Christianity was born in Asia Minor. The first missionaries were Asians. The early centuries of Christian history reveal churches in South India and as far east as China, where Nestorian missionaries had gone. But for the most part Asia has come into contact with the Gospel only since the eighteenth century and the rise of the modern missionary movement.

Today the lands of Asia from Pakistan to Japan contain more than half the world’s population. In this area are found most of the world’s living religions, all major races, and tremendous cultural and linguistic diversity. In the twenty years following World War II, a dozen countries of South and East Asia gained political independence. Throughout the area colonialism, apart from Communist neo-colonialism, has practically come to an end. In the next twenty years, according to demographers, at the present rate of growth the countries of South and East Asia alone will have more people than there are in the entire world today.

In this vast area where each country presents its own problems and opportunities for evangelism, generalities are extremely difficult to make. Analytical studies of church growth across Asia are needed but are notably lacking at the present time. Nevertheless, some things stand out in assessing the impact of the Gospel in Asia.

The Church: A Minority Community

Except for the Philippines, where Roman Catholics constitute 57 per cent of the population, the Christian community is a small minority in most Asian countries. Across Southeast Asia as a whole, Christians of all descriptions number only three in a hundred.

If the churches that are in Asia are to increase in number and influence beyond the present rate of population growth, certain aspects of missions merit attention. In most Asian countries, with the exception of the Philippines, the Protestant churches do not represent a fair cross section of the total populace. Japanese Christians largely come from the urban middle class and the well-educated. In predominantly Buddhist Burma, the response has been largely from non-Buddhist tribal peoples. In India and Pakistan 80–90 per cent of the Christians have come from socially and economically depressed classes. A church largely confined to one social or geographical segment of the population is not an effective bridge for reaching the entire nation. All Asian countries have frontiers—cultural and religious, as well as geographical—that need to be infiltrated by a witnessing community of believers.

