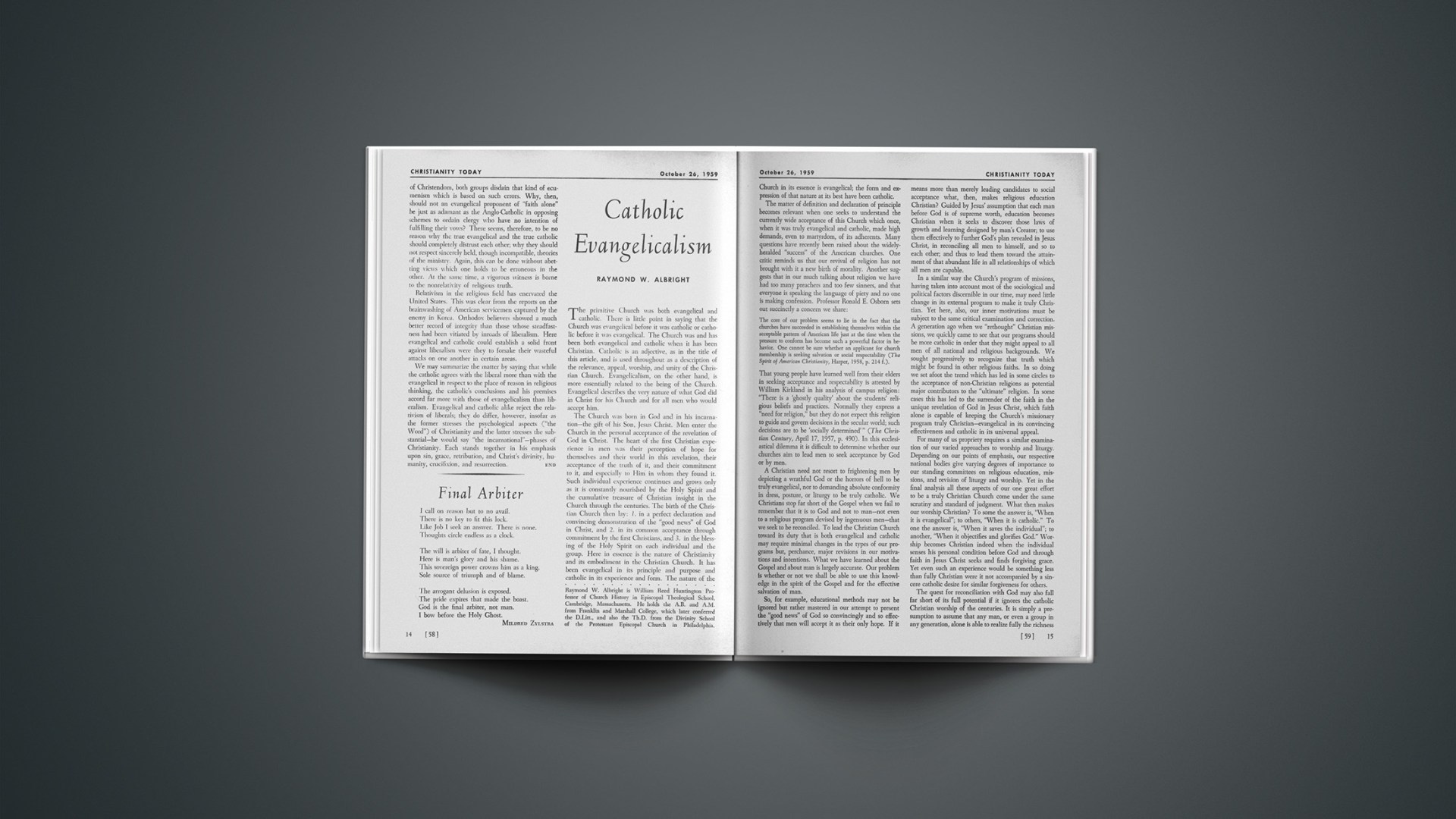

The primitive Church was both evangelical and catholic. There is little point in saying that the Church was evangelical before it was catholic or catholic before it was evangelical. The Church was and has been both evangelical and catholic when it has been Christian. Catholic is an adjective, as in the title of this article, and is used throughout as a description of the relevance, appeal, worship, and unity of the Christian Church. Evangelicalism, on the other hand, is more essentially related to the being of the Church. Evangelical describes the very nature of what God did in Christ for his Church and for all men who would accept him.

