More than 1 million Facebook users have watched Louis Farrakhan proclaim that the living Jesus will save him from death, and that he will pay a price for his former teachings as the leader of the Nation of Islam.

Yet what seemed to some Christian outsiders like a move toward biblical repentance was, according to expert observers, actually a common tactic in Farrakhan’s messaging: using Christian language to apply to the African American movement’s own theology.

“It sounds like, because he used Jesus, that he’s talking about the biblical Jesus,” said Atlanta preacher Damon Richardson, who was born and raised in the Nation of Islam but found Jesus—the Christian one—at 16.

“I’ve got pastors and friends who are sharing the video, saying, ‘Hallelujah, praise God for this conversion,’ and they are not doing the research.”

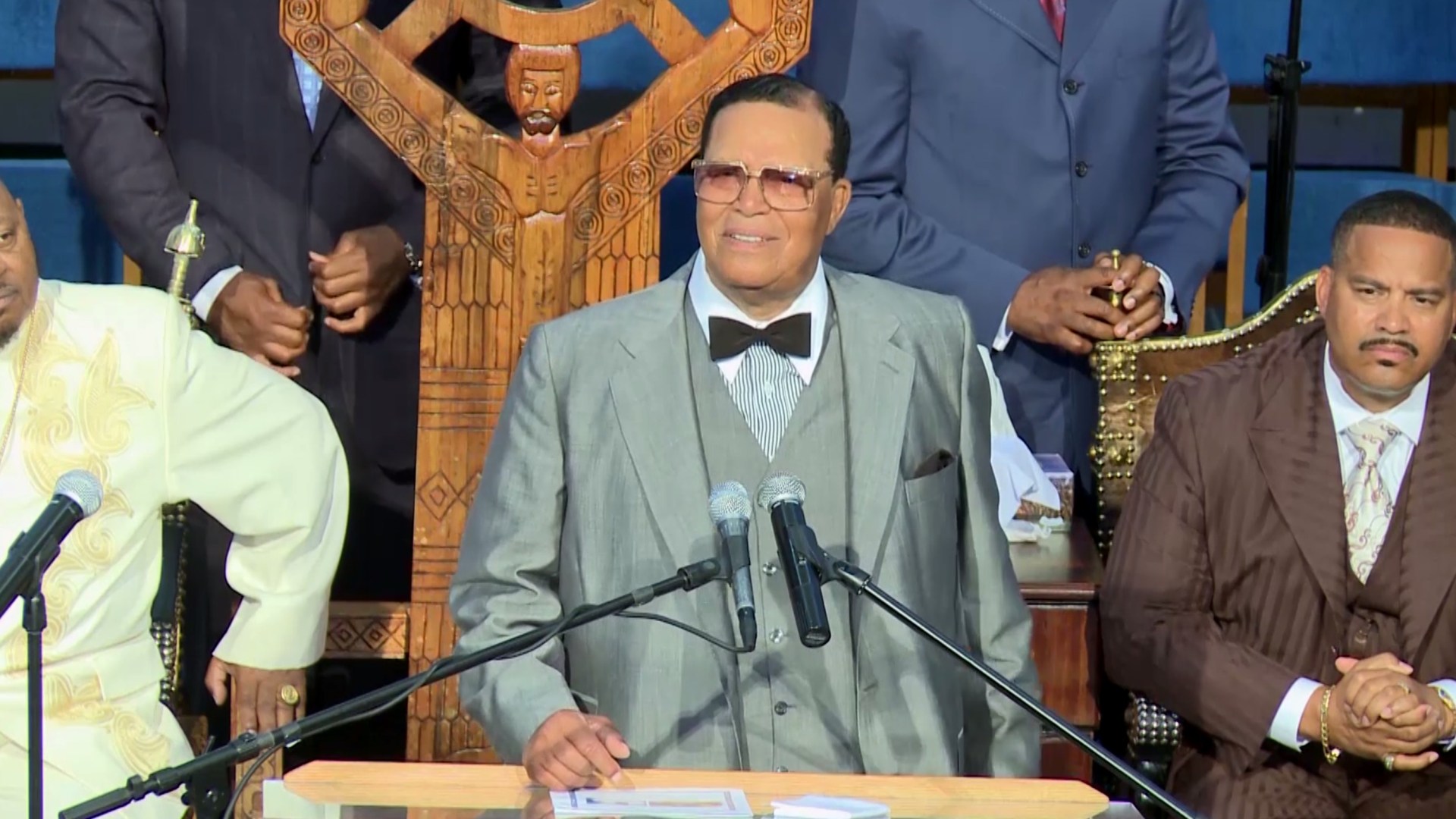

Farrakhan gave his remarks earlier this month at a Washington church where he has guest-preached for decades, and posted a clip on Facebook which has been viewed by more than 1.3 million people. The 84-year-old minister said:

I thank God for guiding me for 40 years absent my teacher. So my next journey will have to answer the question. I'm gonna say, I know that my redeemer liveth. I know, I'm not guessing, that my Jesus is alive. I know that my redeemer liveth and because he lives I know that I, too, will pass through the portal of death yet death will not afflict me.

