During the past 28 years 3,616 persons have been executed in the United States—3,136 for murder, 418 for rape, and 62 for other offenses such as treason, espionage, kidnapping, and bank robbery. Nine states (Alaska, Delaware, Hawaii, Maine, Michigan, Minnesota, North Dakota, Rhode Island, and Wisconsin) have set aside capital punishment, but all the others along with the District of Columbia impose the death penalty (including eight states which in time past abolished capital punishment only to reinstate it).

Churchmen have become increasingly vocal over the issue. One group contends that capital punishment is immoral, another argues that the death penalty for murder is not only permissible but mandatory because civil government is under divine obligation.

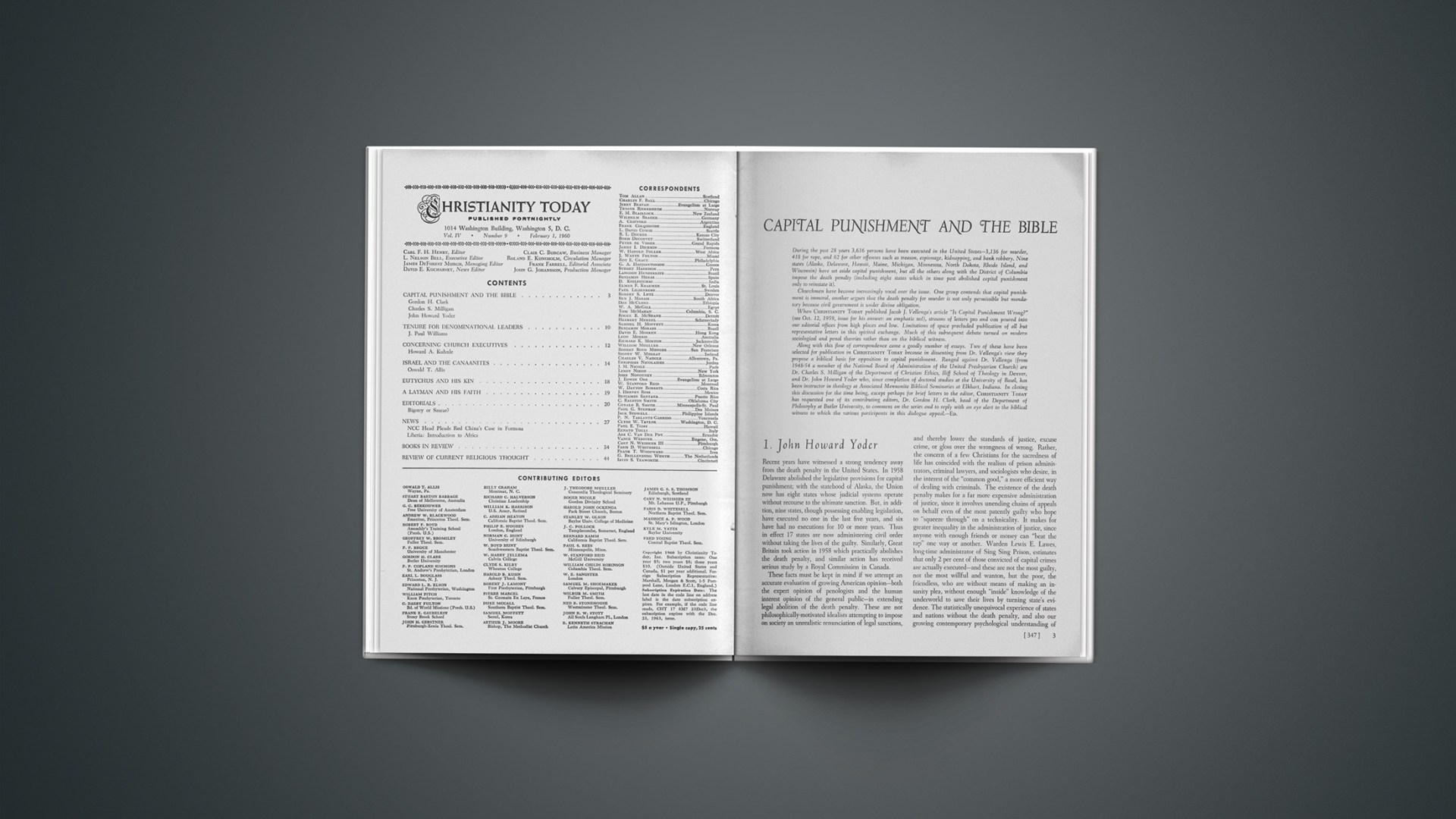

WhenCHRISTIANITY TODAYpublished Jacob J. Vellenga’s article “Is Capital Punishment Wrong?” (see Oct. 12, 1959, issue for his answer: an emphatic no!), streams of letters pro and con poured into our editorial offices from high places and low. Limitations of space precluded publication of all but representative letters in this spirited exchange. Much of this subsequent debate turned on modern sociological and penal theories rather than on the biblical witness.

