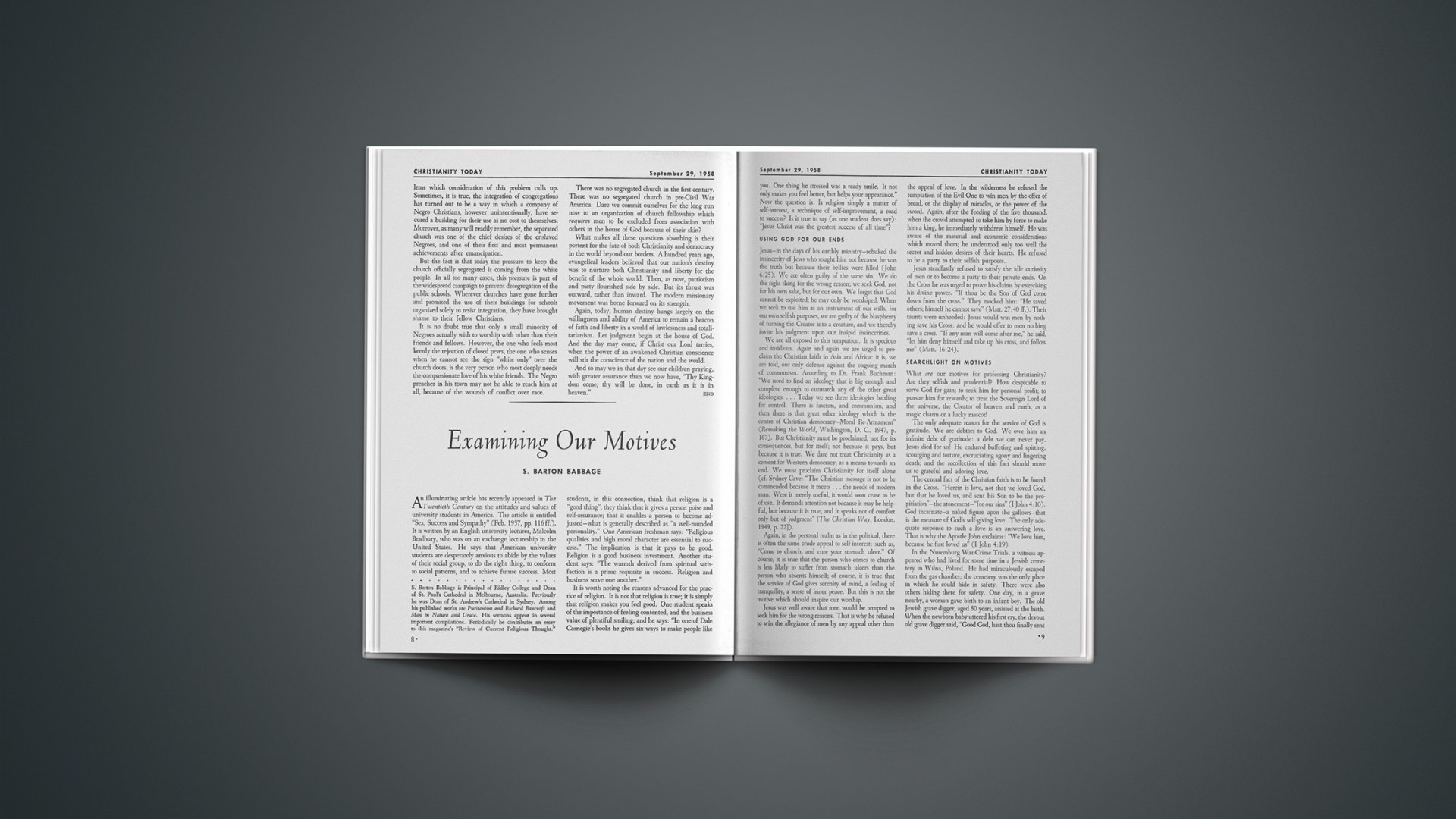

An illuminating article has recently appeared in The Twentieth Century on the attitudes and values of university students in America. The article is entitled “Sex, Success and Sympathy” (Feb. 1957, pp. 116ff.). It is written by an English university lecturer, Malcolm Bradbury, who was on an exchange lectureship in the United States. He says that American university students are desperately anxious to abide by the values of their social group, to do the right thing, to conform to social patterns, and to achieve future success. Most students, in this connection, think that religion is a “good thing”; they think that it gives a person poise and self-assurance; that it enables a person to become adjusted—what is generally described as “a well-rounded personality.” One American freshman says: “Religious qualities and high moral character are essential to success.” The implication is that it pays to be good. Religion is a good business investment. Another student says: “The warmth derived from spiritual satisfaction is a prime requisite in success. Religion and business serve one another.”

It is worth noting the reasons advanced for the practice of religion. It is not that religion is true; it is simply that religion makes you feel good. One student speaks of the importance of feeling contented, and the business value of plentiful smiling; and he says: “In one of Dale Carnegie’s books he gives six ways to make people like you. One thing he stressed was a ready smile. It not only makes you feel better, but helps your appearance.” Now the question is: Is religion simply a matter of self-interest, a technique of self-improvement, a road to success? Is it true to say (as one student does say): “Jesus Christ was the greatest success of all time”?

Using God For Our Ends

Jesus—in the days of his earthly ministry—rebuked the insincerity of Jews who sought him not because he was the truth but because their bellies were filled (John 6:25). We are often guilty of the same sin. We do the right thing for the wrong reason; we seek God, not for his own sake, but for our own. We forget that God cannot be exploited; he may only be worshiped. When we seek to use him as an instrument of our wills, for our own selfish purposes, we are guilty of the blasphemy of turning the Creator into a creature, and we thereby invite his judgment upon our insipid insincerities.

