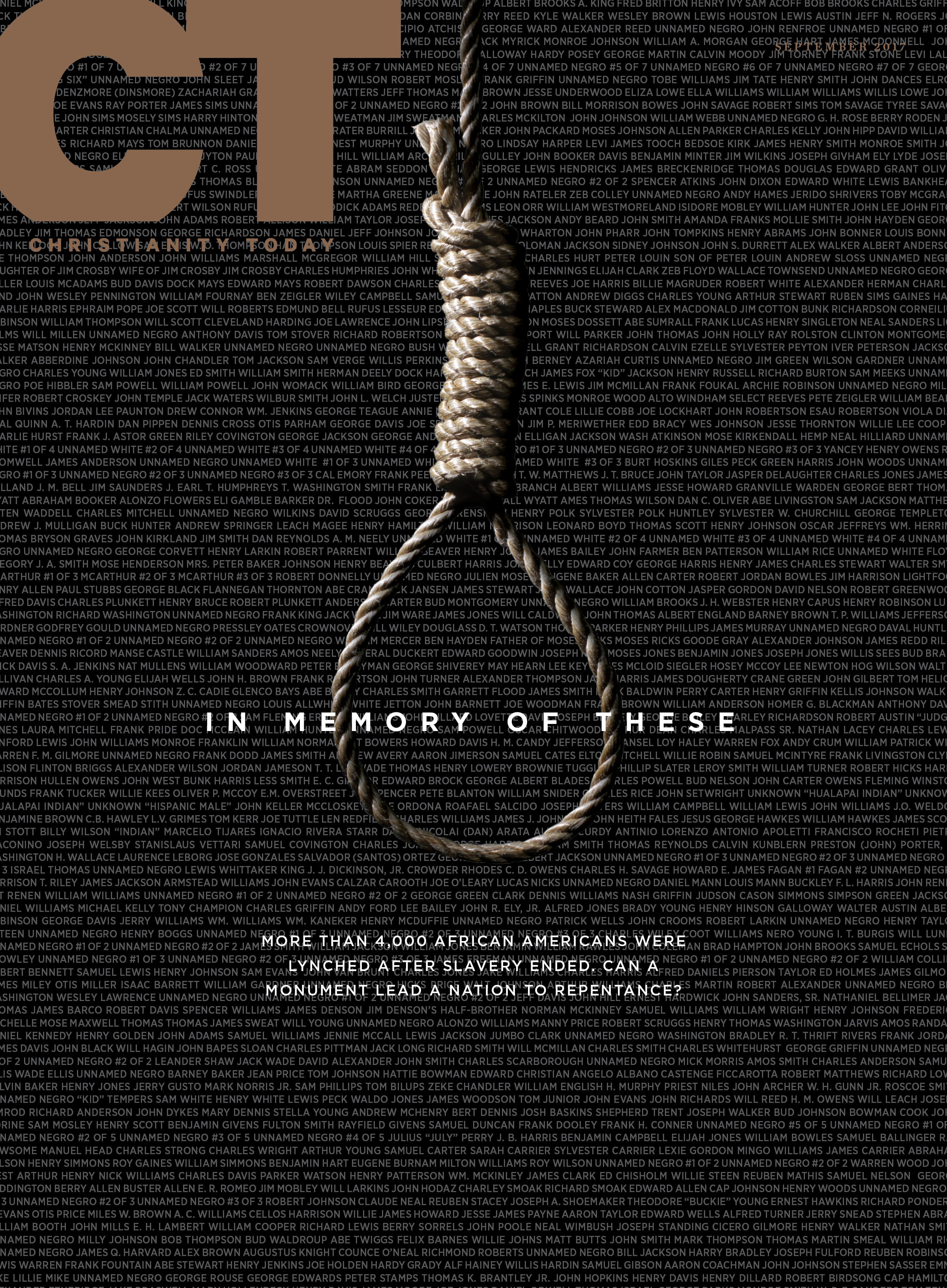

More than 4,000 African Americans were lynched between 1877 and the rise of the civil rights movement in the early 1950s. Lynching was a brutal public tactic for maintaining white supremacy, frequently used with the tacit blessing of government authorities. It was a part of my heritage I had never been taught, despite my homeschool community’s heavy focus on American history and despite brave efforts by activists like Ida B. Wells, perhaps the 19th century’s most famous anti-lynching voice, to draw attention to the epidemic.