Along with this flow of correspondence came a goodly number of essays. Two of these have been selected for publication inCHRISTIANITY TODAYbecause in dissenting from Dr. Vellenga’s view they propose a biblical basis for opposition to capital punishment. Ranged against Dr. Vellenga (from 1948–54 a member of the National Board of Administration of the United Presbyterian Church) are Dr. Charles S. Milligan of the Department of Christian Ethics, Iliff School of Theology in Denver, and Dr. John Howard Yoder who, since completion of doctoral studies at the University of Basel, has been instructor in theology at Associated Mennonite Biblical Seminaries at Elkhart, Indiana. In closing this discussion for the time being, except perhaps for brief letters to the editor, CHRISTIANITY TODAYhas requested one of its contributing editors, Dr. Gordon H. Clark, head of the Department of Philosophy at Butler University, to comment on the series and to reply with an eye alert to the biblical witness to which the various participants in this dialogue appeal.—ED.

1. John Howard Yoder

Recent years have witnessed a strong tendency away from the death penalty in the United States. In 1958 Delaware abolished the legislative provisions for capital punishment; with the statehood of Alaska, the Union now has eight states whose judicial systems operate without recourse to the ultimate sanction. But, in addition, nine states, though possessing enabling legislation, have executed no one in the last five years, and six have had no executions for 10 or more years. Thus in effect 17 states are now administering civil order without taking the lives of the guilty. Similarly, Great Britain took action in 1958 which practically abolishes the death penalty, and similar action has received serious study by a Royal Commission in Canada.

These facts must be kept in mind if we attempt an accurate evaluation of growing American opinion—both the expert opinion of penologists and the human interest opinion of the general public—in extending legal abolition of the death penalty. These are not philosophically-motivated idealists attempting to impose on society an unrealistic renunciation of legal sanctions, and thereby lower the standards of justice, excuse crime, or gloss over the wrongness of wrong. Rather, the concern of a few Christians for the sacredness of life has coincided with the realism of prison administrators, criminal lawyers, and sociologists who desire, in the interest of the “common good,” a more efficient way of dealing with criminals. The existence of the death penalty makes for a far more expensive administration of justice, since it involves unending chains of appeals on behalf even of the most patently guilty who hope to “squeeze through” on a technicality. It makes for greater inequality in the administration of justice, since anyone with enough friends or money can “beat the rap” one way or another. Warden Lewis E. Lawes, long-time administrator of Sing Sing Prison, estimates that only 2 per cent of those convicted of capital crimes are actually executed—and these are not the most guilty, not the most willful and wanton, but the poor, the friendless, who are without means of making an insanity plea, without enough “inside” knowledge of the underworld to save their lives by turning state’s evidence. The statistically unequivocal experience of states and nations without the death penalty, and also our growing contemporary psychological understanding of the motivation of murderers, further make it clear that the death penalty has no deterrent effect on potential murderers.

Some of the moral aspects of the practice of killing criminals have also contributed to the current reappraisal. Capital punishment presupposes an infallible judicial procedure, lest it kill the innocent rather than the guilty. Yet no judicial procedure is flawless. The number of condemnations of innocent persons, being the result of mistaken identification, misinterpreted circumstantial evidence, emotional susceptibilities of juries, and other understandable “human factors,” is estimated to run as high as 5 per cent. We should not condemn our judicial systems for the fact that errors happen, but the moral justification of the death penalty is singularly weakened if the factor of human error is faced. Similarly, our growing understanding of psychological processes discloses that the problem of “accountability” is much more complex than was once supposed when one or two questions were thought adequate to establish a culprit’s “sanity” and thereby his responsibility. Likewise we are now less self-righteous about society’s share of the “blame” for crime. If society—family, neighborhood, and nation—deprives a child of affection, teaches him vice through the world’s largest pornographic industry, glorifies violence through the entertainment industry, glorifies crime through the wealth it gives its gangster kings, and shuts off legitimate avenues of growth and self-expression through substandard schooling and ethnic segregation, and then this child becomes a teen-ager armed with a knife and excited by alcohol and other narcotics which society permits to be sold to him, is not society’s casting the blame on the teen-ager a disgraceful search for a scapegoat? Such insistence on “personal responsibility” may well be a mere screen for society’s refusal to face its moral decadence in repentant honesty.

