Say “Florence Nightingale,” and instantly the word nurse pairs with it. Probably she was the most extraordinary nurse in history. Kings, queens, and princes all consulted her, as did the president of the United States, who wanted her advice about military hospitals during the Civil War.

It was Florence Nightingale who revolutionized hospital methods in England—and indeed throughout the world. During the Crimean War, she served in the first field hospital ever run and tended by women. She established schools for training nurses, and she introduced procedures that have been benefiting people ever since.

Still, this is an incomplete portrait. For years Florence acted as behind-the-scenes British secretary of war, managing to considerably better conditions for men in the armed services by setting up a system of health administration that was without precedent.

Suffering, wherever it existed, challenged her. She even set up a system for extending nursing care to the poor and the criminal underworld in the slums of English cities.

One reason Florence managed to accomplish so much was because any occupation but working for improved health standards seemed to her a waste of time. And Florence had remarkable stamina. When she was young, she sometimes worked twenty-two out of twenty-four hours.

Then, too, she was gifted with a peculiar genius: She could assimilate information in prodigious quantities, retain it, marshal her facts, and use them effectively. A relative wrote that when Flo was exhausted, the sight of a column of figures was “perfectly reviving to her.” Altogether she wrote eight lengthy reports and seventeen books on medical and nursing subjects.

Early Family Life

Florence was born in 1820 while her English parents, Fanny and William, were vacationing in Florence, Italy. She was named for her birthplace, although at that time Florence was not listed among feminine names, as it has been since Miss Nightingale gave it fame. She had an older sister, Parthenope (always called Parthe), who was also named for her birthplace.

Florence’s beautiful and intelligent mother and her wealthy, dilettante father were not very compatible, nor were the two little girls. Parthe, though she all but adored her sister, at the same time was envious and selfishly possessive of her.

It was impossible to find a tutor with the intellectual prowess demanded by Mr. Nightingale. So he assumed the responsibility himself, teaching the children Latin, Greek, German, Italian, French, English grammar, philosophy, and history. A governess was trusted to teach them only music and drawing.

When Parthe was eighteen and Flo sixteen, study was somewhat curtailed. The girls were presented at court and introduced to society. Their life then included many parties and much travel on the Continent.

Flo was tall, willowy, graceful, and pretty. Two young men promptly fell in love with her and proposed marriage. She liked them both, but she wasn’t ready to marry either.

Divine Mission

Then a strange thing happened. Though she did not think herself deeply religious and never thought she became so, on February 7, 1837, when she was scarcely 17 years old, she felt that God spoke to her, calling her to future “service.” From that time on her life was changed.

At first the call disturbed her. Not knowing the nature of the “service,” she feared making herself unworthy of whatever it was by leading the frivolous life that her mother and her social set demanded of her. Now she was given to periods of preoccupation, or to what she called “dreams” of how to fulfill her mission. Meanwhile she spent all her spare time visiting the cottages on her family estate and bringing neighboring poor people food and medicine.

When a family friend died in childbirth, Flo begged her parents to let her stay at the country home year round and take care of the baby instead of making her go to London for the winter social season. They vetoed the idea, believing she should mingle in society, eventually choose a husband, and bear children of the family bloodline. Too, Parthe had hysterics at the thought of the “ungrateful and unfeeling Flo” wanting to be separated from her.

In London one of Flo’s suitors again pressed her for an answer to his marriage proposal. She liked him, but she could not bring herself to say yes, especially when she did not know what “service” lay ahead.

Visiting her family home at the time were Dr. Howe and his wife, Julia Ward Howe (author of the “Battle Hymn of the Republic”). Florence asked Dr. Howe, “Do you think it unsuitable and unbecoming for a young Englishwoman to devote herself to works of charity in hospitals and elsewhere as Catholic sisters do? Do you think it would be a dreadful thing?”

He answered that it would be unusual and “whatever is unusual in England is thought unsuitable.” Nonetheless he advised her, “Act on your inspiration.”

If Florence was to consider nursing her “service”—and she was beginning to believe it must be—then she needed training. She proposed going to an infirmary run by a family friend.

Her parents were shocked, horrified, angry! She was a gentlewoman! Their objections were understandable. In that era English hospitals were places of degradation and filth. The malodorous “hospital smell” was literally nauseating to many, and nurses usually drank heavily to dull their senses. Florence herself admitted that the head nurse of a London hospital told her that “in the course of her long experience she had never known a nurse who was not drunken, and there was immoral conduct in the very wards.”

