You search the scriptures, because you think that in them you have eternal life; and it is they that bear witness to me; yet you refuse to come to me that you may have life” (John 5:39, 40, RSV).

The two most important questions which must be asked and answered about the Bible concern its origin and its purpose. Where has it come from, and what is it meant for? Until we know whether its origin is ultimately human or divine, we cannot determine what degree of confidence may be placed in it. Until we have clarified the purpose for which its divine Author or human authors brought it into being, we cannot put it to right and proper use.

Both questions gain an answer from the words of Jesus to certain Jews, recorded in chapter 5 of John’s Gospel, verses 39 and 40: “You search the scriptures, because you think that in them you have eternal life; and it is they that bear witness to me; yet you refuse to come to me that you may have life” (RSV). He was, of course, referring primarily to the Old Testament Scriptures. But if we concede that there is an organic unity in the Bible, and that God intended his saving acts to be recorded and interpreted under the New Covenant as much as under the Old, then these words may be applied to the New Testament also.

THE SCRIPTURES HAVE A DIVINE ORIGIN

The divine origin of the Scriptures is clearly implied in our Lord’s statement: “it is they that bear witness to me.” The scriptural witness to him is a divine witness. Jesus has been advancing some stupendous claims about his relation to the Father. The Father has committed to him the two tasks of judging and quickening (vv. 21, 22, 27, 28). But how are Christ’s claims to be confirmed? They are confirmed, he says, by testimony, and the testimony he requires adequately to authenticate his claims is divine, not human. Self-testimony is not enough. “If I bear witness to myself, my testimony is not true” (v. 31, RSV). John the Baptist’s testimony is not enough. “You sent to John, and he has borne witness to the truth” (v. 33). No. He adds: “Not that the testimony which I receive is from man” (v. 34). “There is another who bears witness to me, and I know that the testimony which he bears to me is true” (v. 32). He is referring, of course, to the Father. But how does the Father bear witness to the Son? In two ways; first, in the works of Jesus, and second, in the words of Scripture. “The testimony which I have is greater than that of John; for the works which the Father has granted me to accomplish, these very works which I am doing, bear me witness that the Father has sent me” (v. 36). This is familiar ground to readers of the Fourth Gospel. “If I am not doing the works of my Father, then do not believe me; but if I do them, even though you do not believe me, believe the works, that you may know and understand that the Father is in me and I am in the Father” (10:27, 38). “Believe me that I am in the Father and the Father in me; or else believe me for the sake of the works themselves” (14:11).

Our Lord asserts, however, that he has from the Father an even more direct testimony than his mighty works. “And the Father who sent me has himself borne witness to me” (5:37). But these Jews were rejecting this testimony. “You do not have his word abiding in you, for you do not believe him whom he has sent” (v. 38). What is this witness? Where is this word? Jesus immediately continues, “You search the scriptures … and it is they that bear witness to me” (v. 39), and concludes this discourse with a specific example of what he means: “Do not think that I shall accuse you to the Father; it is Moses who accuses you, on whom you set your hope. If you believed Moses, you would believe me, for he wrote of me. But if you do not believe his writings, how will you believe my words?” (vv. 45–47).

The Scriptures are, then, in the thought and teaching of Jesus, the supreme testimony of the Father to the Son. They are the word and witness of God. True, they had human authors. It was Moses who wrote, and the writings of Moses are the Word of God (vv. 46, 47, 38). Jesus undoubtedly believed the Bible to be no ordinary book, nor even a whole library of ordinary books, because behind the human writers stood the one divine Author, the Holy Spirit of God, who, as the Nicene Creed affirms, “spake by the prophets.” Because men spoke from God, or God spoke through men (for the process of inspiration is described in both ways in Scripture), the Bible is to be viewed not as a mere symposium of human words but as the very Word of God.