These observations are not humanistic theories or vague utopian philosophies; they are realities to which God’s Word speaks. The evangelical battlecry, sola scriptura, does not mean that the Bible is a substitute for the facts but rather that it is the only authoritative source of light to throw on the facts. To turn piously to “the Bible alone” before having faced the problems for which answers from Scripture are needed is to make oneself blind to one’s own extra-scriptural assumptions. Understandably but regrettably, some conservative evangelicals are tempted toward this kind of obscurantism, and go on treating the issue of capital punishment as if the advocates of abolition were challenging civil government, whitewashing crime, and tearing the Sixth Commandment from its context.

As we seek the light of God’s Word, the first issue we must face is one of hermeneutics: how are we to understand the relationship between the Old and New Testaments? Does Christ simply complete the Old Testament so that a proper Christian understanding of any problem begins with Moses? Or does he tell us how to read the Old Testament so that a proper approach to the Bible begins with Christ himself? In spite of theoretical affirmations of the centrality of Christ and the finality of the New Covenant, the history of Protestant and Catholic thought on the question of civil order has been overwhelmingly dominated by approaches which consider the Old, not the New, Testament to be fundamental. In effect, this does not mean even that the two Testaments are placed on the same level; for the Old speaks directly to the issue of civil order, and the New speaks to it only obliquely, with the result that in application the Old is placed above the New. This is the real hermeneutic significance of the position of most of those who try to justify the death penalty by “what Scripture actually teaches.”

The first shortcoming of this approach is that none of those who advocate it are interested in following it consistently. It is cited where it favors the argument, and dropped where inconvenient. To apply consistently this approach to Old Testament prescriptions concerning the social order would mean that the death penalty should also apply to animals (Gen. 9:5; Exod. 21:28), to witches, and to adulterers. When it is exacted for manslaughter, the executioner should be the victim’s next of kin; there need be no due process of law, but there should be cities of refuge for the innocent and those guilty of unintentional killing. And while trying in this way to “take the Bible seriously,” the disputant can offer no logical reason for respecting less its prescriptions on the sabbath, the cure for leprosy, slavery, and the economic order.

The manifest impossibility of honestly applying such an hermeneutic is not the primary argument against it, however. The fact is that at two significant points the New Testament directly modifies the teaching of the Old. One of these points is the spiritual understanding of what it means to be God’s people. In the Old Testament, at least in the period to which the civil regulations of the Pentateuch relate, the ethnic, civil, geographic, and religious communities were one. The New Covenant changed this. Being a son of Abraham is a matter of faith, not of linear descent (Matt. 3:9; John 8:39 ff.; Gal. 3:9), and the civil order is in the hands of pagan authorities. All of this so shifts the context of social-ethical thought that a simple transposition of Old Testament prescriptions would be illegitimate even if it were possible.

There is, nonetheless a stronger reason for challenging the finality of Israelite law. The ultimate basis of the death penalty in Genesis 9 was not civil, that is, in the narrow modern sense of serving the maintenance of order in society or the punishment of the guilty. It was expiatory. Killing men and consuming the blood of animals are forbidden in the same sentence, for creaturely life belongs in the realm of the “holy” (in the original cultic sense of the term). Life is God’s peculiar possession which man may not profane with impunity. Thus the function of capital punishment in Genesis 9 is not the defense of society but the expiation of an offense against the Image of God. If this be the case then—and both exegetical and anthropological studies confirm strongly that it is—then the central events of the New Testament, the Cross and the Resurrection, are overwhelmingly relevant to this issue. The sacrifice of Christ is the end of all expiatory killing; only an unbiblical compartmentalization can argue that the event of the Cross, itself a typical phenomenon of miscarried civil justice issuing in the execution of an innocent, has nothing to do with the civil order.

THE LAW OF LOVE

If then Judaism is not an adequate key to the understanding of the Bible’s teaching on human life, what is the key? Is it not to be found in the frequent New Testament teaching, especially clear in Matthew 25:31 ff. and in 1 John 3:18; 4:12, 20, that we are to see and serve God in our neighbor? Countless other New Testament admonitions tell us to love our neighbor and to keep God’s commandments. Furthermore they define what loving our neighbor means. The idea that we could kill his body while loving his soul is excluded. Love considers the total well-being of the beloved: “love worketh no ill” (Rom. 13). This divinely sanctioned worth which my neighbor should have in my eyes is due not to some philosophical idea of inherent human dignity but to the grace of creation and the impartation of the divine Image, and to the reaffirmation of this grace in the Incarnation and the teaching and behavior of our Lord. Bodily life is not simply a carnal vehicle for the immortal soul; it is part and parcel of the unity of human personality through which the divine Word condescended to reveal himself.