Years of Preparation

But at least Florence could study on her own. From a friend in Parliament, Sidney Herbert, she procured government reports on national health conditions. Then she got up at predawn every morning and pored over them by the light of an oil lamp, filling notebook after notebook with facts and figures, which she indexed and tabulated.

She planned to acquire practical experience by going to the unquestionably moral Institution of Lutheran Deaconesses in Kaiserwerth, Germany. Although her father called the move “theatrical,” and although Parthe again had hysterics, her parents reluctantly allowed her to go. After the Kaiserwerth stint the old pattern reappeared: Her parents wanted her to lead a “normal” life and were baffled and annoyed when she turned down another eligible suitor and seemed indifferent to marriage.

Then Florence met and confided in Cardinal Manning. He understood her aims, and she wondered if Catholicism could be her gateway to “service.” She proposed becoming a Catholic, but the cardinal demurred because she rejected certain Catholic tenets.

However he arranged for her to enter a Paris hospital staffed by nuns who obviously didn’t resort to drink. She would wear the postulant habit but live apart from the nuns. Shortly after she arrived, ironically, she came down with measles and had to leave.

Back in England, the Institution for Care of Sick Gentlewomen in Distressed Circumstances needed a superintendent. Florence’s study of health, hospital problems, and management recommended her. While she held this job, cholera broke out and nurses, fearing the disease, refused to serve, so Florence acted as a nurse herself and earned universal respect.

Opposition and Adulation

Then the Crimean War erupted. English military hospitals were a disgrace; in them a wounded man had almost no chance of recovery. When a reporter wrote that the French took far better care of their wounded, English consciences were stung into action.

Sidney Herbert, now secretary of war, not only authorized the purchase of hospital equipment, but also created a new of official position to which he appointed the bestqualified person he knew, Florence Nightingale. She became “Superintendent of the Female Nursing Establishment of the English General Hospitals in Turkey.” She was to go to Crimea with plenary authority, taking nurses of her choice.

Previously no woman had ever entered a military hospital. But because of Miss Nightingale’s reputation (she was called Miss Nightingale by the public), the order was applauded.

Now to implement it! First, how was she to find good nurses? Through Cardinal Manning a great concession was made: ten Catholic sisters were allowed to go to Turkey under Miss Nightingale’s leadership, subject to her orders. Eight Anglican sisters joined too, and Florence painstakingly gathered other women.

On arrival they found moldy food, scarce water, filth, overcrowding, no sanitary arrangements, no bedsheets, no operating tables, no medical supplies. The forty nurses were allotted a kitchen and five rat-and-vermin infested bedrooms; this meant crowding many nurses into each room.

Miss Nightingale had authority to requisition supplies, so she quickly asked for towels and soap and insisted that clothes be washed and floors scrubbed. That’s when she ran into trouble; some officers and doctors grumbled about her power. The superior of the Catholic sisters, although she had agreed to accept Miss Nightingale’s leadership, questioned why anyone but herself should direct the sisters, and she constantly made trouble. The Anglican nuns felt that Florence favored the Catholics.

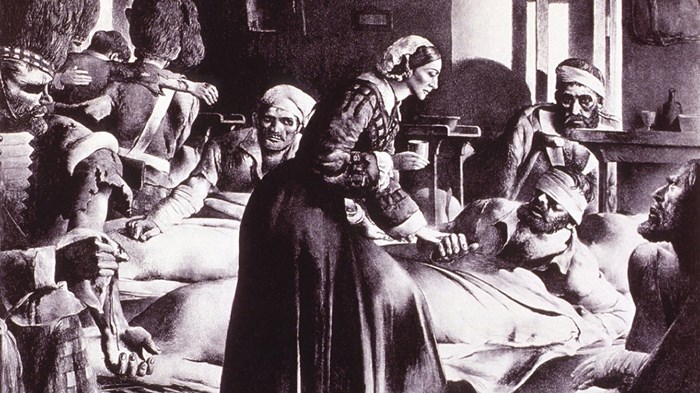

Only the patients—the wounded men—fully approved of her. They all but adored the “Lady of the Lamp,” as they called her when she visited the wards at the end of the day. They spoke of “kissing her very shadow” as she passed.

