“But why should I get a new Bible, when the words of my Bible speak so sweetly to my heart?” an elderly lady said, as it was suggested to her that perhaps she would like to obtain one of the more modern translations. On the other hand, another person, who had recently purchased a modern-language translation of the New Testament, declared, “Why, in the few months since I’ve had this new version, I’ve read the Bible more than for ten years. Now, it makes sense.”

These two responses are typical of the differences which have always existed between the old and the new—the continuing conflict between loyalty to the past and concern for the present and the future. It would be quite wrong to imagine that these diverse attitudes concerning different translations of the Bible came into being only after the recent publication of the Revised Standard Version. The accompanying publicity, both pro and con, no doubt threw the spotlight upon certain underlying tensions between “traditionalists” and “contemporaries” (if we may apply such names), but conflicts over new and old translations of the Scriptures in English preceded even the King James Version. In fact, the strong adherents to the Geneva Version, published approximately fifty years before the King James, first opposed the Bishops Bible, published some ten years after their Geneva Version, but when the King James Version appeared, they spared no words of bitter criticism in denouncing the scholars whom they contended had distorted the Word of God.

500 English “Translations”

Between the time of the King James Version, published first in 1611, and the present time, those opposing new English translations and revisions have had plenty of opportunity to denounce the work of persons attempting to put the Scriptures in a more intelligible form, for since 1611 a total of more than 500 translations of the Scriptures have been published in English. These have consisted of twenty-seven full Bibles, over seventy-five New Testaments, more than 150 publications of less than a New Testament, but not printed as parts of commentaries, and the rest, often consisting of major portions of the Bible, printed as new translations to accompany expositions of the meaning of the Scriptures. Even during the last fifty years there has been an amazing increase in revisions of the Scriptures into English, so that scarcely a year passes without some new revision of the Bible or New Testament coming off the press.

This almost unbelievable interest among English-speaking people in new translations of the Scriptures (their interest is manifest by the fact that most of these translations have proven to be profitable publishing ventures), is, however, not an isolated phenomenon. There is scarcely a major language in the world in which Scripture revision is not now going on. These include not only such major European languages as German, French, Norwegian, Russian, Polish, Lithuanian, Hungarian, Greek, Spanish, and Dutch, but almost all the important so-called “missionary languages” of the younger churches throughout the world, e.g. Chinese, Tagalog, Cebuano, Indonesian, Thai, Nepali, Tibetan, Bengali, Hindi, Marathi, Zulu, Swahili, Chiluba, Hausa, Bulu, and Cuzco Quechua. In fact, there are major revisions now going on in more than 90 languages in the world, and further translating in another 175 languages, with other translators at work to produce the Scriptures in at least 200 languages which have never had anything of the Word of God.

In the light of so many revisions being made throughout the world, one is inevitably led to ask two kinds of questions: (1) Do all of these revisions tend to meet with the same types of opposition from those who insist, whether rightly or wrongly, that the old is better? and (2) What are the reasons for so many revisions, especially at this time? Is this the result of liberal theology, especially in the mission field? Or is this possibly a genuine “return to the Bible”?

In reply to those who may question the widespread nature of opposition to revision, one can only say that in greater or lesser degree it has always been present. Even the King James Revisers had to deal with the same kinds of complaints, as their Introduction to the Reader (unfortunately omitted from practically all modern editions) so ably testifies, for their work had already encountered strong opposition and they knew it would meet with ungrateful bitterness. Accordingly, they wrote in the Preface:

Zeale to promote the common good whether it be by devising any thing our selves, or revising that which hath bene laboured by others, deserueth certainly much respect and esteeme, but yet findeth but cold intertainment in the world.…

For he that medleth with mens Religion in any part medleth with their custome … and though they finde no content in that which they have, yet they cannot abide to heare of altering …

Many mens mouths have bene open a good while (and yet are not stopped) with speeches about the Translation so long in hand, or rather perusals of Translations made before: and aske what may be the reason, what the necessitie of the employment: Hath the Church bene deceived, say they, all this while?… Was their Translation good before? Why doe they now mend it? Was it not good? Why then was it obtruded to the people?…

It is quite understandable that those who have been led to a personal acceptance of Jesus Christ through a message communicated to them in a particular version should feel that such a translation was not only fully adequate for themselves but equally valid for everyone else. Moreover, those who by long habit or because of vested interests become attached to a particular form of the Scriptures are very unlikely to give up the old without a struggle. It should not be surprising, therefore, that revisions of the Bible have in general been condemned from the time of Wycliffe and Tyndale right down to the present.