The Church was born in God and in his incarnation—the gift of his Son, Jesus Christ. Men enter the Church in the personal acceptance of the revelation of God in Christ. The heart of the first Christian experience in men was their perception of hope for themselves and their world in this revelation, their acceptance of the truth of it, and their commitment to it, and especially to Him in whom they found it. Such individual experience continues and grows only as it is constantly nourished by the Holy Spirit and the cumulative treasure of Christian insight in the Church through the centuries. The birth of the Christian Church then lay: 1. in a perfect declaration and convincing demonstration of the “good news” of God in Christ, and 2. in its common acceptance through commitment by the first Christians, and 3. in the blessing of the Holy Spirit on each individual and the group. Here in essence is the nature of Christianity and its embodiment in the Christian Church. It has been evangelical in its principle and purpose and catholic in its experience and form. The nature of the Church in its essence is evangelical; the form and expression of that nature at its best have been catholic.

The matter of definition and declaration of principle becomes relevant when one seeks to understand the currently wide acceptance of this Church which once, when it was truly evangelical and catholic, made high demands, even to martyrdom, of its adherents. Many questions have recently been raised about the widely-heralded “success” of the American churches. One critic reminds us that our revival of religion has not brought with it a new birth of morality. Another suggests that in our much talking about religion we have had too many preachers and too few sinners, and that everyone is speaking the language of piety and no one is making confession. Professor Ronald E. Osborn sets out succinctly a concern we share:

The core of our problem seems to lie in the fact that the churches have succeeded in establishing themselves within the acceptable pattern of American life just at the time when the pressure to conform has become such a powerful factor in behavior. One cannot be sure whether an applicant for church membership is seeking salvation or social respectability (The Spirit of American Christianity, Harper, 1958, p. 214 f.).

That young people have learned well from their elders in seeking acceptance and respectability is attested by William Kirkland in his analysis of campus religion: “There is a ‘ghostly quality’ about the students’ religious beliefs and practices. Normally they express a “need for religion,” but they do not expect this religion to guide and govern decisions in the secular world; such decisions are to be ‘socially determined’ ” (The Christian Century, April 17, 1957, p. 490). In this ecclesiastical dilemma it is difficult to determine whether our churches aim to lead men to seek acceptance by God or by men.

A Christian need not resort to frightening men by depicting a wrathful God or the horrors of hell to be truly evangelical, nor to demanding absolute conformity in dress, posture, or liturgy to be truly catholic. We Christians stop far short of the Gospel when we fail to remember that it is to God and not to man—not even to a religious program devised by ingenuous men—that we seek to be reconciled. To lead the Christian Church toward its duty that is both evangelical and catholic may require minimal changes in the types of our programs but, perchance, major revisions in our motivations and intentions. What we have learned about the Gospel and about man is largely accurate. Our problem is whether or not we shall be able to use this knowledge in the spirit of the Gospel and for the effective salvation of man.

So, for example, educational methods may not be ignored but rather mastered in our attempt to present the “good news” of God so convincingly and so effectively that men will accept it as their only hope. If it means more than merely leading candidates to social acceptance what, then, makes religious education Christian? Guided by Jesus’ assumption that each man before God is of supreme worth, education becomes Christian when it seeks to discover those laws of growth and learning designed by man’s Creator; to use them effectively to further God’s plan revealed in Jesus Christ, in reconciling all men to himself, and so to each other; and thus to lead them toward the attainment of that abundant life in all relationships of which all men are capable.

In a similar way the Church’s program of missions, having taken into account most of the sociological and political factors discernible in our time, may need little change in its external program to make it truly Christian. Yet here, also, our inner motivations must be subject to the same critical examination and correction. A generation ago when we “rethought” Christian missions, we quickly came to see that our programs should be more catholic in order that they might appeal to all men of all national and religious backgrounds. We sought progressively to recognize that truth which might be found in other religious faiths. In so doing we set afoot the trend which has led in some circles to the acceptance of non-Christian religions as potential major contributors to the “ultimate” religion. In some cases this has led to the surrender of the faith in the unique revelation of God in Jesus Christ, which faith alone is capable of keeping the Church’s missionary program truly Christian—evangelical in its convincing effectiveness and catholic in its universal appeal.

For many of us propriety requires a similar examination of our varied approaches to worship and liturgy. Depending on our points of emphasis, our respective national bodies give varying degrees of importance to our standing committees on religious education, missions, and revision of liturgy and worship. Yet in the final analysis all these aspects of our one great effort to be a truly Christian Church come under the same scrutiny and standard of judgment. What then makes our worship Christian? To some the answer is, “When it is evangelical”; to others, “When it is catholic.” To one the answer is, “When it saves the individual”; to another, “When it objectifies and glorifies God.” Worship becomes Christian indeed when the individual senses his personal condition before God and through faith in Jesus Christ seeks and finds forgiving grace. Yet even such an experience would be something less than fully Christian were it not accompanied by a sincere catholic desire for similar forgiveness for others.