The only direct New Testament reference to capital punishment is in John chapter 8, a passage generally recognized to be authentic Gospel tradition even by those who deny its belonging in the original canonic text of John. Romans 13 deals with the principle that Christians should submit to the established pagan civil authorities. It affirms that even they are instituted to serve the “good” (v. 4). This text alone, however, does not spell out what “good” is. The “sword” of which Paul writes is the symbol of judicial authority; it is not the instrument used by the Romans for executing criminals. Even if it were, the passage would say nothing of the tempering effect which the leaven of Christian witness within society should have on its institutions. Neither the passage in Romans nor comparable ones in the epistles of Timothy or Peter speak to the issue of the state’s taking life; and the incident from the life of Jesus remains our first orientation point.

The striking thing about the attitude Jesus takes to the woman, patently guilty of a capital offense, is not what he says about capital punishment but the new context into which he places the problem. He does not deny that such prescriptions were part of the Mosaic code, but he raises two other considerations which profoundly modify the significance of that code for his day and for ours. First he raises the issue of the moral authority of judge and executioner: “Let him that is without sin cast the first stone.” Secondly he applies to this woman’s offense, which is a civil offense, his authority to forgive sin. There is no differentiation between the religious and the civil which says that God may forgive the sinner but justice must still be done. Once again we see that the expiation wrought by Christ is politically relevant. Like divorce (Matt. 19:8), like the distortions of the law which Jesus corrects in Matthew 5, and like the institution of slavery, capital punishment is one of those infringements on the divine Will which take place in society, sometimes with a certain formal legitimacy, and which the Gospel does not immediately eliminate from secular society even though it declares that “from the beginning it was not so.” The new level of brotherhood on which the redeemed community is to live cannot be directly enforced upon the larger society; but if it be of the Gospel, it must work as a leaven, as salt, and as light, especially if, as in the case in the Anglo-Saxon world, the larger society claims some kind of Christian sanction for its existence and its social pattern. If Christ is not only Prophet and Priest but also King, the line between Church and world cannot be impermeable to moral truth. Something of cross-bearing, forgiving ethics of the Kingdom must be made relevant to the civil order.

This relevance will not be direct and immediate. The State is not and should not be the Church, and therefore it cannot apply New Testament ethics in an unqualified way. Yet to have made this point does not mean that the State may operate according to standards that contradict those of the Gospel. There is a difference between diluting, adapting, and qualifying standards which the State must do, and denying them altogether which the State has no right to do. To dispose of the life of fellowmen, who share with us the image of God and for whom Christ, being made in the likeness of men, died, oversteps the limits of the case which any government within “Christendom” can make for ethical compromise. The State is not made Christian by the presence of the Church in its population or by the presence of pious phrases on its postage stamps and coins. It has at least been made aware of and has partially committed itself to certain divine standards which it cannot ignore. If a given society permits slavery, divorce, and vengeance against criminals (most of the biblical arguments for capital punishment can be closely paralleled by similar ones for the institution of slavery), the Church cannot legally abolish these practices; but she can call the State to a closer approximation to true standards of human community.

The sanctity of human life is not a dogma of speculation, but part of the divine work of Creation and Redemption. We call for the legal abolition of capital punishment not because we think the criminal is innocent but because we share his guilt before God who has borne the punishment we all merited. Certainly we are not saying that he is a nice person worthy of another chance. It is God that gives another chance to the unworthy. We expect to do away with civil order, but Redemption has shown us what purpose that order serves and by what yardstick it should be measured. “I am come that they may have life” was not spoken only of men’s “souls.”

2. Charles S. Milligan

Dr. Jacob J. Vellenga raises the question, “Is Capital Punishment Wrong?” and answers that it is just and right. It is the conviction of many of us that his position is tragically mistaken. I will confine myself to Dr. Vellenga’s use of the Bible, because I believe it is at this point that an examination of his case causes it to collapse.