There are many grounds for this Christian belief. There is the Scriptures’ own unaffected claim. There is their astonishing unity of theme, despite the extremely varied circumstances of composition. There is their power to convict and convert, to comfort and uplift, to inspire and to save. But the greatest and firmest ground for faith in the divine origin of Scripture will always remain that Jesus himself taught it. The living Word of God bore witness to the written Word of God. His opinion of, and attitude to, the Scriptures is not difficult to determine. Three striking indications are:

He Believed Them. Let one example suffice. On the way to the Mount of Olives he turned to the disciples and said: “You will all fall away.” This categorical statement must have amazed and perplexed them. Had they not sworn allegiance to him and promised to be true to him? Had they not followed him these three years without thought of home and comfort and security? How could he assert with such definiteness and dogmatism that every one of them would desert him? The answer is simple. He continues: “You will all fall away; for it is written, “I will strike the shepherd, and the sheep will be scattered” (Mark 14:27). It is because the Scriptures had said so that he knew beyond peradventure or doubt that it would come to pass.

It is for this reason that the progress of events at the end of his career did not take him by surprise. He knew that what had been written about him would have its fulfillment. The word gegraptai, “it stands written,” was enough to remove every doubt and silence every objection. So, with an assurance and clarity that over-awed the Twelve, he repeatedly predicted both his death and his resurrection, because the Old Testament had depicted the sufferings and the glory of the Christ. So plain was it to him that he soundly rebuked the Emmaus disciples after the resurrection, saying: “O foolish men, and slow of heart to believe all that the prophets have spoken! Was it not necessary that the Christ should suffer these things and enter into his glory? And beginning with Moses and all the prophets, he interpreted to them in all the scriptures the things concerning himself” (Luke 24:25–27).

No wonder he could say in his Sermon on the Mount, “Truly, I say to you, till heaven and earth pass away, not an iota, not a dot, will pass from the law until all is accomplished” (Matt. 5:18) and, again, later: “Scripture cannot be broken” (John 10:35). To him the Scriptures were unbreakable because they are eternal. It was impossible that one Scripture should fail or pass until it had been fulfilled.

He Obeyed Them. Even more impressive than the fact that Jesus believed the Scriptures is that he obeyed them in his own life. He practiced what he preached. He not only said he believed in their divine origin; he acted on his belief by submitting to their authority as to the authority of God. He gladly and voluntarily accepted a position of humble subordination to them. He followed their teaching in his own life.

The most striking example of this occurs during the period of temptation in the wilderness. The synoptic evangelists record the three principal temptations with which he must later have told them he had been assaulted. Each time he countered the devil’s proposal with an apt quotation from chapters 6 or 8 of the Book of Deuteronomy, on which he appears to have been meditating at the time. It is incorrect to say that he quoted Scripture at the devil. What he was actually doing was quoting Scripture at himself in the hearing of the devil. For instance, when he said, “It is written, ‘Thou shalt worship the Lord thy God, and him only shalt thou serve,’ ” or “It is written, ‘Thou shalt not tempt the Lord thy God,’ ” he was not telling Satan what to do and what not to do. He was not commanding Satan to worship God and forbidding Satan to tempt God. No. He was stating what he himself would and would not do. It was his firm resolve to worship exclusively, he said, and not to tempt God in unbelief. Why? Because this was what was written in the Scriptures. Once again, the simple word gegraptai, “it stands written,” settled the issue for him. What was written was as much the standard of his behavior as the criterion of his belief.

Moreover, Jesus obeyed the Scriptures in his ministry as well as in his private conduct. The Old Testament set forth the nature and character of the mission he had come to fulfill. He knew that he was the anointed King, the Son of man, the suffering servant, the smitten shepherd of Old Testament prophecy, and he resolved to fulfill to the letter what was written of him. Thus, “the Son of man goes as it is written of him” (Mark 14:21), and again, “Behold, we are going up to Jerusalem, and everything that is written of the Son of man by the prophets will be accomplished” (Luke 18:31).

Indeed, Jesus felt a certain compulsion, to which he often referred, to conform his ministry to the prophetic pattern. Even as a boy of 12, this sense of necessity had begun to grip him: “Did you not know that I must be in my Father’s house?” What is the meaning of this “must”? We hear it again and again. It was the compulsion of Scripture, the inner constraint to fulfill the messianic role which he found portrayed in the Old Testament and which he had voluntarily assumed. So, “He began to teach them that the Son of man must suffer many things” (Mark 8:31). “I must work the works of him that sent me while it is day” (John 9:4). When Peter attempted to defend him in the garden and prevent his arrest, he forbade him, saying: “how then should the scriptures be fulfilled, that it must be so?” (Matt. 26:54). Again, “Was it not necessary that the Christ should suffer these things?” (Luke 24:26).

