TEXT: Matthew 25:31–46

The space age has generated its own questions. One asked recently was, “What would astronauts do with the body of a crew member who died on a long voyage to a distant planet?” A scientist replied, “The body could be pushed out into empty space where it would dissolve into cosmic nothingness.” The prospect, while frightening, is obviously true. Yet even in this materialistic age, we remember the long Hebrew, Greek, and Christian traditions with the joyful hope that while the body may dissolve to “cosmic nothingness,” life continues.

We listen to Isaiah as he writes: “Awake and sing, ye that dwell in dust: for … the earth shall cast out the dead” (Isa. 26:19b). We view death with “the Preacher” and hear: “Then shall the dust return to the earth as it was: and the spirit shall return unto God who gave it” (Eccles. 12:7). We peer over the rim of eternity with Daniel and are stirred by his words: “Many of them that sleep in the dust of the earth shall awake, some to everlasting life, and some to shame and everlasting contempt” (Dan. 12:2).

When we turn to the pages of the New Testament, the words of Jesus lift our hopes to the stars: “I am the resurrection, and the life: he that believeth in me, though he were dead, yet shall he live.” “My sheep hear my voice … and I give unto them eternal life.” “In my Father’s house are many rooms.” He proved his words with his resurrection in triumph over the grave, and now, hope becomes assurance.

We turn the worn pages of an old philosophy book and hear the most venerable Greek philosopher, Socrates, say on the eve of his execution, “… when I have drunk the poison I shall leave you and go to the joys of the blessed.… Be of good cheer, then, my dear Crito, and say that you are burying my body only …” (B. Jowett, trans., The Works of Plato, New York: Tudor Publishing Co., III, 267, 268). Thus even a pagan writing four centuries before Christ encourages us to hope for more than “cosmic nothingness.”

Actually, for most men the question is not whether or not there is a life after death, but, What kind of life is there for men who seriously consider the future? How can a worthwhile future life be achieved? Jesus Christ, the only one who ever came back from the grave to prove his promises, clearly teaches that it is God’s gift given through himself. We hear him say again concerning his followers, “I give unto them eternal life.” The whole Protestant Reformation was a return to the simple teaching of Jesus and the New Testament doctrine that eternal life, salvation, is the gift of God, not the achievement of men. Furthermore, Christ, as well as the writers of Scripture, made it very plain that eternal life is conditional, that it must be accepted to be enjoyed.

Strangely enough, this need for commitment and decision to enjoy God’s gift of eternal life has often been denied, especially in America. From the time of the theologian Origen at the beginning of the third Christian century, some Christians have believed that God will ultimately save all men. Their viewpoint, called “universalism,” has many historic sources. However, in America it has until recently been almost home-grown rather than part of a long-standing minority tradition.

It was often the sincere response to a lurid presentation of the judgment of God in physical terms. Jonathan Edwards’s sermon on “Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God” was the best of this venerable tradition of preaching the judgment of God in such a way that it appeared that God delighted in the tortures of the damned. How memorable are his words:

The God that holds you over the pit of hell much as one holds a spider or some loathsome insect over the fire abhors you, and is dreadfully provoked. His wrath toward you burns like fire; he is of purer eyes than to bear you in his sight; you are ten thousand times as abominable in his eyes as the most hateful and venomous serpent is in ours [Mayo W. Hazeltine, ed., Orations, New York: Collier Publishing Co., V, 1811].

He had many crude imitators, some of whom still ply their trade. Men of good will immediately saw that this treatment of the judgment of God neither squared with the character of God presented by Jesus Christ in the New Testament, nor faced the truth that hell was prepared for spiritual beings, the devil and his angels. The reaction was complete, and “Universalists” denied that God judged anyone after this life.

Second, there is a sentimental “universalism” that has no establishment but many prophets and voices. Its source is in the native sentimentality of American Protestants, and its theology is that God is too loving to punish anyone. Even a liberal mind like that of Harry Emerson Fosdick revolted at theology based on such sloppy thinking, held together by the glue of sentiment. He declared that God judged the unrepentant out of love for all men rather than because of a defect in his own nature.