THE OLD TESTAMENT

There is certainly no question that the Old Testament permits, and indeed requires, the death penalty. What interests me about his citations from the Old Testament is that he limits them to those cases which have to do with murder. Now the fact is that the Old Testament includes many other crimes for which the death penalty is mandatory. The book of Exodus, for example, lists the following: to strike one’s father or mother (21:15), to steal and sell a man (21:16), and to curse one’s father or mother (21:17). If a man’s ox kills another man, the owner as well as the ox is to be killed (21:29). Witches are to be executed (22:18). Sacrifice to any god other than Jehovah is a capital crime (22:20). Leviticus adds adultery as a capital crime (20:10).

Nowhere does the Old Testament say that some of these laws are to be taken seriously and literally, while others may in time be ignored. It does not say that the principle of capital punishment is valid in general, and that each generation may determine the crimes to which it shall apply. On the contrary, the Old Testament is very explicit, as all codes of civil law must be, in spelling out the crimes and circumstances.

Not only are the crimes specified, but often we find the mode of punishment prescribed, and in some cases the person to carry out the execution. A wizard is to be stoned to death (Lev. 20:27). A woman assaulted in the city is to be stoned to death, but one assaulted in the country is not to be stoned (Deut. 22:24–25). This made sense in those days on the presumption that if the woman cried out in the city she would be heard, but she might cry out in the deserted fields and not be heard. Cities and houses are constructed differently today. A bride who is not a virgin is to be stoned to death by the elders in front of her father’s house (Deut. 22:21). A rebellious son is to be stoned to death by all the men of the city (Deut. 21:18–21).

Why does Dr. Vellenga not cite any of these references? They clearly bear on the question of capital punishment. I invite any reader to examine the vast literature on this subject and compare the careful attention given by abolitionists to arguments opposed to their case, as compared with like attention given by those who would retain capital punishment. The reader will find the comparison most extraordinary.

Now these laws I have cited seem to us very harsh. We should remember that when they were applied they represented a great advance over primitive custom. When observed they acted as a restraint upon angry vengeance. Indeed there are many situations in our world today where it would be pronounced and humane progress for only one life to be exacted for another, and only one tooth for another.

These laws were based upon a principle of exact retribution or just desert (Exod. 21:23–25). There were some exceptions: slaves, for example, did not merit equivalent retribution. A man whose servant dies from blows inflicted is to be punished, but it does not say he is to receive death (Exod. 21:20). If the owner puts out the slave’s eye, the slave does not have the right to put out the owner’s eye in return, but rather to go free, which in any case made more sense then than now (Exod. 21:26).

If you are going to insist that some of these laws be applied literally and mechanically to present day situations, I do not understand why all of them are not to be so applied. The Old Testament does not indicate that it is to be taken authoritatively on certain crimes but not on others nor on the method of execution. If you are going to follow a mechanical application of the Old Testament on capital punishment, I do not see any possible basis for objecting to polygomy (Deut. 21:15), animal sacrifices (Lev. 16:6), permitting the farm land to lie fallow every seventh year (Exod. 23:11), and avoiding the wearing of wool and linen at the same time (Deut. 22:11). I would remind those who use the Old Testament in this way that it was not only recommended but mandatory that a man have children by his brother’s widow (Deut. 25:5–10), which again served an important and quite possibly necessary purpose in those days.

THE NEW TESTAMENT

When we come to the New Testament, those who would justify capital punishment have a much harder time of it. Whereas Dr. Vellenga’s article was able to use the Old Testament directly and clearly, if with high selectivity, he found it necessary to engage in rather obscure reasoning when deducing from the New Testament that capital punishment is clearly justified.

Now I agree that Christ came to fulfill the law and, as Dr. Vellenga puts it, “not to destroy the basic principles of law and order, righteousness and justice.” But to say that is by no means to urge that the prescriptions of the Torah are to remain in force. This is just the point, that in the New Testament we move to a different base for law and therefore to some changes in specific laws and their mode of enforcement. The basic principle becomes very different from that of retribution which “worketh wrath” (Rom. 4:15). St. Paul plainly took the position that Christian faith cancels the prescriptions of the Torah (cf. Gal. 3:10–14; 3:23–25). As we all know, Jesus was frequently at odds with the Pharisees and Sadducees over rigid and exact following of the Old Testament prescriptions (cf. Matt. 12:10; 15:11–15; 21:23; 23:23; Mark 2:18; 2:24; 3:2; 7:5 ff.; Luke 5:33; 6:2; 14:3; and 20:2 to cite only a partial list.) “The law and the prophets were until John: since that time the kingdom of God is preached, and every man presseth into it” (Luke 16:16). This does not mean that the Old Testament becomes irrelevant, but it means freedom from the sort of selected proof texts which are cited to justify capital punishment.

