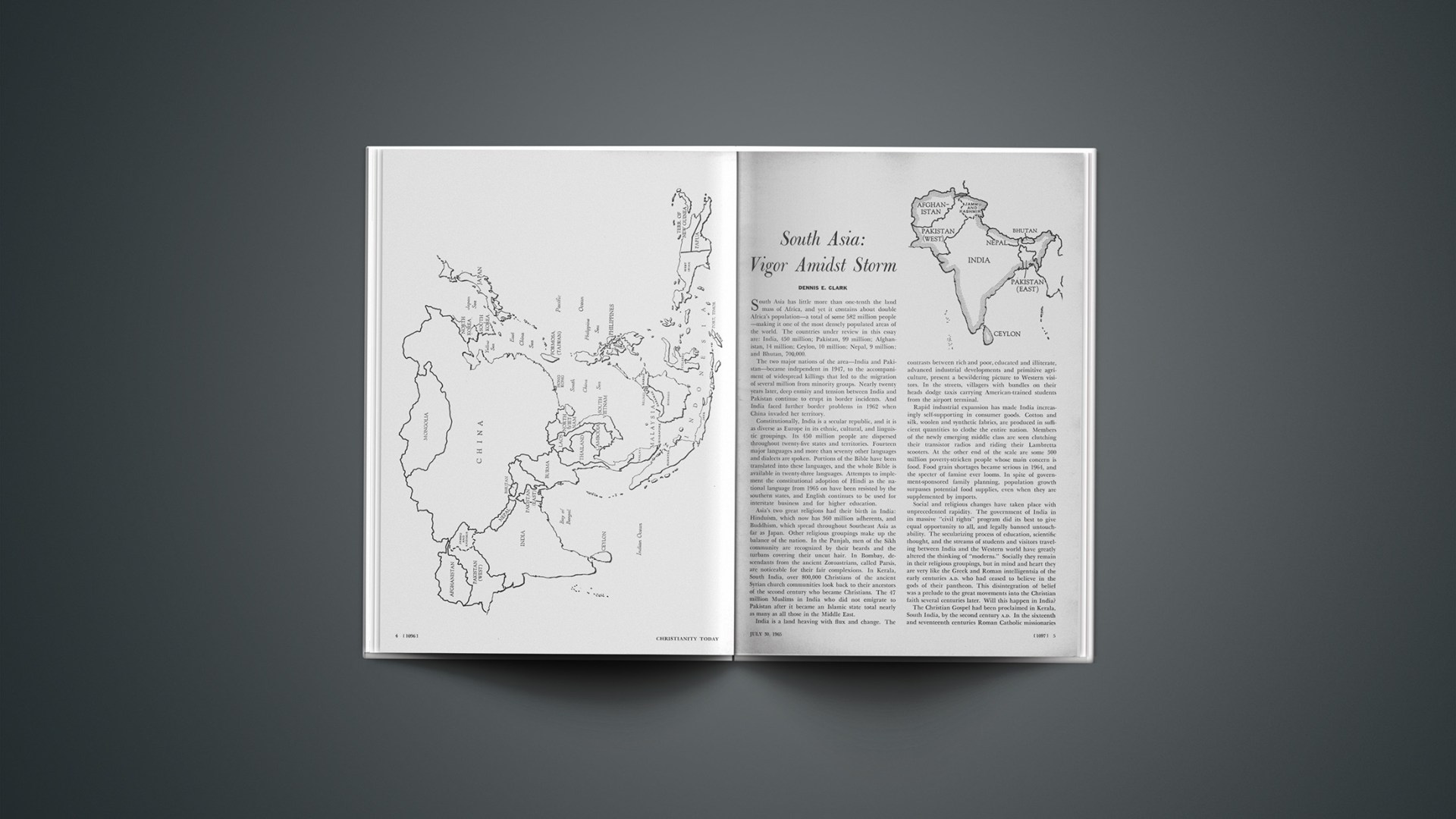

South Asia has little more than one-tenth the land mass of Africa, and yet it contains about double Africa’s population—a total of some 582 million people—making it one of the most densely populated areas of the world. The countries under review in this essay are: India, 450 million; Pakistan, 99 million; Afghanistan, 14 million; Ceylon, 10 million; Nepal, 9 million; and Bhutan, 700,000.