Theology Based On Emotion

The third source of our home-grown American universalism is a psychological one. It does not take an acute observer to discover that many preachers who preach hell-fire and damnation are motivated more by the needs of their own twisted personalities than by a simple desire to declare the whole word of God. This simple observation has often been extended to a universal principle. Recently I was discussing this subject with a well-known leader who finally asked me, “Why do you need a hell?” My answer was, “I don’t need one. However, Jesus Christ said that there is one. If we can’t believe that we have a true account of his teachings on this subject, how we can believe any other part of his recorded teachings?” Further reflection led me to see why this particular man needed that there not be a hell. For the concept of hell is rejected by some men because they clearly see that in proclaiming it some preachers are moved more by their own vindictive feelings than by the Word of God. Yet others reject the concept of hell because of a different emotional need. Rut emotion is a poor basis for a theology. Evangelical Christianity has been able to deal effectively with these viewpoints.

However, a new universalism now poses a threat to the clear-cut scriptural teaching. It is doubly dangerous because its source is in the teachings of the most distinguished ally of evangelical Christianity, Karl Barth. This world-famous Christian theologian has turned many leaders of thought from philosophical theology back to a biblical theology. His monumental treatises have done much to move the whole Protestant church away from its drift into scientific naturalism, the “modernism” of a former generation.

The situation has been made more complex because many Christian churches have been greatly influenced by his thought. The Gospel is simple, but it must be applied to a very complicated world. Few men have the ability or even the time to work out for themselves the application of the Gospel to their own generation. Most ministers and theologians depend upon the few geniuses of their age for the framework of their theology and the application of the Gospel to their day.

Applying The Gospel To The Age

There are three basic approaches which great thinkers have always used in defending and in interpreting the Gospel as well as in applying it. The first is that of capitulating to the thought-forms of their generation while trying to retain what they call the essential core of the Gospel. Rudolph Bultmann has been the foremost exponent of this method. The second is that of dialogue or conversation in which the theologian effects a synthesis of the most valid concepts of the age and of the eternal Gospel. Paul Tillich is the leader of this approach. Unfortunately he often sounds more like a humanist than a Christian theologian informed by biblical sources. The last approach is the biblical one. The theologian using this method judges the world and his age by biblical thought-forms. While he understands and appreciates the thought-forms of his age, he is not bound by them; rather, he brings them under the judgment of the Word of God. Karl Barth is the ablest and best-known leader of this method. It is because he has succeeded so well that many great gains in evangelical theology have been made in the last generation, and these strides are tributes to this great leader.

But two emphases of Karl Barth have opened the door to a new universalism: his emphatic declaration of the triumph of the sovereignty and the grace of God. His thesis is that in Christ, God chose death and rejection for himself and life and acceptance for mankind. He clearly teaches that the grace and the sovereignty of God cannot be thwarted by man but will triumph. At the same time, he tries to avoid the implications of this by saying that only human presumption leads us to say what God’s final disposition of man in eternity will be. However, it is apparent that if God cannot be resisted because he is sovereign and that if in Christ he has chosen life and acceptance for all men, then all men will be saved. This is simply the old universalism of Origen, clothed in twentieth-century dress. It transcends our own native universalism and is therefore acceptable to those who have long defended Christian theology against its onslaughts.

The new universalism is enormously attractive even to evangelicals. First, it is born and nurtured within the basic evangelical tradition of biblical theology and doctrine. Second, it gives a solution to the problem of sin that does not lessen the seriousness of sin while accepting a substitutionary view of the Atonement of Christ. Third, it gives hope, based upon the work of Jesus Christ rather than upon human sentiment or the silence of the Scriptures, for the three classic types of lost men. It gives hope for the salvation of those who have never heard the Gospel. It gives hope for another chance of salvation for those who in their lifetime heard only a garbled version of the Gospel. It also provides the blight hope of a second opportunity for those who have heard the Gospel but have rejected it. The last two enticing features of this viewpoint mean much to people who have lost unrepentant loved ones. Thus a speculative theology becomes an applied one.

Because the new universalism has an evangelical flavor, because it is rooted in biblical concepts, and because it is so attractive, its threat to the whole evangelical cause is increased. Its many dangers are common to all types of universalism.