And immediately following the statement that he came not to destroy the Torah, Jesus presented those immortal contrasts which provide a new way of looking at the whole matter (Matt. 5:17 ff.; cf. Luke 16:17). It can hardly be maintained, as one views the total context of the Gospels, that Jesus meant to commend a legalistic application of every prescription. When he summed up the law and the prophets, it was on the basis of love, not of paying back (Matt. 22:37–40). Christianity does not ask, “what is owed this man, that he may be paid exactly his due.” It asks, “how can this man be redeemed and his life reclaimed?” Is it significant that when Jesus read from the scroll of Isaiah in the synagogue, he stopped at that point where the passage goes on to speak of “the day of vengeance”? (cf. Luke 4:16–20 and Isa. 61:1–2). I think it is. Indeed, the very reason he felt called upon to deny he was destroying the Torah was that his message might easily have been misinterpreted that way. It could not have been misinterpreted had he taught legalistic adherence to the law.

Nowhere does Jesus recommend punishment by human individuals or groups for the sake of just retribution. Rather, in the New Testament the spirit is this: “Recompense to no man evil for evil … avenge not yourselves” (Rom. 12:17–19). How this passage can be twisted into favoring capital punishment by the state, I fail to see. We are emphatically warned against that kind of judging condemnation which vengeance and retribution require (cf. Matt. 7:1 ff.; Rom. 2:1). If we need further documentation, we should ponder deeply Jesus’ citation of the Lex Talionis, or law of retaliation, of Exodus 21:23, and his contrasting and explicit statement in Matthew 5:38–39. We are called to a righteousness which exceeds that of the legalists (Matt. 5:20). The principle of retribution is to be replaced with that of reconciliation (Matt. 5:23–24).

TWO RELEVANT EVENTS

Now the fact is that the New Testament nowhere deals with capital punishment as such, in terms of principle, so that a general conclusion is stipulated. However, we do have some instances which were related to capital crimes. The most noteworthy is John 8:1–11. The woman taken in adultery had committed a crime with reference to which the Old Testament is explicit as to punishment. She was to be stoned to death (Lev. 20:10; Deut. 22:21; 22:24). Why did they think they could put Jesus on the spot in this situation, if it was not suspected that he would disagree with the law? Their suspicion turned out to be well founded. He did not say, “Do what the law says.” We find no talk about making an example of this woman in order that others may be deterred from like behaviour. We get no discourse on the abstract rightness of the death penalty, regrettable though the specific instance may be. We have instead the words, “He that is without sin among you, let him first cast a stone at her.” Is it not interesting that those who use the Bible to commend capital punishment ignore this one specific case where Jesus spoke on its applicability?

Another incident in the New Testament relates to our subject. When Paul learned that the slave Onesimus was to be sent back to his owner, Paul went to some trouble to prevent an execution. The letter to Philemon deals directly with this. Paul also included in the letter to Colossae a passage urging them to use their influence in the situation at Laodicea, which was a short distance from Colossae and the place where Philemon and his brethren lived (Col. 4:9; 4:15–17). The point was that as an escaped slave, Onesimus was, under Roman law, subject to punishment by the owner, including, at the owner’s discretion, death. Did Paul take this as a marvelous opportunity to discourse on the justice of capital punishment, and that we Christians ought not to make too much of physical life? No, Paul urged that the owner receive the slave, now an ex-convict, as if he were Paul, and that Paul himself would pay whatever punishment the owner determines, followed by the legal phrase to make it binding and official, “I Paul write it with mine own hand” (Philem. 17–18). It is pointless to argue that Paul should have agitated for revision of the civil law. Since he was in prison at the time, he was hardly in a position to do that, and under Roman government he could not have done it under any circumstances.

These examples do not provide a sufficient basis for unlimited generalization about the New Testament and capital punishment, but I certainly think they ought to cause those who claim to base justification of capital punishment on the New Testament to pause and think.

There is much I would like to add and there are many further objections to be raised against Dr. Vellenga’s article. I must, however, mention such statements as “there is no forgiveness for anyone who is unforgiving,” and the use of the Beatitude on mercy in connection with that. The passages cited (including Psa. 18:25–26) refer to God. Are we to conclude that for our part we are therefore to be merciful and forgiving only toward those who are themselves merciful and deserving? I would certainly think not. Dr. Vellenga also cites numerous passages which command respect for government and civil order. But what bearing do these have on whether we urge and work for revision of a law? This is precisely the kind of respect for due procedure and citizenship that democracy is predicated on and by which it is strengthened. These very passages have been used on occasion to justify some remarkably evil governments, but this is the first time I have found them used for what I take to be an argument that responsible agitation for revision of a law in a democracy is resisting “what God has appointed.” If that is not the burden of his argument at this point, I do not see any relevance of it whatever to the subject. And then there is his closing remark about “one generation’s thinking.” Does he not know that Victor Hugo wrote a book on this subject in 1829, that Michigan abolished capital punishment in 1847, and Rhode Island did so in 1852?