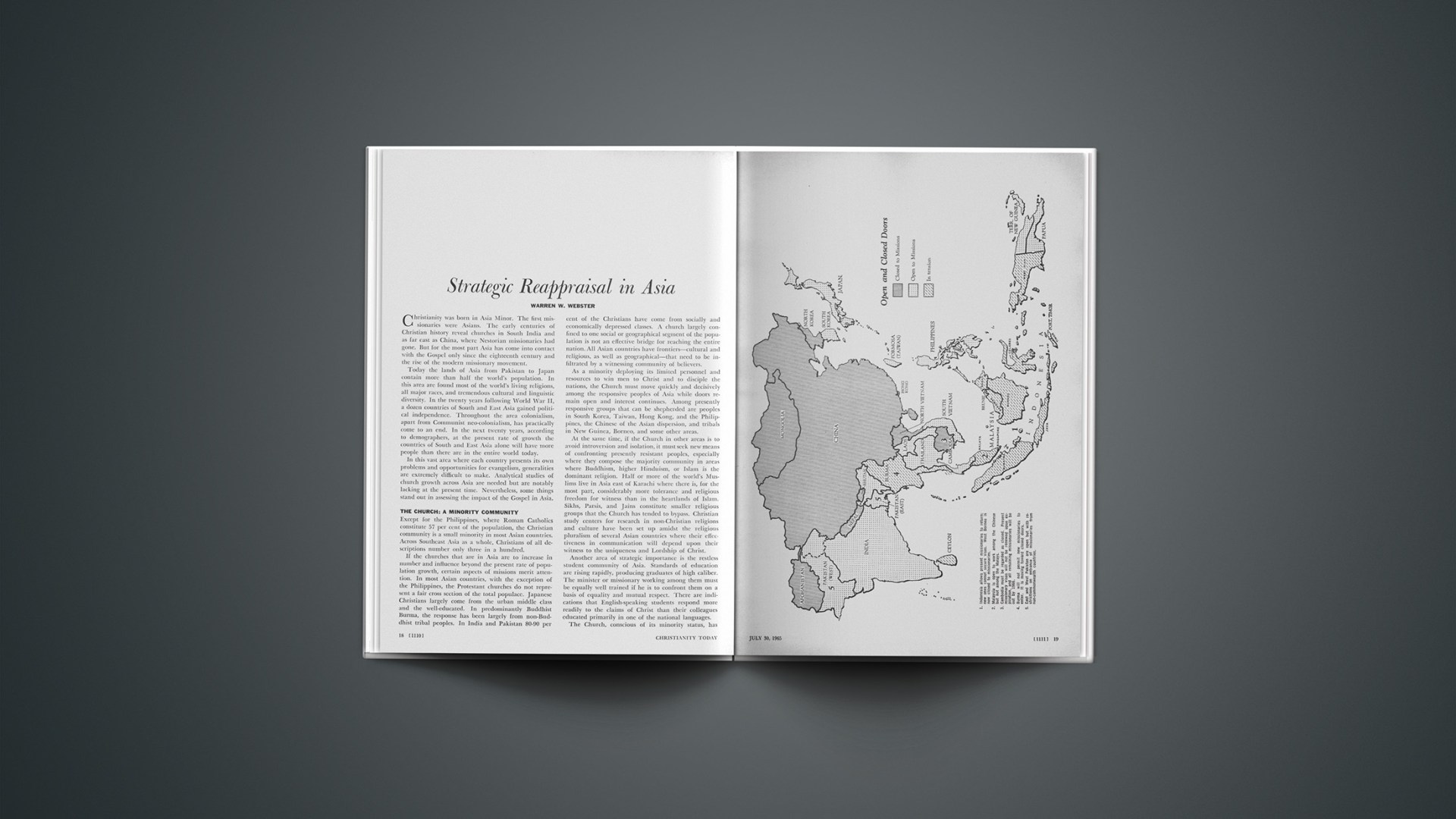

As a minority deploying its limited personnel and resources to win men to Christ and to disciple the nations, the Church must move quickly and decisively among the responsive peoples of Asia while doors remain open and interest continues. Among presently responsive groups that can be shepherded are peoples in South Korea, Taiwan, Hong Kong, and the Philippines, the Chinese of the Asian dispersion, and tribals in New Guinea, Borneo, and some other areas.

At the same time, if the Church in other areas is to avoid introversion and isolation, it must seek new means of confronting presently resistant peoples, especially where they compose the majority community in areas where Buddhism, higher Hinduism, or Islam is the dominant religion. Half or more of the world’s Muslims live in Asia east of Karachi where there is, for the most part, considerably more tolerance and religious freedom for witness than in the heartlands of Islam. Sikhs, Parsis, and Jains constitute smaller religious groups that the Church has tended to bypass. Christian study centers for research in non-Christian religions and culture have been set up amidst the religious pluralism of several Asian countries where their effectiveness in communication will depend upon their witness to the uniqueness and Lordship of Christ.

Another area of strategic importance is the restless student community of Asia. Standards of education are rising rapidly, producing graduates of high caliber. The minister or missionary working among them must be equally well trained if he is to confront them on a basis of equality and mutual respect. There are indications that English-speaking students respond more readily to the claims of Christ than their colleagues educated primarily in one of the national languages.

The Church, conscious of its minority status, has attempted to find shortcuts to mass evangelization through the use of such means as literature, radio, television, and audiovisual aids. These continue to play their part, though with considerable limitations in Asia.

Literature outreach is limited by the fact that two-thirds of the adult population of Asia cannot read a Gospel or tract in any language. Literacy programs undertaken by government and private bodies, including church and mission organizations, have produced varied results. In the decade from 1951 to 1961, Indonesia, the Philippines, Cambodia, and the Republic of Viet Nam effected substantial reductions in illiteracy. In India and Pakistan, on the other hand, while the proportion of illiterate adults declined slightly (to 76 per cent and 81 per cent, respectively), the total number of illiterates either remained stationary or rose because of the rapid population growth that characterizes most countries with high illiteracy. In such situations the Church will continue to find literacy work valuable—both directly and indirectly—as a means of evangelism. It has proven particularly successful in “re-evangelizing” second- and third-generation Christians whose faith was never very deeply rooted so long as they could not read the Bible for themselves.