The quest for reconciliation with God may also fall far short of its full potential if it ignores the catholic Christian worship of the centuries. It is simply a presumption to assume that any man, or even a group in any generation, alone is able to realize fully the richness of Christian worship. Although both factors have significance in Christian worship, it is not enough that some individual shall have found peace with God or that others shall have dressed, sung, and prayed as did the Christians of the earlier centuries. While the way of doing things is important, it is not as important as the thing to be done. While the reconciliation of man to God is desired, it is not enough unless in it all God is glorified. In our experience before God we may be aided indeed when we learn how others were confronted by him through the centuries; but all this may be useless unless it becomes significant for living individuals and leads us today to receive the benediction of his grace. Such Christian worship is evangelical and catholic.

That the true Christian Church is catholic is second only in importance to the fact that it is evangelical. These two qualities of Christianity are mutually dependent and supportive. The “good news” of God may be heard by all men and seen by all in the record of the mighty acts of God. But a religious experience does not become a Christian experience until the Gospel, on the evidence of the mighty acts of God, is individually accepted as the truth and adopted as a personal faith by genuine commitment to it.

Our generation has observed a brilliant approach in depth to the problem of the nature of God’s revelation in Christ. Critical investigators of archaeological, biblical, and philosophical sources have made it possible for an intelligent person to know more about the truth of God’s revelation now than at any time since Jesus spoke to men. The essential message of the Gospel is clear. The Church knows enough to be really evangelical.

In similar manner we have come in the past generation to know more about the nature of man, his patterns of conduct and motivations for action, than at any time since man has been man. Though these patterns vary, and motivations run the gamut from complete and violently supported selfishness to disinterested altruism, these acts of men fall into discernible patterns and the known substructure underlying all human motivations clearly indicates our common universal need. In a word, all men are still human and, no matter what our level of achievement, we still stand before God in common need of salvation from sin through the saving grace revealed by God in Jesus Christ.

Whether the Christian Church, with her comprehensive knowledge of the Gospel, can transmit the “good news” to men, whom she understands better than ever before, and in such a fashion that we all confess our sins before God more sincerely and receive his forgiveness more effectively, remains to be seen. This may be just possible if we remember that Jesus commanded his Church to be evangelical as well as catholic. Men have usually become Christian by personal commitment to Jesus before they have discovered an expression of faith in catholic symbols, common liturgies, or accepted customs. But there is absolutely no guarantee that critical and technologically skilled approaches to biblical, symbolic, or liturgical sources will produce a more effective evangelicalism. This will depend, indeed, not upon the tools employed, or even the keenness of those tools, but rather on the persons using them. Such alert persons, who by personal commitment to Jesus Christ are possessed of a power greater than themselves, the Holy Spirit, God’s contemporary presence among men, may be able to accomplish the Christian evangelical mission in the world through the Church. The experience of personal commitment without the support of the latter stabilizing factors may indeed be reckless; the attempt to give inflexible conformity to uniform though ancient practices without a personal experience of Jesus Christ is presumptuous. Together the truly irenic evangelical and catholic spirits may yet make our churches more Christian.

Raymond W. Albright is William Reed Huntington Professor of Church History in Episcopal Theological School, Cambridge, Massachusetts. He holds the A.B. and A.M. from Franklin and Marshall College, which later conferred the D.Litt., and also the Th.D. from the Divinity School of the Protestant Episcopal Church in Philadelphia.

Preacher In The Red

NIGHT WALKER

To keep a weekend engagement, the train deposited me at a country station 11 miles from Reading on a Saturday evening in December.

I found Mrs. Green’s cottage two miles from the station.

“Take off your wet shoes and put my late husband’s slippers on. He died 12 months ago tonight.”

After supper, during which a detailed account of the good man’s homegoing was recited, Mrs. Green showed me to my bedroom from which her husband passed away 12 months ago, tonight. “I don’t sleep here since that sad occasion,” explained my hostess. “I go to my neighbors. You are not afraid?”

“No, I shall be all right.” She went with a sombre “Good night.” I heard her lock the door. Whilst in bed thinking things over, and just about to doze off, I heard shuffling footsteps on the stairs. The door opened and a tall, gauntly draped figure appeared in the pale moonlight. The bedclothes at the foot of the bed were lifted. A bony hand gripped one of my feet, released it, gripped the other, and then pulled the clothes back over and left the room. Was I dreaming? I was too dazed to speak!

How pleased I was to hear Mrs. Green humming: “Brief life is here our portion,” as she poked the fire the next morning. “Ah!” she said as I entered the kitchen, “I do hope you passed a good night.” Then she added before I could answer, “I was very concerned about you last night. I had forgotten to put a hot water bottle in your bed, so I came over and felt your feet. They were warm, so I was content.”

“Ah! Sister Green,” I said, “you are kind.”

Ye fearful saints, when so distressed, ’Tis Sister Green who’ll do her best.—The REV. J. WILLIAMS, Cinderford, Gloucester, England.