Clergymen hovering along the sidelines; athletes proselytizing like revival preachers; and “Jocks for Jesus” steadily colonizing locker rooms nationwide.

This was the brave new sports world that journalist Frank Deford described in a 1976 three-part series for Sports Illustrated on religion and sports. “It is almost as if a new denomination had been created,” Deford posited. “Sportianity.”

Deford was writing at a unique historical moment. Newsweek had proclaimed 1976 “The Year of the Evangelical,” as presidential candidate Jimmy Carter identified as a “born again” Christian. Evangelicals, it seemed, were everywhere—even in the games that people played and loved.

More than simply documenting this trend, though, Deford channeled his inner-most H. L. Mencken and produced a whimsical and astute lament of the burgeoning Sportian movement. “They endorse Jesus, much as they would a new sneaker or a graphite-shafted driver,” he quipped.

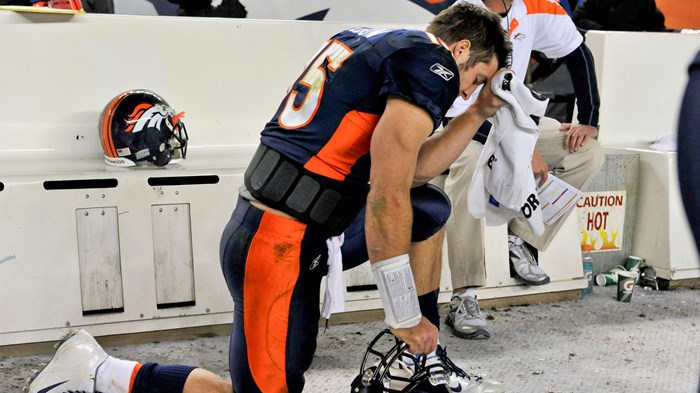

In the 40 years since Deford’s profile, Sportians have become increasingly ubiquitous. Indeed, the mere fact of their presence is no longer noteworthy. It takes a more conspicuous act or angle to get attention: think of A. C. Green’s celibacy, Orel Hershiser’s singing of the doxology, or Tim Tebow’s sideline gesticulations.

But while the “Christian athlete” phenomenon may have intensified in recent decades, a look back at our past reveals a lengthy history of evangelical Protestant involvement in sports. Long before Deford deployed his now-infamous neologism, Christian athletes made playing and praying part of their athletic identity.

Here, then, is a list of ten noteworthy “proto-Sportians" in American history.

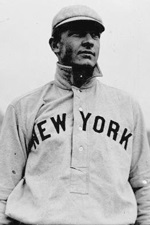

Billy Sunday (1862–1935): Baseball

Billy Sunday was a gifted professional baseball player with the Chicago White Stockings when, in the summer of 1886 after leaving a bar, he and his friends came upon a street preacher. Inspired, Sunday soon dried up and converted, leaving his life of vice behind him. He also became a passionate advocate for the faith. At YMCAs across the nation, Sunday drew enormous crowds who clamored to hear the famous baseball player recall his faith journey.

In 1891, Sunday quit baseball for a position with the YMCA as an evangelist, teacher, and emissary. Athletic allusions saturated his sermons. He directed crowds to lead a “ninth-inning rally” for Christ, to fling a “fastball at the devil,” and he called Jesus “the greatest scraper that ever lived.” Additionally, Sunday’s revival performances were demonstrations of physicality and aggressiveness taken from the playing fields, as he slid down the center-aisle and threw chairs across the stage.

Sunday was no sophisticated theologian or thinker. But he was a charismatic revivalist who made sports a central piece of his performances.

Amos Alonzo Stagg (1862–1965): Football

Before he became the “Grand Old Man” of football, Amos Alonzo Stagg pioneered in promoting Christianity from the baseball diamond. A star pitcher for Yale in the 1880s, Stagg used his athletic fame to write baseball articles for the McClure newspaper syndicate. He also toured the northeast on behalf of the YMCA, lecturing on how to be a Christian athlete.

Stagg’s deep commitment to amateur athletics led him to resist overtures from professional baseball teams. Instead, he cast his lot with another sport at which he excelled: football. After enrolling at the YMCA Training School in Springfield, Massachusetts in 1890, Stagg founded and captained a football team. Coincidentally, one of his teammates was James Naismith, a fellow former-seminarian who would later invent the game of basketball.