The two major nations of the area—India and Pakistan—became independent in 1947, to the accompaniment of widespread killings that led to the migration of several million from minority groups. Nearly twenty years later, deep enmity and tension between India and Pakistan continue to erupt in border incidents. And India faced further border problems in 1962 when China invaded her territory.

Constitutionally, India is a secular republic, and it is as diverse as Europe in its ethnic, cultural, and linguistic groupings. Its 450 million people are dispersed throughout twenty-five states and territories. Fourteen major languages and more than seventy other languages and dialects are spoken. Portions of the Bible have been translated into these languages, and the whole Bible is available in twenty-three languages. Attempts to implement the constitutional adoption of Hindi as the national language from 1965 on have been resisted by the southern states, and English continues to be used for interstate business and for higher education.

Asia’s two great religions had their birth in India: Hinduism, which now has 360 million adherents, and Buddhism, which spread throughout Southeast Asia as far as Japan. Other religious groupings make up the balance of the nation. In the Punjab, men of the Sikh community are recognized by their beards and the turbans covering their uncut hair. In Bombay, descendants from the ancient Zoroastrians, called Parsis, are noticeable for their fair complexions. In Kerala, South India, over 800,000 Christians of the ancient Syrian church communities look back to their ancestors of the second century who became Christians. The 47 million Muslims in India who did not emigrate to Pakistan after it became an Islamic state total nearly as many as all those in the Middle East.

India is a land heaving with flux and change. The contrasts between rich and poor, educated and illiterate, advanced industrial developments and primitive agriculture, present a bewildering picture to Western visitors. In the streets, villagers with bundles on their heads dodge taxis carrying American-trained students from the airport terminal.

Rapid industrial expansion has made India increasingly self-supporting in consumer goods. Cotton and silk, woolen and synthetic fabrics, are produced in sufficient quantities to clothe the entire nation. Members of the newly emerging middle class are seen clutching their transistor radios and riding their Lambretta scooters. At the other end of the scale are some 300 million poverty-stricken people whose main concern is food. Food grain shortages became serious in 1964, and the specter of famine ever looms. In spite of government-sponsored family planning, population growth surpasses potential food supplies, even when they are supplemented by imports.

Social and religious changes have taken place with unprecedented rapidity. The government of India in its massive “civil rights” program did its best to give equal opportunity to all, and legally banned untouchability. The secularizing process of education, scientific thought, and the streams of students and visitors traveling between India and the Western world have greatly altered the thinking of “moderns.” Socially they remain in their religious groupings, but in mind and heart they are very like the Greek and Roman intelligentsia of the early centuries A.D. who had ceased to believe in the gods of their pantheon. This disintegration of belief was a prelude to the great movements into the Christian faith several centuries later. Will this happen in India?

The Christian Gospel had been proclaimed in Kerala, South India, by the second century A.D. In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries Roman Catholic missionaries were successful in the Portuguese enclaves, and some intrepid pioneers traveled north to the court of Akbar the Great. In the nineteenth century Christianity made some of its greatest gains. In “mass movements” whole communities became Christian, particularly in the Punjab (now West Pakistan), in Bihar among the Adiavasis (now numbering some 500,000), in Assam, where whole tribes are now Christian, and in South India. According to present statistics, the Christian community numbers about 14 million; fewer than half are Roman Catholics.

Despite various gloomy forecasts, church growth continues with greater momentum than had been thought possible. One bishop of the Church of South India casually mentioned that 1,000 converts had been baptized in his diocese in 1964. Former high-caste peoples in Andhra join the Christian Church regularly. Indian Christians in all walks of life communicate the reality of Jesus Christ to their non-Christian neighbors; there is, for example, a Goan colonel who gave his Hindu major an “imitation of Christ” as they faced the Chinese in the Himalayas, or a Christian thoracic surgeon in a government hospital about whom colleagues say, “He is a dedicated man who believes in life beyond death.”