I must object most emphatically to the reference he makes to the Crucifixion. Just how this recommends capital punishment to us escapes me. And just how putting a man to death stands “as a silent but powerful witness to the sacredness of God-given life” is mystifying in the extreme.

I am well aware that what I have written here does not add up to the conclusion that capital punishment should be abolished. I do not see how one can come to a conclusion, pro or con, apart from a study of the facts. The problem then is to manifest that mind which was in Christ with reference to this issue. Those who would use the New Testament legalistically will not find any abstract law which specifically mentions the death penalty. I do maintain that what we have in the New Testament clearly places the burden of proof on those who would now retain the death penalty. No amount of charging, be it “popular, naturalistic … sociology and penology,” will substitute for the responsibility of inquiring into the facts of this subject.

3. Gordon H. Clark

In the October 12, 1959, issue of CHRISTIANITY TODAY, Dr. Jacob Vellenga had an article defending capital punishment. In the present issue Dr. Yoder and Dr. Milligan have articles opposing it. Dr. Milligan states the question in very acceptable terms: “Is capital punishment just and right?” Since Dr. Yoder asserts, “capital punishment is one of those infringements on the divine Will which takes place in society,” the wording of the question may be sharpened this way: “Is capital punishment ever right?” Dr. Yoder seems to believe that it was wrong even in the Old Testament.

Fortunately this form of the question rules out discussions on the cost of judicial procedure, the number of states that have abolished capital punishment, the (poorly-founded) doubt that execution deters murder, and other extraneous details. The question is not whether murderers escape their penalty, but whether they should. The question is not the direction in which modern penology is going, but whether it is going in the wrong direction. The question is not the efficiency of American justice. We admit that American justice leaves much to be desired. Criminals receive too much favor and sympathy. But all such details would lead to an interminable discussion. The question is simply, Is capital punishment ever justified?

THE OLD COVENANT

Both of the opposing articles rightly center their attention on the relation of the Old Testament to the New Testament. Dr. Yoder asks whether a proper Christian understanding of any problem begins with Moses, or whether a proper approach to the Bible begins with Christ himself. To minimize the Old Testament Dr. Yoder and Dr. Milligan then press the details of stoning an adulterer, of executing an idolator, of establishing cities of refuge, of appointing a kinsman of the murdered man as the executioner, and so on.

Now, in the first place, I should like to maintain that a proper understanding of the Bible begins with Moses—not with the Mosaic law as such, but with the first chapter of Genesis. In particular, when the Old Testament lays down basic principles, such as the sovereignty of God, the creation of all things, God’s control over history, the inclusion of infants in the Covenant, or other matters not explicitly abrogated or modified in the New Testament, the silence of the latter, or the paucity of its references, is not to be made an excuse for abandoning the principles of the former. As Dr. Yoder admits, there is much more information on civil government in the Old than in the New Testament. Therefore I would conclude that the Old Testament should not be minimized.

Probably every view of the controversial question of the relation between the Testaments acknowledges that the New in some respects modifies the Old. The most obvious of these modifications is the fulfillment of the ritual by the death of Christ. The Mosaic administration was superimposed upon the Abrahamic covenant 430 years afterward and was to remain in effect only until the Messiah came. Even the animal sacrifices that had been instituted before the time of Moses were types or pictorial anticipations of the one sacrifice that in truth satisfied divine justice. To offer them now would be to imply that Christ had not yet come. Because of this, Dr. Milligan’s argument that the defense of capital punishment consistently requires animal sacrifice is invalid. What else could Hebrews chapter 9 possibly mean?

For this reason too, Dr. Vellenga’s reference to the Crucifixion as a point in favor of capital punishment is not so irrelevant as the opposition alleges, for the death penalty was not merely Pilate’s decision to be regarded as mistaken; rather it was God who had foreordained that without the shedding of blood there is no remission of sin.