He Quoted Them. Not only did Jesus believe the statements and obey the commands of Scripture in his own life, but he made the Scriptures the standard of reference when engaged in debate with his critics. To him the Scriptures were the arbiter in every dispute, the canon (literally, a carpenter’s rule) to measure and judge what was under discussion, the criterion by which to test every idea. He made the Scriptures the final court of appeal.

This can be seen from his attitude to the religious parties of his day, the Sadducees and the Pharisees.

When the Sadducees (who denied the immortality of the soul, the resurrection of the body, and the existence of spirits and angels) came to him with their trick question about the condition in the next world of a woman married and widowed seven times, he replied: “You do greatly err” or (RSV) “Is not this why you are wrong, that you know neither the scriptures nor the power of God?” (Mark 12:24). He went on to refute them, not only in the silly problem they had propounded to him, but in their whole theological position, by quoting Exodus 3:6 and expounding its implications.

As for the Scribes and Pharisees, Jesus rejected their innumerable man-made rules and traditions and referred them back to the simple, unadulterated Word of God. Whether the question was sabbath observance, ceremonial laws, or marriage and divorce, it was to the original divine Word that he made his appeal. You make the word of God void by your tradition, he said, and “You have a fine way of rejecting the commandment of God, in order to keep your tradition!” (Mark 7:13, 9). And during the Sermon on the Mount, in the six paragraphs introduced by the formula “You have heard that it hath been said … but I say to you.…” Jesus is contradicting not the law of Moses but the unwarranted scribal interpretations of Moses’ law. This is clear from the fact that he has just said “Think not that I have come to abolish the law and the prophets; I have come not to abolish them but to fulfill them” (Matt. 5:17). Besides, where does the law say “You shall love your neighbour and hate your enemy” (v. 43)? The law says “Thou shalt love thy neighbour.” It was the Scribes who attempted to restrict the reference of this command to friends and kinsmen, and Jesus rejected their interpretation.

All of this is of the greatest importance. Jesus of Nazareth, the Son of God, with all his supernatural knowledge and wisdom, accepted and endorsed the divine origin and authority of the Old Testament Scriptures. He believed them. He obeyed them in his own life and ministry. He quoted them in debate and controversy. The question is, are we to regard lightly the Scriptures to which he gave his reverent assent? Can we repudiate what he embraced? Are we really prepared to part company with him on this issue and assert that he was mistaken? No. He who said “I am the truth” undoubtedly spoke the truth. If he taught that the Scriptures were a divine word and witness, the Christian is committed to believe this. Never mind, in the last resort, what the rationalists and the critics say, or even what the theologians and the churches say. What matters to us supremely is: What did Jesus Christ say?

THE SCRIPTURES HAVE A PRACTICAL PURPOSE

We have considered the origin of the Scriptures; we must now consider their purpose. We have seen from whom they have come to us; we must now ask for what they have been given. It is important to grasp that their purpose is not academic but practical. No doubt the Scriptures contain both science and history, but their purpose is neither scientific nor historical. The Bible also includes great literature and profound philosophy, but its purpose is neither literary nor philosophical. The so-called “Bible Designed to be Read as Literature” is a most misleading volume, for the Bible never was designed to be read as literature. The Bible is not an academic textbook for any branch of knowledge, so much as a practical handbook of religion. It is a lamp to our feet and a light to our path.

This Jesus made plain in the verses we are studying. “You search the scriptures, because you think that in them you have eternal life; and it is they that bear witness to me; yet you refuse to come to me that you may have life.” The Jews were in the habit of “searching the scriptures.” The verb used here, comments Bishop B. F. Westcott, indicates “that minute, intense investigation of Scripture which issued in the allegorical and mystical interpretations of the Midrash.” They thus studied and sought to expound the Scriptures, while fondly imagining that salvation and eternal life were to be found in accurate knowledge!

But the purpose of the Scriptures is not merely to impart knowledge, but to bestow life. Knowledge is important, but as a means to an end, not as an end in itself. The holy, God-breathed Scriptures, wrote Paul to Timothy, “are able to make thee wise unto salvation through faith in Christ Jesus” (2 Tim. 3:15, 16). Their purpose is not just to “make wise” but to “make wise unto salvation” and that “through faith in Christ Jesus.” Their ultimate purpose is to lead to salvation; their immediate purpose is to arouse personal faith in Christ in whom salvation is to be found. This, albeit in different terms, is exactly what Jesus in John 5:39, 40 is recorded as saying. Three stages are discernible in the purpose of Holy Scripture.