So I say to the devil, I know I gotta pay a price for what I’ve been teaching all these years. You can have the money, you can have the clothes, you can have the suit, you can have the house but, me, you can’t have.

His language rings familiar for churchgoers. But Richardson, an urban apologist speaking on Facebook in response, said the clip offers a lesson in the importance of using sound hermeneutics—including understanding how a message was originally intended and received.

Farrakhan restructured the Nation of Islam in the 1970s following its longtime leader and his mentor Elijah Mohammad, who died in 1975. He ultimately declared Mohammad as a new savior sent from Allah.

“When he says, ‘I know that my redeemer lives,’ this is a reference to the fact that he believes Elijah Mohammad, while physically absent, is physically alive,” Richardson said. (This is a shift in the Nation of Islam’s theology, since founder Wallace Fard Muhammad was originally seen as the savior and was even honored with a holiday called “Saviours’ Day.”)

“When [Farrakhan] says, ‘I know I’m going to have to pay a price for what I’ve been teaching all these years,’ this is not a denouncing of the teaching. This is an affirmation that he believes what he has been teaching is right,” Richardson said. “The price is death, imprisonment, or some sort of persecution for exposing the identity of the devil, who the Nation of Islam teaches is the white man.”

Even after Christians’ due diligence on Farrakhan’s latest remarks reveal that he has not moved away from his own teachings, they can continue to pray for him and all in the Nation of Islam, said apologist and church planter D. A. Horton.

The Nation of Islam began as a black nationalist and Islamic movement to “teach the downtrodden and defenseless black people a thorough knowledge of God and of themselves.” In a 2000 interview with CT, theologian Carl Ellis described the Nation of Islam among several groups with “a theology based on the historical core cultural issues of African Americans—dignity, identity, significance, empowerment—along with various doctrines that claim God is black and the white man is the devil.”

Though its numbers aren’t as high as during the 1960s and 1970s, the group under Farrakhan continues to have a presence in major cities and a closer relationship with some black churches who ascribe to black liberation theology, according to Richardson.

“His relationship with the black church has grown over the year because of his tendency to use Scripture and Christian language,” Richardson said in an interview with CT. “It’s the skin of the truth, stuffed with a lie.”

Farrakhan has made hundreds of references to Jesus over the course of his ministry and incorporated God’s son in his teaching, including attributing the light shining from the east (Matt. 24:27) to Elijah Mohammad.

Many Nation of Islam speakers also follow the “language, symbols, and rhythm of black church culture” in their style, according to Washington pastor Thabiti Anyabwile.

“It is definitely a deceptive means that the Nation of Islam will use to lure unsuspecting Christians,” said pastor Ernest Leo Grant II, who has written about the need for a new approach to defending the Christian faith in the inner city.

Grant, who leads Epiphany Fellowship of Camden, New Jersey, listed the Nation of Islam, along with Moorish Science Temple of America and Black Hebrew Israelites, as the top sects offering urban African Americans an alternative to Christianity.

Farrakhan in particular “is known for appropriating and transposing Christian terms to make them more appealing,” Grant said. “Evangelicals should be concerned about the Nation of Islam in general because they are causing some to fall away.”

Christian rapper Sho Baraka spoke on The Calling podcast about his own upbringing in the Nation of Islam, and the need for theological training to address similar cults and sects that appeal to African Americans.

The growing field of urban apologetics—with an eye toward poverty, justice, diversity, violence, and a city’s cultural distinctives—has worked to train leaders to serve that mission.

“Sadly, in the black community, we have conceded these issues either to liberation theology or to black nationalist groups like the Nation of Islam,” Christopher Brooks, a pastor in Detroit where the Nation of Islam began, told CT in 2013. “There needs to be a strong evangelical voice in our urban areas that says, ‘Here is what the gospel has to say about justice.’”