Reasons For Revision

Certainly there must be some important reasons for the fact that at present there are more revisions and new translations in process throughout the world than at any other time in the history of the Christian Church. One cannot, however, point to any one reason as being either the exclusive or the principal factor in any one revision. Persons who have felt led to undertake such tasks have usually been induced to do so by a number of reasons, including (1) the existence of more accurate textual evidence, (2) important new information as to the meanings of biblical terms, (3) significant improvements in the interpretation of passages, (4) the inevitable changes which occur constantly in any living language and (5) a re-emphasis upon the principle of intelligibility as the valid basis for legitimate translating.

Better Textual Evidence

In John 1:18 the King James Version and all traditional translations read, “the only begotten Son, which is in the bosom of the Father.” However, some of the important manuscripts discovered during the past century have what was regarded by many as a strange reading, for instead of “only begotten Son” these manuscripts read “only begotten God”—such an unmistakable declaration of the deity of our Lord that certain persons insisted that this must have been a change introduced by some overzealous scribe. But in the recently published Bodmer II papyrus, which dates from the second century A.D., the reading of “only begotten God” is unmistakably confirmed. It would be impossible, of course, to declare unequivocally that “only begotten God” was the reading of the autograph of John’s Gospel, but it is most important that this significant variant be incorporated into modern translations, whether in the text itself or in the margin, for a translation which fails to provide its readers with this important new light is robbing them of some of the most important evidence from the best manuscripts.

There are some instances in which textual differences seem only very slight, but may be highly meaningful. For example, in the traditional rendering of John 7:52 there has always been a problem for exegetes, for it would appear as though the Greek meant, “No prophet ever comes out of Galilee,” which, of course, was not true of Jewish history. To help to remedy this situation Owen suggested some years ago that the text should be amended at this point and that a single article should be added, so that the passage would read, “The prophet (meaning, of course, the Messiah) will not come out of Galilee.” Imagine the keen interest of scholars who in going through the Bodmer II papyrus discovered that in this earliest extant text of John the article, suggested by Owen, is present. Undoubtedly, this passage in John 7:52, instead of being a rather oblique reference to the Messiah, is a direct one, and completely in keeping with the obvious intent of the Gospel account.

In addition to these two minor details, coming from the most recently available textual evidence, there are of course numerous other instances in which better biblical manuscripts have immeasurably improved the sense of passages. For example, in 1 John 5:18 we are no longer constrained to believe that “he that is begotten of God keepeth himself” (speaking of the effort of the redeemed to keep themselves from sin). Because of the absence of a single letter in the better Greek manuscripts, this passage should be translated, “He who was begotten by God keeps him” (indicating clearly that it is Christ Himself who keeps those who trust in Him). Rather than being fearful of the results of textual research, we who place our confidence in the inspiration of the writers of the Scriptures, rather than in the inerrancy of scribes, can be not only intellectually thankful for such greater accuracy but spiritually blessed by the more meaningful message.

It might seem anachronistic to speak of new meanings for words of the Bible, when obviously these words only had meanings in a society of at least 2,000 years ago. Nevertheless, during the last century an immense amount of study and research has gone into the careful examination and evaluation of masses of information coming from the Bible lands. The most important sources of our information are to be found in the tens of thousands of papyri fragments and scrolls, including everything from grocery lists to funeral orations. These scraps of paper have contained many examples of the words also found in the Bible, and thus have provided clues to meanings which were unknown to early translators of the Scriptures into English. For example, the Greek adverb ataktos (and the related derived verb) translated in the King James Version as “disorderly” in 2 Thessalonians 3:6, 7, and 11 really refers to people who “live in idleness.” The meaning of idleness fits the context immeasurably better than “walking disorderly,” for it is in this passage that Paul insists that if one does not work he should not eat. Furthermore, Paul calls attention to his own practice of working for a living with his own hands, as an example of one who was “not idle” (verse 7).

Another term which in the papyri suggests the possibility of a significant difference in meaning is the Greek word hypostasis, rendered as “substance” in most translations of Hebrews 11:1. This same word, however, has been found to be the term for a “title deed” to property. This passage, therefore, may have a meaning which is much more concrete than what has often been assumed. Accordingly, faith may simply be “the title deed of the things hoped for,” for it is faith which makes future hope a present possession.