We are all exposed to this temptation. It is specious and insidious. Again and again we are urged to proclaim the Christian faith in Asia and Africa: it is, we are told, our only defense against the ongoing march of communism. According to Dr. Frank Buchman: “We need to find an ideology that is big enough and complete enough to outmarch any of the other great ideologies.… Today we see three ideologies battling for control. There is fascism, and communism, and then there is that great other ideology which is the centre of Christian democracy—Moral Re-Armament” (Remaking the World, Washington, D. C., 1947, p. 167). But Christianity must be proclaimed, not for its consequences, but for itself; not because it pays, but because it is true. We dare not treat Christianity as a cement for Western democracy; as a means towards an end. We must proclaim Christianity for itself alone (cf. Sydney Cave: “The Christian message is not to be commended because it meets … the needs of modern man. Were it merely useful, it would soon cease to be of use. It demands attention not because it may be helpful, but because it is true, and it speaks not of comfort only but of judgment” [The Christian Way, London, 1949, p. 22]).

Again, in the personal realm as in the political, there is often the same crude appeal to self-interest: such as, “Come to church, and cure your stomach ulcer.” Of course, it is true that the person who comes to church is less likely to suffer from stomach ulcers than the person who absents himself; of course, it is true that the service of God gives serenity of mind, a feeling of tranquility, a sense of inner peace. But this is not the motive which should inspire our worship.

Jesus was well aware that men would be tempted to seek him for the wrong reasons. That is why he refused to win the allegiance of men by any appeal other than the appeal of love. In the wilderness he refused the temptation of the Evil One to win men by the offer of bread, or the display of miracles, or the power of the sword. Again, after the feeding of the five thousand, when the crowd attempted to take him by force to make him a king, he immediately withdrew himself. He was aware of the material and economic considerations which moved them; he understood only too well the secret and hidden desires of their hearts. He refused to be a party to their selfish purposes.

Jesus steadfastly refused to satisfy the idle curiosity of men or to become a party to their private ends. On the Cross he was urged to prove his claims by exercising his divine power. “If thou be the Son of God come down from the cross.” They mocked him: “He saved others; himself he cannot save” (Matt. 27:40 ff.). Their taunts were unheeded: Jesus would win men by nothing save his Cross: and he would offer to men nothing save a cross. “If any man will come after me,” he said, “let him deny himself and take up his cross, and follow me” (Matt. 16:24).

