In the Book of Jonah (1:3) there is recorded his trip from Joppa to Tarshish, and we are told “he paid his fare thereof.” This is the first instance we have of a transportation fare being paid by a prophet of the Lord, and the inference is that he paid the regular rate.

Today many religious leaders and clergymen would like to see the airlines make the same concession to them as is made by the railroads. During 1953 Secretary of Commerce recommended that Congress pass the needed authority to make this possible. The Senate bill would have permitted free or reduced fares, but Congress in 1956 amended the Civil Aeronautics Act giving the airlines permission to grant reduced rate transportation to ministers of religion on a “space available” basis.

This permission to date has been accepted by five of the smaller companies who accord fares of one half their first-class fare. The larger companies, with a request pending for a general increase in fares, are not anxious to reduce their revenue and further feel that to accord same on a “space available” basis could incur bad reactions and also encourage a similar request from eleemosynary and government authorities.

In the year 457 B.C., during the reign of Artaxerxes, King of Persia, permission was given the scribe, Ezra, with a company of 1,700 to go from Babylon to Jerusalem to rebuild the temple, and the King (Ezra 7:24) certified “that touching any of the priests and Levites, singers, porters … or ministers of this house of God, it shall not be lawful to impose toll, tribute, or custom, upon them.”

Thus the first clergy passed over the highways of that day without paying toll or the modern fare.

In an old book of by-laws of an English turnpike company we find this: “Toll is not to be demanded or taken of any Rector, Vicar or Curate going to or returning from visiting any sick parishioner or his other parochial duties within his parish.”

This same rule was followed on early American toll roads; and in addition, lay persons going to and from their house of worship on Sundays were exempt.

A contract between the Colonial government of Georgia and an owner of a ferry in 1761 stated that ministers of the Gospel and students of divinity should cross free of toll.

A history of the Erie Railroad states that clergy were first carried free by this company under the following circumstances: Early in the spring of 1843 the Reverend Doctor Robert McCartee, pastor of the Presbyterian Church at Goshen, was a passenger of an Erie Railroad train operated by Conductor Ayers. On account of a very heavy rain, the track was in such bad condition that the train was delayed for hours. Some of the passengers drew up a set of resolutions denouncing the company in scathing terms. When these were presented to Dr. McCartee he said he would be glad to add his signature if the phraseology was changed slightly. He wrote the following:

“Whereas, the recent rain has fallen at a time ill-suited to our pleasure and convenience and without consultation with us: and

“Whereas, Jack Frost, who has been imprisoned in the ground several months, having become tired of his bondage, is trying to break loose, therefore be it

“Resolved, that we would be glad to have it otherwise.”

When Dr. McCartee arose and, in his best parliamentary voice, read his proposed amendment, there was a hearty laugh and nothing more was heard about censoring the management. Conductor Ayers was so delighted with this turn of affairs that thereafter he would never accept a fare from Dr. McCartee. Not being a selfish man, the doctor suggested a few weeks later that the courtesy be extended to all ministers. The company thought the idea a good one and for a time no minister paid to ride on the Erie Railroad.

An official of one of the early railroads said that when they gave a pass to a minister they expected to receive their reward in heaven, while a secretary reporting to the president the issue of 18 annual passes to bishops, and other clergy remarked, “The ministers are pretty good advertisers.”

It is apparent that the railroads used the ministers to gain public favor. Special sermons were requested on the “moral effect” of railroads.

A minister wrote to the Belfast & Moosehead Lake Railroad in 1871 that he proposed to hold semi-monthly services in Brooks and asked that a pass from Burnham be given him. After due consideration, the president of the road replied: “Your favor of yesterday asking for a free pass is at hand. This company is disposed to lend all possible aid toward the advancement of the Gospel. It recognizes specially the need of regenerating influences and a change of heart in the field of your proposed endeavors at Brooks, which has repudiated its subscription to this road. With the hope that your prayers and exhortations may be efficacious to that end, I enclose the pass requested.”

A stockholder of 1878 complained in a letter to Railway Age Magazine about according ministers half fares, to which a railroad official replied through the same columns, in part:

“The clergyman is a public servant to a greater extent even than members of our legislatures. His work especially tends to the improvement of public morals, and the more he moves about sowing the seeds of better social and spiritual life, the more will all commercial interests be advanced. We undertake to say that every step or stage of advancement toward the thorough permeation of the community with church influence and Christian sentiment, the more secure is railroad property and the more prosperous are railroad interests.”

The Iowa Railroad Commissioners in 1882 reported: “Sheriffs are given passes for somewhat the same reason that clergymen get them. The latter are encouraged to raise the standard of character throughout the State and the former to lay hands upon those whose standard of character is so low as to make treatment of a penal nature necessary. The railroads feel that the more the parson and the sheriff can be encouraged to travel the more safe life and property will be on their lines.”

During 1920 the question of permitting reduced clergy fares on the railroads in the state was raised by the railroad commission of the State of Pennsylvania with the result that the question was submitted to popular vote. The answer was their continued sale.

The Western railroads in 1921 increased clergy fares to two-thirds of the regular fare, at which time it was feared the action foretold ultimate abolition. Certain ministers said that such action would be disastrous to the clergy, since they would be denied the benefit of conventions, inspirational retreats, and the like, while others thought that any and all concession should be refused. One said, “From the time of the seminary we have accepted too much graft.”

During 1938 the Long Island Railroad appealed to the clergy along its lines requesting they use their influence with the children to discontinue mischievous and malicious practice such as throwing stones at trains, etc.

Latest development in the long and colorful history came recently when President Dwight Eisenhower signed a bill in which Congress authorized airlines to reduce the fare for clergymen—on a standby basis.

The bill means practically nothing, however. Major airlines have not requested such permission from the Civil Aeronautics Board, and the clergy have not applied much pressure for them to do so. Ministers using such a plan would chance missing flights with no vacancies or cancellations. Most ministers, with packed work-schedules, could not travel under such uncertainties.

Clergy fares or no clergy fares, however, ministers are among the busiest travelers around the world.

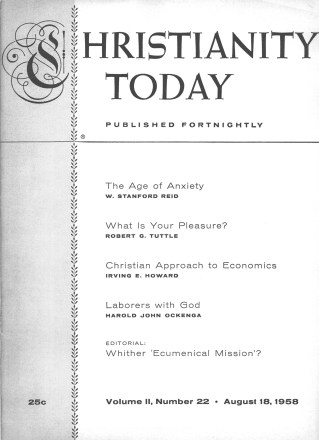

Clyde H. Freed is author of The Story of Railroad Passenger Fares and has written numerous articles for trade journals. He holds the Bachelor of Laws degree from Georgetown University. In 1956 he retired as ticket agent at Union Station, Washington, D. C., where he had been working since 1910. He is now engaged as an employee of Christianity Today.