The careful study of words has resulted in removing several instances of apparent contradiction from the Scriptures. In Galations 6:5 the King James text says, “every man shall bear his own burden,” but in the same chapter, verse 2, the text reads, “bear ye one another’s burdens.” Such renderings are understandably confusing to many people, but a close examination of the two different Greek terms employed in these verses soon clears up the difficulty. The word used in the second verse refers to excessively heavy burdens, and the word in verse 5 means one’s legitimate load. Contemporary Biblical studies have clarified the meanings of hundreds of such passages of Scripture, and it is thus little wonder that people throughout the world are demanding that they have revisions which will reflect certain of these more accurate renderings of the Word of God.

More Accurate Interpretations

All improvements in text and the meanings of individual words inevitably add up to more accurate interpretations. However, there is a class of changes which is somewhat distinct from these other two, for though the text remains the same and the meanings of the words are not significantly altered by lexical research, nevertheless, modern translations have profited by important exegetical suggestions. In John 1:9, for example, the traditional rendering of “the true Light, which lighteth every man that cometh into the world” implies a kind of automatic enlightenment of each person on being born. However, this is not really the import of this passage. The theme of this Gospel is the coming of the light into the world, not the coming of men. Accordingly, most modern translations have followed an alternative rendering, “the true Light, which enlightens every man, was coming into the world.”

Similarly, in Romans 1:17 and Galatians 3:11 the traditional interpretation has been “the just shall live by faith.” This is, of course, quite a possible interpretation of the Greek expression, which is itself a literal rendering of the Hebrew original in Habakkuk. However, there is an equally valid rendering which is much more in keeping with the theme treated in Romans and Galatians, for in these two Epistles Paul was not dealing primarily with “living by faith” but with “being justified by faith.” Hence, the interpretation of “those who through faith are just shall live” should certainly be recognized, whether in the text or in the margin.

There are, of course, some persons who object to marginal notes in the Bible, for they think that these tend to detract from the authority of the Word, thus depriving the message of its full force. Interestingly enough, the translators of the King James Version were faced with this same accusation, and in an effort to forestall such criticisms they said in their introduction:

Some peradventure would have no variety of senses to be set in the margine, lest the authoritie of the Scriptures for deciding of controversies by that shew of uncertaintie, should somewhat be shaken. But we hold their judgment not to be so sound in this point … Therefore as Saint Augustine saith, that varietie of Translations is profitable for the finding out of the sense of the Scriptures: so diversitie of signification and sense in the margine, where the text is not so cleare, must needs doe good, yea, is necessary, as we are persuaded.

It is unfortunate for the average reader of the Scriptures that in so many editions of the King James Version the hundreds of marginal notes introduced by the translators have been omitted (except for certain reference editions which include them in the reference column), for their continued printing would have done much to correct false ideas and attitudes about biblical revelation.

This does not mean that editions of the Bible should be filled with the differences of scholarly viewpoints, but complete honesty and integrity dictate that those who are aware of such legitimate diversities in rendering should indicate to the reader when there are alternatives. Anything less than this is not only misleading, but a betrayal of our Protestant heritage, which looks to the Scriptures rather than to human tradition for its authority.

Changes In Living Languages

Another important reason for continued revisions is that no living language stands still. It is in a state of constant change in every aspect, whether in the pronunciation of words (as reflected often in spellings), in grammatical forms, syntactic arrangements of words, or the meanings of terms. People of the seventeenth century had no difficulty understanding “prevent” in the sense of “go ahead of” (1 Thess. 4:15) or “let” (2 Thess. 2:7 and Romans 1:13) with the meaning of “hinder” (compare the legal phrase “without let or hindrance”). They rightly preferred “Holy Ghost” to “Holy Spirit,” but during the intervening years since 1611 the words ghost and spirit have completely changed meanings, for now ghost is understood by us as an apparition, precisely what spirit meant in the time of King James. People of that day could reckon by cubits, rods, furlongs, and firkins, but we need some equivalent in feet, yards, miles, and gallons. For the sake of greater accuracy and intelligibility we must use different words, e.g. “morsel” instead of “sop” (John 13:30), “prune” instead of “purge” (John 15:2), “rooms’ instead of “mansions” (John 14:2), and “Counselor” instead of “Comforter” (John 14:16), to mention only a few.