The Cost of Caring

Despite difficulties, Miss Nightingale went on working. She dressed wounds, administered or supervised medical treatments, instructed nurses, and made rounds of the wards. Then, before she dropped exhausted into bed near midnight, she spent an hour or two writing reports for the government at home.

She also suggested legislation to help the men. For example, the old law mandated that hospitalized men, since they were no longer in danger of being shot, have their pay cut. But their wounds often handicapped them for life, so Miss Nightingale opposed the pay cuts and wrote directly to Queen Victoria to explain why. The men’s pay was restored, just one instance among many where she suggested or wrote legislation that her friend Sidney Herbert introduced in Parliament.

When the war ended, she was the sole hero to emerge. As one biographer said, “She had the country at her feet.” The queen presented Florence with a diamond brooch. The inscription on the reverse side read, “To Miss Florence Nightingale as a mark of esteem and gratitude for her devotion toward the queen’s brave soldiers from Victoria R. 1855.”

Fighter for Reform

In Crimea, Florence had collapsed once or twice from overwork, and she returned home gaunt, pale, and suffering from several ailments. But she had no intention of resting. Military reforms were urgently needed. The mortality rate (73 percent in six months from diseases alone) was outrageous and resulted not from battlefield casualties but from the execrable state of the British army’s health administration.

Her aims were furthered when the queen summoned her to palace visits. Amazingly, the queen even made informal visits to her home. The women became friends, and Florence convinced Victoria of the value of her reforms. Although royalty could not act directly, the queen summoned the secretary of state to the palace along with Florence, so that she had an opportunity to present her ideas to him and to try to persuade him to act. Florence kept at him until he at least appointed a commission to study the matter.

The secretary of state then asked her for a detailed report. Night and day, she worked on the report; it ran 1,000 pages. Then she collapsed. She was seriously ill, but she had won her point. The government acted.

A friend, Sir John McNeill, wrote her, “To you, more than to any other man or woman alive, will henceforth be due the welfare and efficiency of the British army. I thank God that I have lived to see your success.”

Adviser, Writer, Educator

When her health improved, people came to her for advice, among them the queen of Holland and the crown prince of Prussia. Between visitors, she wrote books. Notes on Hospitals ran into three editions and was widely translated into other languages. After its publication, the king of Portugal asked her to design a hospital in Lisbon, and the government of India consulted her. Her next book, Notes on Nursing, sold thousands of copies in factories, villages, and schools and was translated into French, German, and Italian.

Writing mostly at night and working by day, she opened a nurses’ training school, using money given to a Nightingale Fund by the grateful British troops. If she had not done so before, surely now she changed forever the image of a nurse from that of a “drunken hussy” to that of an efficient attendant of the ill.

Despite illness, she pushed for reorganization of the War Office. One of her friends said that she was virtually secretary of state in the War Office for the next five years.

Her next big task came when a prominent Liverpool philanthropist approached her, begging nursing care for slum dwellers and workhouse inmates. She arranged to supply the care. Moreover, she called for legislation that would provide separate facilities for the children, the insane, and the victims of communicable diseases, who had previously lived cheek by jowl in the same workhouses.

No letup followed. Next came the Franco-Prussian War, during which Florence worked with the National Society for Aid to the Sick and Wounded, later called the British Red Cross Aid Society. When the war ended, Jean Henri Dunant said, “Though I’m known as the founder of the Red Cross … it is to an Englishwoman that all the honor is due. What inspired me … was the work of Florence Nightingale.”

For an interval, however, she did slacken her public work to devote herself to nursing first her dying father, then her dying mother, and then her dying sister, Parthe, with whom she was closer than in bygone years.

Florence lived on into old age, always supervising work at the Nightingale Fund School and always and everywhere being treated with a respect akin to awe. In 1907 Edward VII bestowed on her the Order of Merit; it was the first time it had ever been given to a woman. She continued to write until her sight failed, her memory dulled, and she became a little vague. On August 13, 1910, she fell asleep around noon and did not awaken.

Mary Lewis Coakley is the author of twelve books and resides in Wyncote, Pennsylvania.

Copyright © 1990 by the author or Christianity Today/Christian History magazine.

Click here for reprint information on Christian History.

Support Our Work

Subscribe to CT for less than $4.25/month