Courtesy Krispin Mayfield

Courtesy Krispin MayfieldWe went ahead with our plan and drove to the high school. This wasn’t what I had envisioned, I thought, as a steady stream of cars drove past us. It was lunchtime, and there were students everywhere—hardly a place of contemplative silence and respect. I wrote “Alonzo Tucker 1902” on the large white plywood cross. My husband tried to hammer it into the ground next to a chainlink fence by the baseball field while I stayed in the car, safely hidden from any stares. He couldn’t get it to stay planted in the hard ground, and we hadn’t thought to bring anything to tie it to a fence, so he leaned it up against the chainlink and took a few pictures.

A police car drove by, and I felt a stab of fear—would we get in trouble for this? I told my husband to hurry up, and he hopped in the car. We drove off, and I was struck by the lack of ceremony. My kids cried in the backseat, and I gripped the steering wheel as we headed back up the coast, still looking over my shoulder to see if we would be stopped. I was surprised at how nervous I was and by how small our action felt. My husband reassured me that it was worth it, for our own sakes if nothing else.

We were starting, just barely, to understand the mysterious authority that we give memorials to determine which stories will be told through the generations and which will be forgotten. At a moment in May when debate was crescendoing on the opposite side of the country over the removal of Confederate monuments in New Orleans, we were starting to realize the subtle power memorials have over the sins of our past—the power either to hide them or to bring them into the light. I was starting to wonder at all the untold history we would rather forget. Of the collective sins we long the most to disregard, America’s tragic history of lynching might top the list. But what struck me on our journey was this: Buried sins cannot be repented of.

Learning to See the Sins

The memorial for Alonzo Tucker wasn’t my idea, not entirely.

A few months earlier, I had found myself in the offices of Bryan Stevenson and the advocacy group he started, the Equal Justice Initiative (EJI). Stevenson has worked for three decades as a lawyer, advocating for justice for those on death row and rising to national fame in part because of his best-selling memoir, Just Mercy. He’s become one of the most prominent voices for racial justice in the United States.

Stevenson, who grew up in the African Methodist Episcopal Church and directed the gospel choir at Eastern University before graduating from Harvard Law School, laces his public appearances with Scripture and says his faith is the backbone of his work. I wanted to see some of that work first hand.

We were starting to realize the subtle power memorials have over the sins of our past, the power either to hide them or to bring them into the light.

I was looking at a large wall completely covered by beautiful glass jars on wooden shelves. The jars were filled with dirt, shades of green and brown and gold and rust, stacked row upon row from the floor to the high ceiling. It seemed beautiful, until I took a closer look: Each jar bore a name and a location. Stevenson told us that each of the jars contained soil from a site of a confirmed lynching in the state of Alabama. That entire wall—all of those jars, all of those names—was still just a partial story of one state, a snapshot of a history I was never fully taught.

Stevenson began his education in black classrooms and watched as lawyers had to fight to desegregate his local school system. He is well aware that Americans are raised on widely differing versions of history. Which is why, after 30 years of pursuing fair and just treatment for incarcerated people in the criminal justice system, he is changing his strategy of combatting racial bias.

“A few years ago, I began to realize that the people who enforce the law are shaped by narratives; they are shaped by an understanding of history and their values and their responsiveness,” Stevenson said in an interview. “And with regard to race, I think we have done a very poor job in America of confronting our history.”

Stevenson became enamored with the idea of creating spaces for truth telling. “We don’t have many places in our country where you can have an honest experience with our history of slavery, and there are no spaces where you can have an honest experience with lynchings and racial terror,” he said. (There are outliers in unexpected places, such as a memorial in Duluth, Minnesota, honoring three black members of a traveling circus who were lynched there in 1920.)

So Stevenson decided to make one. Next summer, EJI will unveil a memorial where visitors will be confronted with large tablets hanging from a square structure, visual reminders of more than 800 counties where lynchings took place. The visual—so many markers engraved with so many names—will transform a hill overlooking downtown Montgomery, Alabama, into a place of mourning and remembrance, a place to lament and perhaps even to corporately confess.

The Memorial for Peace and Justice, as it will be called, will also encompass a field spreading next to the main structure. In that field, each hanging tablet will have an identical twin resting on the ground, invoking an eerie similarity to headstones. These markers will be for the counties themselves to collect. Stevenson dreams of groups journeying to Montgomery, collecting their rightful part of lynching history, and displaying it prominently back in their towns and cities. If people from a particular locale choose not to claim their piece, it will sit in stark relief on that Montgomery hilltop, a conspicuous token of unowned sin.