The first danger is the implicit denial of man’s freedom to choose or to reject a relation with God. Once men believe that God coerces or manipulates man, the majority political or religious group feels free to use coercion and manipulation to gain compliance. Institutions and men have been known to confuse themselves with the Almighty, and so the views that they hold of God affect their relations to men.

The second danger to evangelical Christianity is in the area of authority. In the name of biblical concepts of sovereignty and grace, the explicit, particular teachings of Jesus Christ concerning salvation, grace, and the eternal judgment of the lost are rejected. To deny the validity of the statements attributed to Jesus Christ in the Gospels concerning sin and the judgment of the unrepentant is to reject either the authority of Christ or the accuracy of those who reported his teachings.

The third threat of the new universalism is that which it poses to the outsider. While few men today ever decide for Christ out of fear of eternal retribution, there is a sense of urgency to a choice that must be made now if eternal life is to be enjoyed. To assure all men that they are now redeemed is to remove any urgency in choosing for Christ. And this is the inevitable outcome of the doctrine. Listen to the words of a leader in evangelism from one Protestant denomination:

Do you have good news for all men, for the exploited and the unjust, for the saint and the sinner, for the religious and the irreligious, for the post-Christian man of unbelief? Or is it good news only to those who obey, only to those who decide, only to those who worship, so that your gospel is restricted in its goodness, confining within its breadth a new law rather than a new gospel, a religion of man’s works rather than God’s gracious workmanship?

The fourth major area of the life and work of Christians which is affected by the new universalism is that of evangelism. Universalism re-directs denominational programming from a search for the lost to a futile attempt to modify the social structure of society apart from individual conversions within that structure. Hear again the words of the above-mentioned leader:

Traditionally we have aimed at the response of individual men and women in faith and obedience to say yes to Jesus Christ and to join the church. But the call of evangelism is a response and a decision by a society in the world, a University of Mississippi, a U.S. Steel Corporation, the American Medical Association, a Theological Seminary in terms of their corporate life and “social ethics,” the way in which they function as a corporate power structure of inter-related people in relation to the rest of society.

Once all men are viewed as redeemed regardless of their decision on the subject, there is little left for the evangelist to do but to initiate social action. Ironically enough, if the new universalism is translated into a program long enough, the churches will be empty of people who should modify the structures of society out of love for Christ and for people.

Loss Of A Sense Of Urgency

Pastors and lay members of local churches will inevitably lose their sense of personal responsibility for the lost, if they accept the new universalism. With the loss of responsibility will also come a loss of urgency in reaching those who have never made a personal decision. In a rapidly moving society such as ours, many churches will be out of business within less than a decade if a sense of urgency is lost. If the new universalism becomes widespread in the historic Protestant churches in which it is finding its greatest welcome, the chief religious forces in American society will soon be the radical sects and Roman Catholicism. It will be interesting to see what will happen in the top ranks of denominational leadership when, as dwindling membership of local churches is expressed in the offering plate, the new universalism inevitably results in reduced denominational budgets.

Most men of good will are human enough to wish that there were no hell and no eternal judgment. Yet the teaching of Jesus Christ on both the eternity and the certainty of divine judgment for the unrepentant is just as clear as his teaching on the eternity and the certainty of the Beatitudes. In all of the known universe there is not one shred of eternal hope for man apart from repentance from sin and faith in Jesus Christ as the only Saviour sent by God. The tragedy is that so many of us who believe in the realities of eternal judgment fail to see or act upon our personal responsibility for the lost.

I heard Dr. Martin Niemöller of Germany tell how God had to give him a vision in a dream to make him aware of his personal responsibility for witnessing to others. He stated that he had felt no obligation to witness to his Nazi guards until he had the dream, during the seventh year of his eight-year imprisonment for defying Hitler. In his dream he saw Hitler pleading his case before the judgment bar of God. His excuse for his sins was that he had never heard the Gospel. Then Dr. Niemöller heard the voice of God directed toward himself: “Were you with him a whole hour without telling him of the Gospel?” Awakening, he remembered that he had been alone with Hitler for a whole hour without witnessing to him. Then he saw clearly that it was his duty to witness to all men, even his despised guards.

Must it take a vision from God to make us see that the eternal destiny of others is our responsibility? There is a God-given urgency to our witness. The Gospel of Jesus Christ is the only sure message of hope that can turn men away from the despair of a fate of “cosmic nothingness.”