The Scriptures Point to Christ. “It is they which bear witness to me,” he said. The Old Testament points forward, and the New Testament looks back, to Jesus Christ. English theologians of a former generation were fond of saying that as in England every track and lane and road, linking on to other thoroughfares, would ultimately lead the traveler to London, so every verse in Scripture, leading to other verses, would ultimately bring the reader to Christ. Or we might say that as seven or eight different streets converge on Piccadilly Circus in the heart of London, so all the prophetic and apostolic strands of biblical witness converge on Jesus Christ. He is the grand theme of Holy Scripture. Reading the Bible is like an exciting treasure hunt. As each clue leads to another clue until the treasure is discovered, so every verse leads to other verses until the glory of Christ is unveiled. The eye of faith, wherever it looks in Scripture, sees him, as he expounds to us “in all the scriptures the things concerning himself” (Luke 24:27; cf. v. 44). We see him foreshadowed in the Mosaic sacrifices and in the Davidic Kingdom. The law is our schoolmaster to bring us to Christ, and the prophets write of his sufferings and glory. The evangelists describe his birth, life, death, and resurrection, his gracious words and mighty works; the Acts reveals him continuing through his Spirit what he had begun to do and to teach in the days of his flesh; the apostles unfold the hidden glory of his person and work; while in the Revelation we see him worshipped by the hosts of heaven and finally overthrowing the powers of evil. No man can read the Scriptures without being brought face to face with Jesus, the Son of God and Saviour of men. This is why we love the Bible. We love it because it speaks to us of him.

The Scriptures Affirm that Life Is to be Found in Christ. The purpose of the Scriptures is not just to reveal Christ, but to reveal him as the only Saviour competent to bring forgiveness to sinners, secure their reconciliation to God and make them holy. That is why they concentrate on his “suffering and glory.” The Gospel they enshrine is that “Christ died for our sins in accordance with the scriptures, that he was buried, that he was raised on the third day in accordance with the scriptures, and that he appeared …” (1 Cor. 15:3–5). As Dr. Marcus Dodds writes in the Expositor’s Greek Testament, the Scriptures “do not give life; they lead to the Lifegiver.” This is what our Lord meant in saying that the Jews thought they could find life in the Scriptures and would not come to him that they might receive life. Of every Scripture, and not just of the Fourth Gospel, it may be said: “These are written that you may believe that Jesus is the Christ the Son of God, and that believing you may have life in his name” (John 20:31).

The Scriptures Invite Us to Come to Christ to Receive Life. The Scriptures do not just point; they urge us to go to the One to whom they point. They do not only make an offer of life; they issue a challenge to action. What the star did for the Magi, the Scriptures do for us. The star beckoned and guided them to Jesus; the Scriptures will lighten our path to him. That is why Jesus blamed his contemporaries for not coming to him. Their study of the Scriptures was purely academic. They were not doers of the Word, but hearers only and thus self-deceived. They searched the Scriptures, but did not obey them. Indeed, they would not come to Christ to receive life. Their minds may have been busily investigating, but their wills were stubborn and inflexible.

We must come to the Bible as sick sinners. It is no use just memorizing its prescription for salvation. We must go to Christ and take him as the medicine our sick souls need.

These verses from John 5 show our Lord’s view of the divine origin and practical purpose of the Scriptures. We learn their divine origin from his testimony to them. We learn their practical purpose from their testimony to him. There is therefore between Christ (the living Word of God) and the Scriptures (the written Word of God) this reciprocal testimony. Each bears witness to the other. It is because he bore witness to them that we accept their divine origin. It is because they bear witness to him that we fulfill their practical purpose, come to him in personal faith, and receive life. May God grant in his infinite mercy that Jesus may never have to say to us what he said to his contemporaries: “You search the scriptures, because you think that in them you have eternal life; and it is they that bear witness to me; yet you refuse to come to me that you may have life.”