Courtesy EJI

Courtesy EJIThe Bible and Remembrance

For Americans in particular, monuments and memorials are sort of building blocks in a collective memory. Or as University of Pittsburgh historian Kirk Savage puts it, they attempt to “conserve what is worth remembering and discard the rest.”

For Christians, that is also a key function of the Bible—a collection of memories, divinely breathed to be passed down through traditions and communities. So many of the stories, especially in the Old Testament, are not cut-and-dried morality tales or inspirational anecdotes. They are portraits of people who were wrestling with loving God and loving their neighbors, and they are full of both cautionary notes and urgings to be more faithful and righteous. Remember God’s covenants; remember God’s commandments.

Failing to keep God’s commandments, even at the individual level, could inflict deep communal wounds. In Joshua 7, Achan’s decision to steal forbidden treasure from Jericho was not an individual affair for which he privately suffered the consequences—Achan’s family plus some 36 others lost their lives because of it.

In response to communal sins, the prophets modeled the importance of corporate confession. In Daniel 9, Daniel confessed to sins that happened in another location, in another generation—yet he considered it important to include himself in the confession of those corporate sins. “We and our kings, our princes and our ancestors are covered with shame, Lord, because we have sinned against you,” he prayed (v. 8). Similarly, both time and distance meant that Nehemiah was not personally present for the sins of idolatry and oppression that he confessed, but he knew that, for the sake of his people, there needed to be public acknowledgement of those sins.

The idea that corporate sin transcends time and generation is not limited to the Old Testament. “This generation will be held responsible for the blood of all the prophets that has been shed since the beginning of the world,” Jesus told the Pharisees (Luke 11:50–51). “Yes, I tell you, this generation will be held responsible for it all.” And few listening to Peter preach about “Jesus, whom you crucified” (Acts 2) had been present at Golgotha. Indeed, the “you” included “Parthians, Medes, and Elamites; residents of Mesopotamia, Judea and Cappadocia, Pontus and Asia, Phrygia and Pamphylia, Egypt and the parts of Libya near Cyrene; visitors from Rome [and] Cretans and Arabs.”

Nehemiah was never personally present for the sins of idolatry and oppression that he confessed. And yet he knew for the sake of his people, public acknowledgement of sin was required.

Leroy Barber was with me on the visit to EJI. The prominent black minister and writer often speaks about racial issues in the church. For him, the soil collection project and the proposed memorial were honoring, healing, and intensely personal. “My mother was born just south of Montgomery in a little place called Monroeville,” Barber told me. “So when I was there, looking at the maps of all the lynchings, I counted around seven or eight in the tiny town where my mom was born. And it was surreal. There was a deep sadness over the realities that my family lived through.”

For people like Barber, creating memorials and monuments in places like Montgomery is not just about corporate confession and repentance, although he believes those are important. He finds a strong biblical precedent for the importance of telling history well. “In Deuteronomy it says, ‘tell these stories, teach them to your children,’ so your children don’t forget, so your children know where they come from. This is a Christian position,” he said. “Bryan’s work is vital, in that it will free up a lot of people of color to tell their stories, to recreate the narrative for their children and grandchildren.”

Barber’s word reminded me of when I visited the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, DC, many years ago and was struck by Deuteronomy 4:9, displayed in large lettering in the Hall of Remembrance: “Only guard yourself and guard your soul carefully, lest you forget the things your eyes saw, and lest these things depart your heart all the days of your life, and you shall make them known to your children, and your children’s children.”

I had never thought about the importance of these verses, so integral to the people of God maintaining their faith and traditions, an admonition in the biblical context to remember God’s covenants as well as the dire consequences of breaking those covenants. It has become a common thread in any country or community that has experienced racial or ethnic violence. Remember, remember—so you do not forget and commit the same atrocities again.

As Stevenson often points out, our country is “littered with the iconography of the Confederacy,” which is both a partial retelling of history and also creates no space for repentance. “If we don’t confess our sins, we can’t be forgiven, and we just don’t do that very well in America.”

Facing the Sins of our Past

EJI has gathered the sort of celebrity endorsements required of a national initiative, including a partnership with Google to publish its research. But Stevenson, whose speaking engagements have included New York City’s Redeemer Presbyterian Church and the Willow Creek Association’s Global Leadership Summit, is especially eager to introduce EJI to a broader Christian audience.