Next, if the cessation of the ritual is the most widely understood modification of the Old Testament, the increase of biblical ignorance since the seventeenth century seems to have erased from memory the point that the civil laws of Israel also are no longer meant to apply. God abolished the theocracy. Such is the teaching of Jesus in Matthew 21:33–45. The Pharisees thought that any men who would kill the Messiah would be miserably destroyed, but that God would then let out the vineyard to other High Priests and that the theocracy would continue as before. Jesus said no. The Kingdom would be taken from the Jews, the theocracy would be ended, and a new order would be instituted in which the rejected stone would become the head of the corner. So it has happened. There is no longer any chosen nation. Therefore the detailed civil and criminal code of Israel is no longer binding.

For this reason we do not have cities of refuge: police and judicial protection is sufficient. We are not required to marry our brother’s widow, because the purpose of preserving his name and tribe is no longer in effect.

CRIME AND PUNISHMENT

This does not, however, and in logic cannot imply that capital punishment is wrong. Would one argue that since the Jews were forbidden to lend money on interest to other Jews, it is now wrong to obey that law and to refuse to accept interest from other Christians? This is just bad logic. At most, the rejection of the civil law as a whole would merely leave the individual details as open questions. And even one who strongly deprecates the Old Testament must in honesty admit that several of those details could be wisely adopted today. In the present depraved condition of the United States, we might even wisely execute adulterers and pornographers.

Where the opponents of capital punishment go astray is in the assumption that approval of execution depends on its inclusion in the national laws of Israel. Its inclusion there is of course quite sufficient to show the falsity of Dr. Yoder’s assertion that execution is an infringement on the divine Will. It was God who ordered capital punishment. Therefore it is entirely incorrect to say that capital punishment is an infringement of divine prerogatives; and the question, Is capital punishment ever right? must be answered in the affirmative.

Of course, this much does not satisfy Dr. Milligan. The pertinent question is, Is capital punishment ever right today?

To this question it should be replied that although the ritual and civil laws are no longer in effect, the moral law is. I cannot agree with Dr. Milligan that in the New Testament “we move to a different base for law.” The basis of moral law in all ages is the preceptive will of God. The laws against adultery and murder are not merely Mosaic enactments: they go back to creation. More to the point, capital punishment is commanded by God in his revelation to Noah, and by implication at least was applicable to Cain (Gen. 4:10, 14).

A GENERAL RULE

God’s dealing with Cain, however, indicates that it is not absolutely necessary to execute every murderer. When we say that God commanded capital punishment, the meaning is that this penalty was established as the general rule. It does not mean that there could not rightly be exceptions. Remember, the question is, Is capital punishment ever right? Therefore, the case of the woman taken in adultery has no bearing on the matter. For one thing, it should be noted that the woman was taken in the very act; but the scribes and Pharisees had arrested only the woman and not the man, whom they must also have found in the very act. Aside from Jesus’ intention to reveal the hypocrisy of the religious leaders, there may have been other reasons for not inflicting the penalty on this woman. But can this one case support a theory of civil law while all the rest of the Bible is ignored? If this were so, there would be no penalties of any sort for any crimes.

It is this point that the other two authors do not discuss. Dr. Yoder, in his second paragraph, does not want to lower the standards of justice, excuse crime, or gloss over the wrongness of wrong. But he supplies no reason for inflicting prison terms instead of execution. In fact, his argument against personal responsibility, its seemingly Freudian psychology, its placing the blame on society as a whole, would rather suggest that no penalties for any crime should be inflicted. Until the opponents of capital punishment formulate their theory of civil authority, nothing more need be said on this point.

To indicate that the many details in the two articles have not been ignored, even though passed over in silence here, I shall make mention of Jesus’ reading the scroll in the synagogue in Nazareth. Jesus stopped reading just before the clause on the day of vengeance. Dr. Milligan thinks that this is significant. No doubt it is. But it is not significant of the fact that the state should not execute criminals. It is significant of the fact that the ministry of Jesus at that time was to proclaim the year of Jehovah’s favor. The day of vengeance is to come later when Jesus shall be revealed from heaven in flaming fire, rendering vengeance to them that know not God. Such passages have nothing to do with civil government, and to press them against capital punishment is inadmissible.

Now, finally, it is our contention that the New Testament authorizes capital punishment and war as well as the Old. Dr. Milligan does not mention the power of the sword granted to earthly governments in Romans chapter 13. Dr. Yoder tries to make this power merely a symbol of judicial authority without any reference to execution. Is not this a measure of desperation? What are swords used for? Is taxation, mentioned in the same passage, also a symbol of civil authority without any reference to extracting money from the pockets of the people? No, such an interpretation completely gives away the weakness of the case for symbolism.

In other words, the opponents of capital punishment offer no theory of civil government, they seriously misinterpret the Bible, and they are in conflict with the principles of Christian ethics.