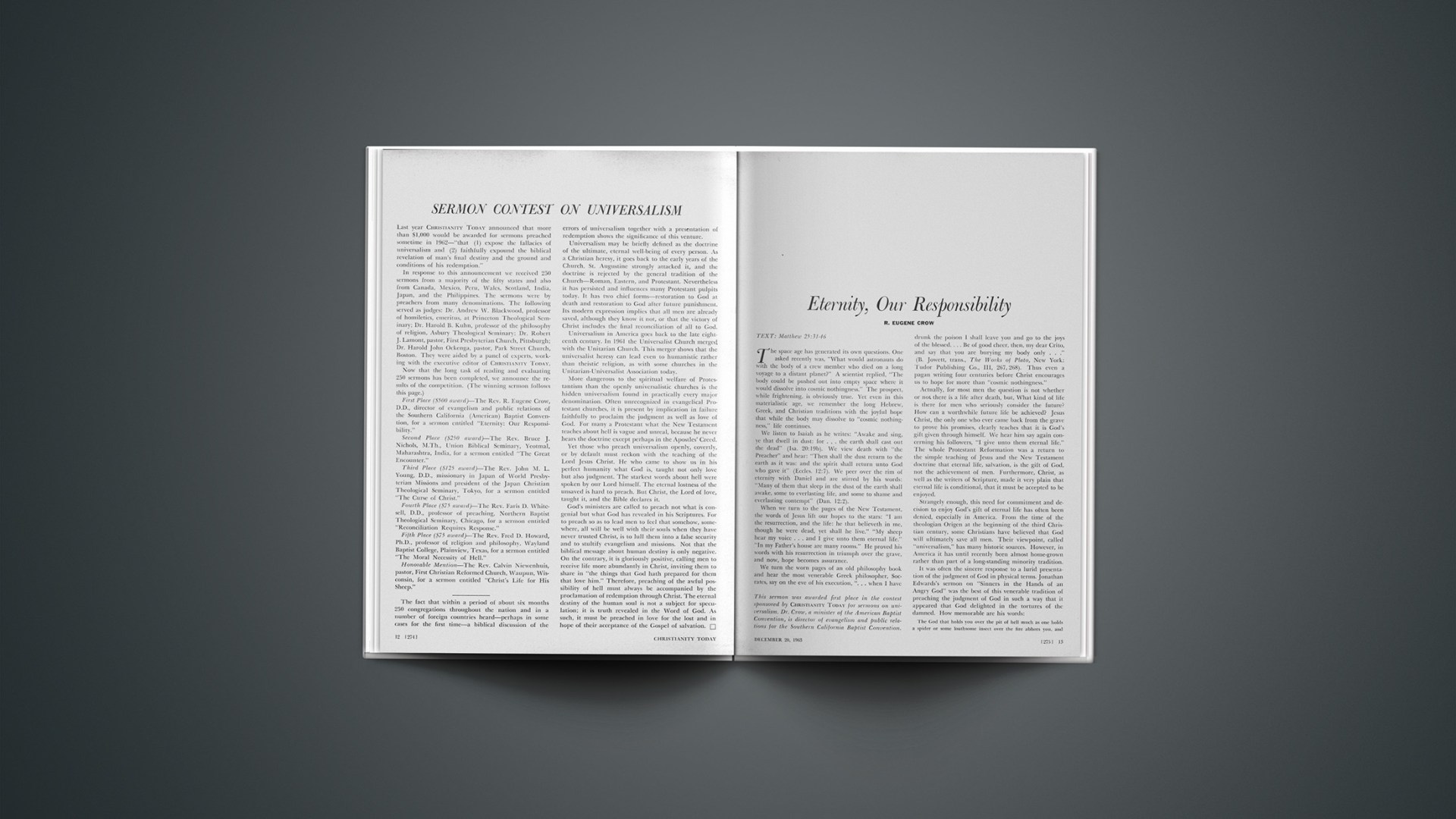

This sermon was awarded first place in the contest sponsored byChristianity Todayfor sermons on universalism. Dr. Crow, a minister of the American Baptist Convention, is director of evangelism and public relations for the Southern California Baptist Convention.