To say that Christianity has a complicated history with racial injustice in the United States—including slavery, lynchings, and anti–civil rights politics—is an understatement. While we rightly celebrate Christian abolitionists like William Wilberforce in England, slavery in the South was upheld not only by individual Christian slaveholders and plantation owners but also by churches and denominations and theologians.

‘I am not interested in punishing America with this history,’ Stevenson told me. ‘I want to liberate us.’

Christians were often at the forefront of anti-slavery movements in 19th-century America, but the majority of Christians were not. Churches in the South vigorously defended the practice of slavery. In 1864, for example, the General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church in the Confederate States of America declared that “the long continued agitations of our adversaries have wrought within us a deeper conviction of the divine appointment of domestic servitude… . We hesitate not to affirm that it is the peculiar mission of the Southern Church to conserve the institution of slavery, and to make it a blessing both to master and slave.”

Only in recent decades have denominations begun to make more public efforts to confront their racially fraught pasts. The Southern Baptist Convention, founded in 1845 in large part over disagreements with northern Baptists over slavery, issued a sweeping declaration in 1995, apologizing for its complicity in systemic racism. For its part, the Presbyterian Church in America (PCA) confessed in 2002 for the role its forefathers played in upholding slavery. And in 2016 the PCA passed another overture, repenting of racism within the church during the civil rights era.

Yet it is hard to know how far such high-level confessional gestures have trickled down to individual churches and worshipers. As Americans, we are naturally gifted at elevating success but far more conflicted about selecting which tragedies to memorialize. It took only ten years to erect a memorial to the victims of September 11, Stevenson is fond of saying, and yet to this day there is no national monument to slavery.

Courtesy EJI

Courtesy EJIReligion intermingled with violence is nothing new, and you can find Bible-believing Christians on both sides of racial conflicts in many countries with a large Christian presence. Stevenson often points to this in interviews, noting how in Berlin, “you can barely go a hundred feet without seeing a monument that’s been placed at the home of a Jewish family that was abducted,” or how actual human skulls are on display in Rwanda’s genocide museum. But in America, he says, “We don’t talk about lynching. Worse, we’ve created the counter-narrative that says we have nothing about which we should be ashamed. Our past is romantic and glorious.”

Scripture teaches that repentance is not meant for harm but as a tool for turning from sin and walking a different path. In repenting, we acknowledge the fractures that sin has created both in our souls and in our social systems, and we commit to doing the work of repair. “I am not interested in punishing America with this history,” Stevenson told me. “I want to liberate us. I want us to find the path that gets us to redemption. And we can’t get there if we are unwilling to give voice to the truth of our past.”

In few places is that unwillingness on display as prominently as in Montgomery, where there are 59 markers commemorating and celebrating the Confederacy but, until 2013, there were none commemorating the domestic slave trade (EJI has now erected three such markers, noting Montgomery’s role as one of the busiest slave ports in the US). “I think we are a nation that has never truly sought truth and reconciliation,” Stevenson said. “And that we are not going to be free, really free, until we pursue that.”

Finding Common Ground

There are echoes of bygone Christian reform movements in Stevenson’s lynching memorial campaign.

University of Texas at Austin sociologist Michael Young has written extensively about how competing factions of believers—one emphasizing corporate sin, the other focusing on individual sin—came together in the early 19th century to launch temperance and anti-slavery movements. On one side, what were considered mainline orthodox Christian institutions of the time emphasized the idea of a covenantal society. They recognized the threat that national sins posed for America and, as a solution, called for strengthening the moral authority of the church. In contrast, upstart Christians of the era, such as Methodists, Baptists, and other smaller denominations, tended to view sin more as an individual matter.

In the 1830s, however, these two factions of Christianity found common ground in certain social causes, chief among them combatting alcohol abuse and slavery, which were seen as forces that warped both private and corporate morality. Based in part on a new, combined emphasis on both national sin and personal and public confession, these Christians launched some of the first social movements in the United States. Many churches publicly renounced slavery, due especially to public protests by middle-class Christian women eager to be involved in righting social wrongs. By 1838 there were 1,348 affiliated anti-slavery societies on record, pointing to a desire to address the moral sins of the time while other institutions remained silent.

“White abolitionists in the North, when they spread so quickly on the heels of the revivals of the Second Great Awakening, made this connection between their own personal [sins] and national problems,” Young said in an interview. “The joining of that intensive inward dimension and the extensive social dimension was the dynamism of the movement.”

