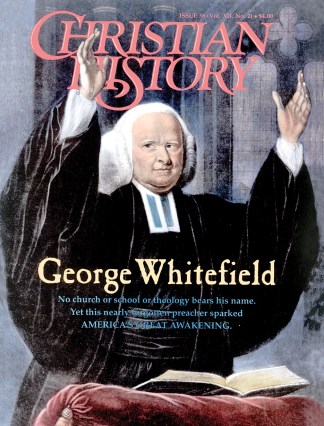

"I would give a hundred guineas, if I could say 'Oh' like Mr. Whitefield." — Actor David Garrick

Largely forgotten today, George Whitefield was probably the most famous religious figure of the eighteenth century. Newspapers called him the "marvel of the age." Whitefield was a preacher capable of commanding thousands on two continents through the sheer power of his oratory. In his lifetime, he preached at least 18,000 times to perhaps 10 million hearers.

Timeline |

|

|

1675 |

Spener's Pia Desideria advances Pietism |

|

1682 |

William Penn founds Pennsylvania |

|

1707 |

Isaac Watts publishes Hymns and Spiritual Songs |

|

1714 |

George Whitefield born |

|

1770 |

George Whitefield dies |

|

1780 |

Robert Raikes begins his Sunday school |

Born thespian

As a boy in Gloucester, England, he read plays insatiably and often skipped school to practice for his schoolboy performances. Later in life, he repudiated the theater, but the methods he imbibed as a young man emerged in his preaching.

He put himself through Pembroke College, Oxford, by waiting on the wealthier students. While there, he fell in with a group of pious "methodists"—who called themselves "the Holy Club"—led by the Wesley brothers, John and Charles. Under their influence, he experienced a "new birth" and decided to become a missionary to the new Georgia colony on the other side of the Atlantic Ocean.

When the voyage was delayed, Whitefield was ordained a deacon in the Anglican church and began preaching around London. He was surprised to discover that wherever he spoke, crowds materialized and hung on every word.

These were no ordinary sermons. He portrayed the lives of biblical characters with a realism no one had seen before. He cried, he danced, he screamed. Among the enthralled was David Garrick, then the most famous actor in Britain. "I would give a hundred guineas," he said, "if I could say 'Oh' like Mr. Whitefield."

Once, when preaching on eternity, he suddenly stopped his message, looked around, and exclaimed, "Hark! Methinks I hear [the saints] chanting their everlasting hallelujahs, and spending an eternal day in echoing forth triumphant songs of joy. And do you not long, my brethren, to join this heavenly choir?"

Whitefield eventually made it to Georgia but stayed for only three months. When he returned to London, he found many churches closed to his unconventional methods. He then experimented with outdoor, extemporaneous preaching, where no document or wooden pulpit stood between him and his audience.

Spellbound crowds

In 1739, Whitefield set out for a preaching tour of the American colonies. Whitefield selected Philadelphia—the most cosmopolitan city in the New World—as his first American stop. But even the largest churches could not hold the 8,000 who came to see him, so he took them outdoors. Every stop along Whitefield's trip was marked by record audiences, often exceeding the population of the towns in which he preached. Whitefield was often surprised at how crowds "so scattered abroad, can be gathered at so short a warning."

The crowds were also aggressive in spirit. As one account tells it, crowds "elbowed, shoved, and trampled over themselves to hear of 'divine things' from the famed Whitefield."

Once Whitefield started speaking, however, the frenzied mobs were spellbound. "Even in London," Whitefield remarked, "I never observed so profound a silence."

Though mentored by the Wesleys, Whitefield set his own theological course: he was a convinced Calvinist. His main theme was the necessity of the "new birth," by which he meant a conversion experience. He never pleaded with people to convert, but only announced, and dramatized, his message.

Jonathan Edwards's wife, Sarah, remarked, "He makes less of the doctrines than our American preachers generally do and aims more at affecting the heart. He is a born orator. A prejudiced person, I know, might say that this is all theatrical artifice and display, but not so will anyone think who has seen and known him."

Whitefield also made the slave community a part of his revivals, though he was far from an abolitionist. Nonetheless, he increasingly sought out audiences of slaves and wrote on their behalf. The response was so great that some historians date it as the genesis of African-American Christianity.

Everywhere Whitefield preached, he collected support for an orphanage he had founded in Georgia during his brief stay there in 1738, though the orphanage left him deep in debt for most of his life.

The spiritual revival he ignited, the Great Awakening, became one of the most formative events in American history. His last sermon on this tour was given at Boston Commons before 23,000 people, likely the largest gathering in American history to that point.

"Scenes of uncontrollable distress"

Whitefield next set his sights on Scotland, to which he would make 14 visits in his life. His most dramatic visit was his second, when he visited the small town of Cambuslang, which was already undergoing a revival. His evening service attracted thousands and continued until 2:00 in the morning. "There were scenes of uncontrollable distress, like a field of battle. All night in the fields, might be heard the voice of prayer and praise." Whitefield concluded, "It far outdid all that I ever saw in America."

On Saturday, Whitefield, in concert with area pastors, preached to an estimated 20,000 people in services that stretched well into the night. The following morning, more than 1,700 communicants streamed alongside long Communion tables set up in tents. Everywhere in the town, he recalled, "you might have heard persons praying to and praising God."

Cultural hero

With every trip across the Atlantic, he became more popular. Indeed, much of the early controversy that surrounded Whitefield's revivals disappeared (critics complained of the excess enthusiasm of both preacher and crowds), and former foes warmed to a mellowed Whitefield.

Before his tours of the colonies were complete, virtually every man, woman, and child had heard the "Grand Itinerant" at least once. So pervasive was Whitefield's impact in America that he can justly be styled America's first cultural hero. Indeed, before Whitefield, it is doubtful any name, other than royalty, was known equally from Boston to Charleston.

Whitefield's lifelong successes in the pulpit were not matched in his private family life. Like many itinerants of his day, Whitefield was suspicious of marriage and feared a wife would become a rival to the pulpit. When he finally married an older widow, Elizabeth James, the union never seemed to flower into a deeply intimate, sharing relationship.

In 1770, the 55-year-old continued his preaching tour in the colonies as if he were still a young itinerant, insisting, "I would rather wear out than rust out." He ignored the danger signs, in particular asthmatic "colds" that brought "great difficulty" in breathing. His last sermon took place in the fields, atop a large barrel.

"He was speaking of the inefficiency of works to merit salvation," one listener recounted for the press, "and suddenly cried out in a tone of thunder, 'Works! works! A man gets to heaven by works! I would as soon think of climbing to the moon on a rope of sand.'"

The following morning he died.

Corresponding Issue