Christianity’s influence is greater than its numerical strength. Many present-day leaders have been educated in one of the several hundred Christian high schools or colleges. Christians hold responsible government and business positions. One is governor of an important state; another is chief personnel officer in the largest industrial undertaking in India. The Christian ethic has been accepted as a standard of behavior by many who would oppose the unique claims of Jesus Christ. Monogamy is now the norm, and many Hindus have come to monotheism from previous polytheistic beliefs.

The large majority of Protestants belong to the older churches. Evangelical missions, which expanded after World War II, have not yet developed a sizable church constituency. To strengthen true witnesses in existing churches is an urgent task for evangelicals.

Problems Of The Churches

The problems of most churches are spiritual and ethical rather than theological. Thus the theological conflicts of North America arc largely irrelevant in India. This also accounts for the growth of such groups as the Evangelical Fellowship of India, based on a burden for spiritual renewal and revival rather than an “anti-ecumenical” attitude.

Churches in India have their own problems. These include syncretism, which cuts the nerve of evangelism; lack of Bible teaching for the churches in rural areas as well as in new suburbs; compromise by conforming to the world for the sake of a job or economic betterment; and timidity, which avoids evangelism and witness for the sake of “peace and quiet.”

In answer to these problems, such programs as the following are receiving attention: Members of the Council of Evangelists of the Evangelical Fellowship of India are constantly engaged in evangelistic campaigns and Bible ministry throughout India; the demand is greater than the supply of personnel. The Union Biblical Seminary, Yeotmal, is training Christian leaders at the B.D. level in the foundational truths of the Christian faith. The Christian Educational Evangelical Fellowship (CEEFI) has embarked on an intensive program to provide a fully graded curriculum for Sunday schools and to train teachers in a Christian education program. In the area of mass communications, some forty Christian publishers and bookshops handle an increasing volume of evangelical literature, and radio programs are taped in all major languages and flown to the Far East Broadcasting Company in the Philippines for shortwave transmission to India.

Two neglected doors of opportunity are evangelism and pastoral work in the many new industrial cities, and the production of evangelical literature for the modern mind.

India’S Neighbors

Pakistan, with 99,000,000 people, is the world’s largest Muslim land. Many of the modernizing tendencies that are now current in South Asia are also at work in Islam, though at a slower rate, for Islam is more rigid than Hinduism or Buddhism. Pakistan’s flirtation with China may produce deeper anti-American feelings and have an effect on Christian work.

Pressures from Muslim leaders have resulted in the banning of several Christian apologetic works that had been freely circulated over the past forty years. Not long ago a shooting affair by Muslim fanatics in a Christian bookstore heightened the fear of Christians that violence may break out against them.

Numbers of Christians have recently emigrated from East Pakistan to India, not primarily because of religious persecution, however, but for agricultural reasons.

In Christian schools it is now compulsory to teach Islam as a subject to Muslims, although the Christian faith can likewise be taught to Christian students.

A general timidity characterizes the Christian community. This must be pushed aside by boldness if the Church is to avoid becoming an introverted community, more concerned for survival than expansion.

Afghanistan remains, with Saudi Arabia, one of the few Muslim countries in which no national church exists. As a result of long and patient witness by Christians in local employment, Christian institutions may soon receive official recognition.

In the last decade Nepal has seen the birth of its first churches at the price of jail sentences for some involved in their establishment. One pastor is still in jail.

Bhutan’s door is creaking open for the first time with an invitation to Christian teachers and medical personnel to enter in a professional capacity.

In Ceylon, where the religious situation resembles that in India, recent changes in government will give greater liberty to the Christian churches.

The work of Jesus Christ in the vast area of South Asia can be summarized in the words of Kenneth S. Latourette, “Vigor amidst storm.” The greatest opportunities for church expansion still lie before us.

T. Leo Brannon is pastor of the First Methodist Church of Samson, Alabama. He received the B.S. degree from Troy State College and the B.D. from Emory University.