Rather than “changing the meaning” of the King James Version, as some have claimed, such modern words serve more to “restore the meaning.” In many instances the fault is not with the traditional translations, but with the English language which has changed, but most people are relatively unaware of what has happened.

Re-Emphasis Upon Intelligibility

The importance of communication in our contemporary world has made it fully evident that if a translation does not communicate the meaning of the original it is not really a translation, but a string of words. Accordingly, an idiom such as “children of the bridechamber” (which can be grossly misinterpreted) has usually been changed in modern translations to “wedding guests,” or more specifically “friends of the bridegroom.” Similarly, the strange phrase “bowels of mercy” has been rendered more meaningfully as “tender compassion.” However, in order to make for greater intelligibility modern translations have not only modified the forms of idioms, but have often simplified the complex structure of difficult sentences.

In John 1:14 the phrase “full of grace and truth” obviously refers to the Word, earlier in the verse, but when it is placed at the end of the verse, even though after a parenthesis, its meaning may be readily confused. Accordingly, a rearrangement of order is not only fully legitimate but helps to convey the meaning of the original, which in Greek is quite clear because of the grammatical forms, but which in English can be entirely misleading if the words are left in their Greek order. It is often necessary that long, involved sentences be broken up into shorter, more intelligible ones. Compare, for example, the traditional translations of Ephesians 1:3–14 (which is usually one long sentence, even as it is in Greek) with modern translations, which may use as many as half a dozen sentences, with considerable improvement in sense.

One must not imagine, however, that this striving for greater intelligibility is purely a contemporary development. The King James translators were for their day real pioneers in this field, and as a result they suffered from their critics. On the one hand, they shunned the newfangled ultramodern terms of the time proposed by the Puritans, and on the other, they rejected a host of traditional words used by the Roman Catholics and the strict conservatives. Their ultimate purpose was intelligibility, and in stating their intent, these translators wrote, “But we desire that the Scripture may speak like itself, as in the language of Canaan, that it may be understood even of the very vulgar.” (By which, of course, they meant the common people.)

This basic principle employed by the King James revisers, namely, that the message in English should be as intelligible to the common man as the original was in its setting in “Canaan,” cannot be improved upon. This means, however, that if one is to follow the same principle one must not hesitate to revise the Scriptures or to use such revisions.

Today, even as in the seventeenth century, there are those whose basic suspicion of learning and scholarship has prompted them to decry revisions of the Scriptures, whether of the King James Version in that day or of various modern revisions in our own. Moreover, there has been in some circles the impression that revisions are generally the outgrowth of scholarly perversity in trying to upset people’s faith. Such charges have been made not only against various English revisions, but perhaps even somewhat more against revisions on the mission field. The truth of the matter is that most revisions are promoted primarily by a desire for evangelistic outreach, and this is especially true for the mission field. When a church is spiritually dead—content with its ritualistic practices and its liturgical forms—there is no life to encourage any revision. It is only when the church becomes aware of its need to communicate the Word of God with greater effectiveness that there is an urge to revise or to translate afresh.

Perhaps, however, the strangest contradiction in certain phases of contemporary Bible translation and revision is that some of those who most loudly proclaim their belief in literal inerrancy cling most tenaciously to traditional translations which in many instances are not based on the best manuscripts, and which at times contain inaccurate interpretations. Apparently, for fear that to give in an inch to modern scholarship will result in complete capitulation, those who affirm so strongly their acceptance of the truth as “God-breathed” frequently have resisted attempts to introduce any changes into the traditional forms. However, rather than being fearful of what might come from research in matters of text and interpretation and hence reluctant to participate in or promote such endeavors, conservatives should be in the forefront of any such undertakings. We have everything to gain and nothing to lose (except perhaps a few pet sermons) by the discovery of the truth as revealed to us in the earliest manuscripts and through the most reliable interpretations. Because the Bodmer II papyrus agrees with the best ancient manuscripts in not containing John 5:4 (the story of the angel disturbing the water in the Pool of Bethesda) and John 7:53 to 8:11 (the story of the woman taken in adultery), we should not be disturbed. Such facts should not prejudice anyone against textual studies, especially when the Bodmer II papyrus does contain such an important reading as “only begotten God.” However, our reactions to scholarship must not be dictated by whether or not present-day discoveries confirm or deny our own theological views. It is the “truth which shall make us free,” and it is this truth which alone can free us from our past errors (regardless of how precious they may have seemed) and reveal to us God’s Word and will. This new appreciation of truth, as expressed in the processes of revision and translation, is the only basis for a common rallying point for all those who love him who declared himself “the way, the truth, and the life.”