Take, for example, the concluding statement of an anti-slavery resolution passed by the First Church of West Bloomfield, New York, in 1837: “And in this we pledge ourselves as individuals and as a church.” Sentiments like these, common among abolitionists, obligated both institutions and worshipers to confess as a way to end national sins and spare their own souls from the fallout.

That is the key similarity Young sees between confessional movements of old and what Stevenson hopes to accomplish through EJI and the lynching memorial: an element of personal transformation that goes deeper than the moral outrage of so many modern protests. “The crucial idea at the heart of ‘confessional protest’ is that it doesn’t have the same self-righteous component to it,” Young said. “The person bearing witness is sort of implicating herself as part of the problem.”

The Other Side of Repentance

Steve Jurvetson / Flickr

Steve Jurvetson / FlickrSean Lucas knows a few things about public confession. He worked for years to help the entire PCA do it.

The Reformed Theological Seminary professor was a coauthor of the 2015 resolution repenting for Presbyterians’ complicity in abuses during the civil rights era. The measure failed at that year’s general assembly, but a revised version passed in 2016.

“It shouldn’t have been a foreign or crazy idea, particularly for Reformed people,” Lucas said. Presbyterians have deep roots in the ideas of covenantal community and even that all believers in a given moment are bound together with other believers who are engaging in sin.

Lucas knows that public remembrance and confession for past sins, as Stevenson advocates, is not salvific. But “while it’s not necessary to be saved, evidence that you are in fact saved is a recognition of your sins but also the ways the sins of the generations continue to impact you and your community around you.”

Stevenson was struck by the power of repentance when he started working with men on death row. He remembers, as a young lawyer, seeing his clients and the people he represented as potential apostles who, like the apostle Paul, could be forgiven of much and could become models of what it means to be redeemed.

“We [as Christians] have an insight on what is on the other side of repentance, what is on the other side of acknowledgement of wrongdoing—which is repair,” Stevenson said. “And if we give voice to that, maybe we can encourage our nation to do better at recovering and acknowledging and responding to this history of bigotry and discrimination that has burdened us for so long.”

Creating New Memorials

Monuments and memorials are, by their nature, interpretive. They are almost always put up after the fact, and they tell a deeper narrative, not just about the histories they are intended to commemorate but about the values a society wants to preserve. So current debate about re-evaluating our memorials make sense, considering their power to shape and expand our understanding of history, injustices and all.

The heart of ‘confessional protest’ is that it doesn't have the same self-righteous component to it. The person bearing witness is sort of implicating herself as part of the problem.

That is at least the intent, for example, of church leaders who have fought to preserve a controversial anti-Semitic sculpture at a historic church in Germany. Instead of removing the sculpture, they added a plaque invoking repentance for the horrors of the Holocaust, lest we ever forget.

What does it mean to engage in these issues, as a Christian, when so many of us hold a skewed view of history formed, at least in part, by monuments that either dominate or are conspicuously absent from our public spaces?

For some of us it may well mean the need for a pilgrimage to Montgomery to reckon with our piece of the burden of history. For me, it meant finding myself in Coos Bay, Oregon, with my husband and two children, holding a large wooden cross, trying to honor the name and memory of a man I had never met.

There was no way of knowing if our makeshift memorial would mean anything in the long run. Would students walk by Tucker’s cross and Google his name? Would a teacher seize on it as an opportunity for a history lesson? Would it spark complaints, as the cross on the nearby Vietnam War memorial did recently from freedom-from-religion groups, a reminder that the struggle to mold memory is itself molded, for better or worse, by constantly shifting social mores? Or would a custodian simply find it and throw it in a dumpster, without a soul realizing the impact of the ground they were walking over?

I will never know. All I know is that my husband and I had made a pilgrimage to honor the name of a man who was the victim of racial violence, in my own state, less than a day’s drive from my home. We had been changed in the journey, and by the small and seemingly insignificant action of placing our own memorial. We could never unlearn what we found; we could never erase the horror of our past. We tried, in our own small way, to confront it. Because acknowledgement—along with repentance and lament—is something that we were raised with as Christians. We are trying to honor our histories by telling them in their entirety, and we are trying to teach them to our children, lest we all forget.

D. L. Mayfield is a frequent CT contributor and author of Assimilate or Go Home. Her most recent CT cover story was “Why I Gave Up Alcohol” (June 2014). She lives in Portland, Oregon. Additional reporting by Andy Olsen.

Have something to say about this topic? Let us know here .