Stagg’s squad was inexperienced. But they were ambitious and innovative, finishing the season with a close loss to Yale. The ragtag collection of players also bore an uncanny physical resemblance to their captain—short, stocky, full of grit and determination, and outwardly Christian. “Let us pray for God’s blessing on our game,” Stagg would announce before each game, as his team earned the nickname, “Stagg’s Stubby Christians.”

This was an era when a movement known as “muscular Christianity” was taking hold in American Protestant culture. The legacy of puritanical suspicion about sports being a frivolous distraction was a thing of the past. In its place were ministers, theologians, and an entirely new creature—the professional coach—who argued that a well-played game was just as spiritually edifying as a prayer service. Stagg’s entire life was a monument to this movement.

Christy Mathewson (1880–1925): Baseball

In the early days of professional baseball, players had a reputation for all the things that 19th-century middle-class Protestants opposed: drunkenness, gambling, Sabbath-breaking, and sexual escapades. There was a reason that Amos Alonzo Stagg turned down offers to join the pro game in the 1880s and that it took a street preacher to clean up Billy Sunday. But Christy Mathewson, college-educated at the Baptist-affiliated Bucknell University, helped to make the professional game more palatable to the “respectable classes.”

Beginning his pro career in 1900, Mathewson’s pitching brilliance and his deft use of the burgeoning world of sports journalism enabled him to win widespread acclaim for his clean-living, church-going life. By the 1910s, Protestant pastors and magazine editors alike often turned to “The Christian Gentleman” to attract listeners and readers to their message. Stories of Mathewson’s moral uprightness abounded: In one tale, Mathewson slid into home on a bang-bang play. The umpire, unable to see the tag, turned to Mathewson. “I was out,” Mathewson admitted, before explaining to the flabbergasted catcher that he was duty-bound to tell the truth because “I am a church elder.” Mathewson’s saintly image was boosted, too, by his untimely death in 1925 at age 45. The day after his death, fans attending the World Series matchup between the Pittsburgh Pirates and Washington Senators honored Mathewson by joining together for a chorus of “Nearer My God to Thee.” And in 1951, Mathewson’s Christian faith was given a more permanent symbol: He was one of four athletes memorialized in granite in the just-completed Sports Bay at Cathedral Church of Saint John the Divine in New York.

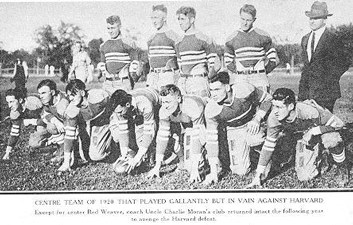

The “Praying Colonels” of Centre College (1921): Football

In our present day, the South arguably has the most overtly evangelical football fields in the nation. And it all started with a program that few remember. While the North had men like Stagg and Mathewson as exemplary Christian athletes, the South had Centre College.

In 1921, this backwater school from Kentucky traveled to New England and defeated the mighty Harvard Crimson. “Centre Saves the South!” proclaimed the Atlanta Constitution. It was the first time that a southern team defeated the Ivy powerhouse. And as news of the previously unknown team spread, sports fans puzzled over their unique nickname, the “Praying Colonels.” The story goes that prior to a game against Kentucky—a team that had defeated Centre the previous year by a score of 66–0—someone suggested that they collectively pray for divine assistance. Silence filled the room until one player burst forth and proclaimed, “Let me lead that damned prayer!” And with that, the legend was born. When asked about what they prayed for, the team’s star quarterback Bo McMillian remarked, “We didn’t pray to win, we simply prayed that we could use our best ability. We prayed that we would play clean; we prayed that we would give our best efforts and that we would be worthy of the heritage of the school that we were representing.”

Joe Louis (1914–1981): Boxing

When Joe Louis left home to embark on what would become a legendary boxing career, his mother reportedly gave him a Bible—a Bible that he would claim to read every night. As pictures of the fighter reading his Bible circulated through the media during the 1930s, white America was comforted by one important fact: Joe Louis was not Jack Johnson.