Searchlight On Motives

What are our motives for professing Christianity? Are they selfish and prudential? How despicable to serve God for gain; to seek him for personal profit; to pursue him for rewards; to treat the Sovereign Lord of the universe, the Creator of heaven and earth, as a magic charm or a lucky mascot!

The only adequate reason for the service of God is gratitude. We are debtors to God. We owe him an infinite debt of gratitude: a debt we can never pay. Jesus died for us! He endured buffeting and spitting, scourging and torture, excruciating agony and lingering death; and the recollection of this fact should move us to grateful and adoring love.

The central fact of the Christian faith is to be found in the Cross. “Herein is love, not that we loved God, but that he loved us, and sent his Son to be the propitiation”—the atonement—“for our sins” (1 John 4:10). God incarnate—a naked figure upon the gallows—that is the measure of God’s self-giving love. The only adequate response to such a love is an answering love. That is why the Apostle John exclaims: “We love him, because he first loved us” (1 John 4:19).

In the Nuremburg War-Crime Trials, a witness appeared who had lived for some time in a Jewish cemetery in Wilna, Poland. He had miraculously escaped from the gas chamber; the cemetery was the only place in which he could hide in safety. There were also others hiding there for safety. One day, in a grave nearby, a woman gave birth to an infant boy. The old Jewish grave digger, aged 80 years, assisted at the birth. When the newborn baby uttered his first cry, the devout old grave digger said, “Good God, hast thou finally sent the Messiah to us? For who else than the Messiah himself can be born in a grave?” But after three days the witness said that he saw the baby sucking his mother’s tears because she had no milk for the child (quoted from Paul Tillich, The Shaking of the Foundations, London, 1949, p. 165).

It is a story of profound poignancy, of moving emotional power. And yet we forget that the Son of God—the Messiah himself—was born in an animal’s feeding trough, in the stench of an Eastern stable, and that he died in loneliness and dereliction on a cross, having drunk to the bitter dregs the cup of human tears. The prophet Isaiah states the truth in immortal words:

He was wounded for our transgressions, he was bruised for our iniquities; the chastisement of our peace was upon him.… He was oppressed, yet when he was afflicted he opened not his mouth; as a lamb that is led to the slaughter, and as a sheep that before its shearers is dumb, so he opened not his mouth. By oppression and judgment he was taken away … they made his grave with the wicked, and with the rich man in his death; although he had done no violence, neither was any deceit in his mouth (Isa. 53:5–9).

The remembrance of this fact should humble our pride and subdue our selfishness. It should move us to penitence. It was our sins which nailed him to the Cross; it was in our place that he bore the penalty. And it is the recollection of this fact—this fact above everything else—that should evoke our gratitude and win our love and inspire our service.

My God, I love Thee; not because

I hope for heaven thereby,

Nor yet because who love Thee not

Are lost eternally.

Thou, O my Jesus, Thou didst me

Upon the Cross embrace;

For me didst bear the nails, and spear,

And manifold disgrace.

And griefs and torments numberless,

And sweat and agony;

Yea, death itself; and all for me

Who was Thine enemy.

Then why, O Blessed Jesus Christ,

Should I not love Thee well?

Not for the sake of winning heaven,

Nor of escaping hell;

Not from the hope of gaining aught,

Not seeking a reward;

But as Thyself hast loved me,

O ever-loving Lord.

So would I love Thee, dearest Lord,

And in Thy praise will sing;

Solely because Thou art my God,

And my most loving King.

(Translated by Caswall from a 17th century Latin hymn.)

S. Barton Babbage is Principal of Ridley College and Dean of St. Paul’s Cathedral in Melbourne, Australia. Previously he was Dean of St. Andrew’s Cathedral in Sydney. Among his published works are Puritanism and Richard Bancroft and Man in Nature and Grace. His sermons appear in several important compilations. Periodically he contributes an essay to this magazine’s “Review of Current Religious Thought.”