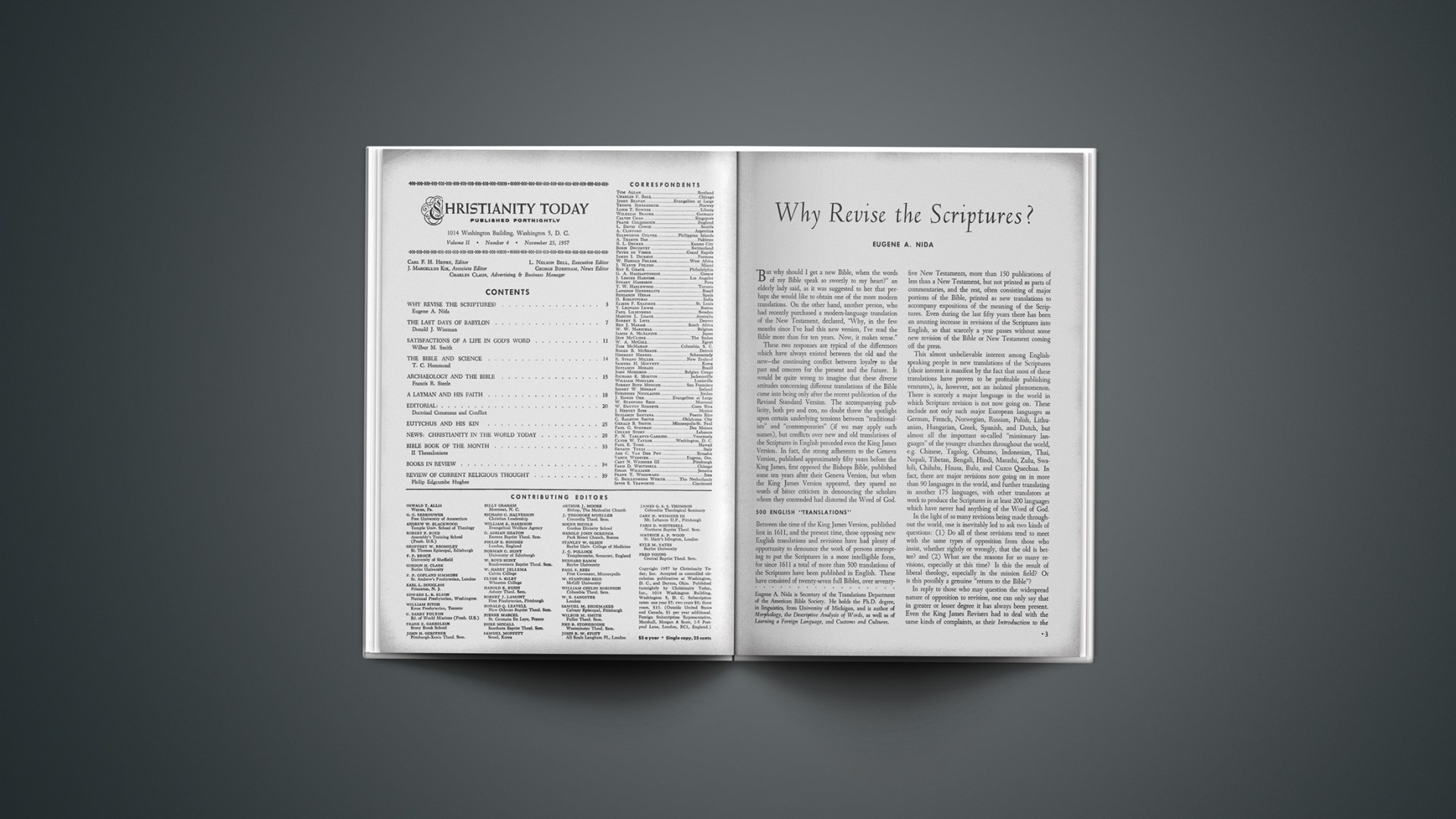

Eugene A. Nida is Secretary of the Translations Department of the American Bible Society. He holds the Ph.D. degree, in linguistics, from University of Michigan, and is author of Morphology, the Descriptive Analysis of Words, as well as of Learning a Foreign Language, and Customs and Cultures.