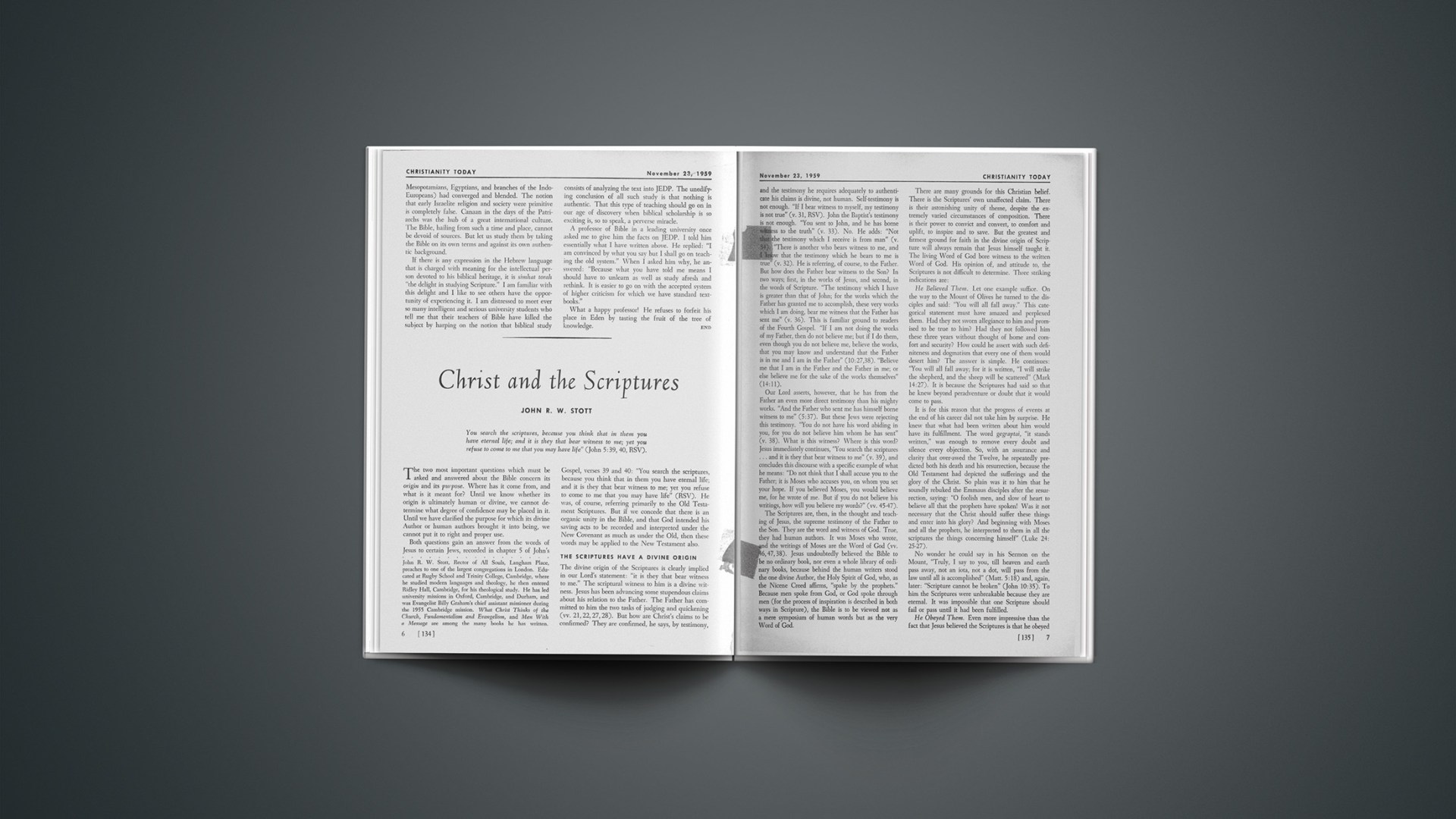

John R. W. Stott, Rector of All Souls, Langham Place, preaches to one of the largest congregations in London. Educated at Rugby School and Trinity College, Cambridge, where he studied modern languages and theology, he then entered Ridley Hall, Cambridge, for his theological study. He has led university missions in Oxford, Cambridge, and Durham, and was Evangelist Billy Graham’s chief assistant missioner during the 1955 Cambridge mission. What Christ Thinks of the Church, Fundamentalism and Evangelism, and Men With a Message are among the many books he has written.