In 1908, Johnson won the heavyweight title after pummeling the white champion Tommy Burns in a match staged in Australia. “The fight! There was no fight,” novelist Jack London mourned. Johnson was brash, outspoken, and gleefully willing to trample upon the racial norms of the Jim Crow America. After Johnson lost the title in 1915, the white boxing world effectively ousted African Americans from the sport—until Joe Louis.

The humble, soft-spoken, Bible-toting boxer who loved his mother was precisely the pugilist that white America could rally behind. And rally they did when Louis fought Germany’s Max Schmeling in 1936 and again in ’38. American sportswriters depicted it as a proxy battle with Nazi Germany, with a win for Louis translating to a win “for America.” Some writers even hoped that Louis’s mythic stature would become a solution to domestic conflicts. Journalist Ed Van Every called the boxer the “Black Moses,” sent to knock out racial intolerance.

To be sure, African Americans had no shortage of admiration for Louis. Langston Hughes was among the chorus of voices singing his praises. But Louis’s carefully manicured image, which conspicuously featured his Christianity, afforded the boxer widespread hero status in a time when virulent anti-black racism was the norm.

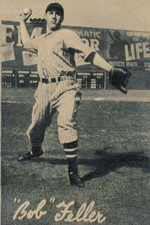

Bob Feller (1918–2010): Baseball

Born and raised in the small Iowa town of Van Meter (population 300), Bob Feller took the nation by storm when he debuted for the Cleveland Indians as a 17-year-old halfway through the 1936 season. With a blazing fastball, the “Heater from Van Meter” struck out 15 batters in his first major league start. After his abbreviated rookie season, Feller returned to Iowa for his senior year of high school before getting right back to his pitching dominance.

Feller’s exploits from the pitching mound are well known today. Less remembered is his very public religious life. During his first six seasons, four decades before sports chaplains become a recognizable feature on pro sports teams, Feller had a personal pastor to meet his spiritual needs. Newspapers frequently reported on the friendship between the pitching phenom and the Rev. Charles Fix, a Methodist minister who traveled to Feller’s games in between his Sunday sermon duties. Realizing they had a star, Methodist leaders sought to capitalize on Feller’s fame: In 1938, Feller attended the youth section of the Methodist Conference, where he and Rev. Fix urged youngsters to faithfully attend church.

Gil Dodds (1918–1977): Track and Field

In the 1940s, Gil Dodds was arguably America’s finest middle-distance runner. Hailing from Kansas and rural Nebraska, Dodds was the son of a Brethren minister, an upbringing that left an indelible mark on his character. During his track career, Dodds became known as “The Flying Parson,” and he habitually signed autographs by including Phil. 4:13 (“I can do all this through him who gives me strength”).

On Memorial Day in 1945, 65,000 people came to the Chicagoland Youth for Christ Rally at Soldier Field to watch him run an exhibition mile. There, Dodd told the audience, “Running is only a hobby. My mission is teaching the gospel of Jesus Christ.” In 1947, he raced and evangelized at a Billy Graham Crusade in Charlotte, North Carolina. Graham himself was a sports fan, with a special affinity for baseball. So he welcomed this addition to the event. But Graham’s associates didn’t know what to make of Dodds—until they witnessed the hordes of young people attending the Crusade to see the runner. Sports stars would soon become a fixture at Graham’s Crusades and similar revival events.

As for Dodds, when his running career ended, he worked with a new organization called Youth for Christ. He also coached track and cross-country at Wheaton College, where hundreds of runners will be competing in the Gil Dodds Cross-Country Invitational this fall.

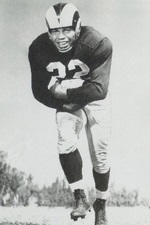

Dan Towler (1928–2001): Football

In Crazylegs, the 1953 biopic about Los Angeles Rams star receiver Elroy "Crazylegs" Hirsch, a remarkable scene occurs: Before a must-win 1951 game against the San Francisco 49ers, the Rams team huddles together for final instructions from head coach Joe Stydahar. After Stydahar is finished, fullback “Deacon” Dan Towler (playing himself) pipes up. “Coach, this is the game we’ve gotta win. Would you mind if I said a prayer in the huddle?” Stydahar obliges, and there, on screen in the year before Brown v. Board, a black man leads an interracial football team in prayer.

Although the scene was somewhat embellished, it did have a ring of truth. As a rookie in 1950, Towler famously led the team in prayer before a preseason game. That, combined with his interest in studying the Bible and talking about religion, earned him the nickname “Deacon.” Over six seasons from 1950 to 1955, Towler relished his religious reputation, all while spearheading the Rams’ “Bull Elephant” rushing attack and earning four All-Pro selections. After the 1955 season Towler retired from the game in order to become a Methodist minister. But he continued his association with sports by working closely with the Fellowship of Christian Athletes over the next couple decades.

Patsy Neal and the Wayland Baptist Flying Queens: Basketball

Decades before the Connecticut dynasty in women’s basketball, a tiny Baptist college in the Texas Panhandle dominated the sport. Playing in the Amateur Athletic Union (AAU), the Wayland Baptist Flying Queens reeled off 131 consecutive wins over a four-and-a-half year stretch from 1953 and 1958 and won six titles between 1953 and 1961. In that era, most physical educators and college administrators frowned on intercollegiate athletic competition for women. Instead, they preferred club basketball or “play days,” during which women from area colleges would gather together for a day of recreation. Afterwards, they often adjourned for tea and cookies (really). With no officially sanctioned college basketball championship for women, a few colleges turned to the AAU circuit—a league made up mostly of company-sponsored semi-professional teams—in order to give their women’s basketball teams a chance to compete.

Wayland Baptist began playing women’s AAU basketball in the late 1940s. Their innovative president envisioned using the team to spread the gospel and boost school enrollment. But it wasn’t until 1953, when the school began offering full scholarships for women’s basketball players, that the Flying Queens really took off. Because few other schools offered these kinds of scholarships, Wayland immediately become a premiere destination for the top high school players. It helped, too, that most of the top high school players at the time hailed from small towns and farms in the South or Midwest: In the 1920s and 1930s, most public high schools in northern states had shut down competitive basketball for girls.

Patsy Neal, a farm girl from Georgia, joined the Flying Queens before the 1956 season. Although she did not kick-start the Wayland dynasty—star post player Lometa Odom deserves more credit for that—she did earn AAU All-American honors in 1959 and 1960. And, while some Flying Queens did not necessarily promote themselves as “Christian” athletes, Neal was one of the few women athletes to establish connections with the Fellowship of Christian Athletes in the pre-Title IX 1960s.

Wilma Rudolph (1940–1994): Track and Field

Wilma Rudolph’s path to becoming the “Fastest Woman in the World” was far from predictable. The 20th of 22 children, Rudolph lived most of her first 12 years wearing a brace on her left leg, the result of childhood illnesses. When she finally began walking unencumbered, doctors, family, and Rudolph herself were collectively astonished. They were even more astonished four years later when she won a bronze medal in the 1956 Olympics as the member of the 4x100 relay team. Then, in 1960, she took home three individual Olympic golds in sprinting events.

While the thrill of victory elevated Rudolph’s spirits for a time, she was deeply concerned about her place in life. “I tried to ask God why was I here? What was my purpose? Surely, it wasn’t just to win three gold medals. There has to be more to this life than that.” Soon, the Olympic star would draw upon her Baptist upbringing to fill this void. She did mission work with the likes of Billy Graham, traveling to West Africa and Japan as a member of Baptist Christian Athletes. But she was also known to put her faith into action, even when it made people uncomfortable. When Rudolph’s Tennessee hometown announced a parade in her honor after the 1960 Olympics, the sprinter protested that she would not attend if it was segregated. Officials conceded, and the parade was the first desegregated event in the city’s history.

After her track and field career ended, Rudolph became an educator, coach, and speaker, all the while further cementing her reputation as a pioneer for women’s rights and civil rights. Led by her Christian conviction, Rudolph made sports part of her pursuit of justice and empowerment. She once told the Chicago Tribune “The triumph can’t be had without the struggle,” whether in sports or in life.

Paul Putz is a Ph.D. candidate in history at Baylor University and is writing a dissertation on the Fellowship of Christian Athletes. Arthur Remillard is Associate Professor of Religious Studies at Saint Francis University and is currently writing a religious history of sports in America.

Support Our Work

Subscribe to CT for less than $4.25/month