Although radio appears to reach everywhere, in actuality its effectiveness is related to the number and location of receivers. A recent UNESCO report stated: “Although radio is called a means of mass communication, in most Southeast Asian countries there is as yet no established communication with the actual masses.” Outside of Japan and the more developed areas of Asia the radio is still a luxury. Some countries with government-controlled radio allow no regular Christian broadcasts. Elsewhere Christian radio stations are too often limited in number, programming, or outreach. Nevertheless, as long as freedom for operation remains, Christian broadcasting is likely to play an increasing role as an auxiliary means of evangelism.

Of supreme importance to the minority church in Asia is the thorough training of its members in Christian doctrine and practical Christianity, in effective witness under any political conditions, in an awareness of Communist objectives and methods, and in the possibility of successfully maintaining a Christian testimony should church and mission institutions be taken over by the state. In every place, nuclei of believers should be prepared who are willing to enter into a deep fellowship with Jesus Christ—men and women who are ready to suffer for Christ and remain true to him whatever changes may take place in the years to come. They may function now as prayer cells for the evangelization of Asia while setting an example by disciplining themselves in regular patterns of personal evangelism and acknowledging in all things the primacy and sovereignty of the Holy Spirit in the work of missions. Even a few with God can be a creative and redemptive minority!

The Church: Rooted In The Soil

Despite all that has been said about indigeneity, church life and institutions are too largely alien transplants from the West. In many places Christianity still “looks” Western. While the Church as a supra-national and supra-cultural fellowship must be free to share elements of organization, liturgy, music, art, and architecture across national lines, it is not desirable for such borrowing to move in only one direction. A fresh appraisal needs to be made of both message and methods in Asia, so that what is purely Western can be discarded and what is essentially and eternally from the mind of God retained. Basic Christianity can withstand any type of government pressure; a Westernized form of it may not.

Self-support for the Asian churches cannot be overemphasized. As long as they depend upon foreign funds for their basic life and ministry, they will be looked upon as foreign institutions. In view of the oneness and interdependence of the Body of Christ and the precedent of the New Testament, it cannot be wrong for churches in one geographic area to assist those in another; but it may be inexpedient. In Asia today it seems undesirable for any church to depend on foreign funds for the support of its ministry and regular congregational program. Outside aid limited to emergencies or to joint projects in evangelism, education, and service is not necessarily damaging to the self-respect of congregations that have first learned to assume their own local responsibilities.

The Church: A Lay Movement

The churches in Asia, with few exceptions, have been slower to rediscover the ministry of the laity than those in South America. Asian churches have tended to follow the West in professionalizing the evangelistic and missionary function and then wonder why it is so hard to get the “non-professional” member enthusiastic about evangelism. Japan has small Christian congregations, many averaging only twenty-five to forty members; yet the feeling predominates that to have a “church” there must be a paid ministry and a special building. Increasingly, however, Christians in many places are questioning whether a paid, full-time ministry is the biblical norm for all situations or just a pattern that has been uncritically transplanted from another environment. Wherever a paid ministry weakens the sense of evangelistic responsibility of all believers, it may actually retard the work of mission, however faithful the paid workers may be. In such situations the theological rediscovery of the laity as the projection of the entire congregation into the world for ministry may be as significant in the mission of both older and younger churches today as was the rediscovery of the Bible in another era.

The Church: The People Of God

The emphasis on indigenous churches must always be held in proper tension with the truth that the Church as the “People of God” is an elect race chosen out of all nations, tongues, and peoples, transcending all human relationships.

In this day of the internationalizing of missions, there are many encouraging signs of the Word at work in Asia. Asian churches are seeking to help one another. Interracial teams of Asian evangelists have begun campaigns in major cities. Churches in several countries have become “sending churches,” with their own missionaries now at work in other nations. In India, Pakistan, and the Philippines, national missionary societies have recently been organized on interdenominational lines to sponsor well-trained national Christians as missionaries to their own unevangelized areas.

All missionary work in Asia must increasingly be carried on with Asian leadership and participation. There must be an evolution from the concept of the foreign missionary society to that of missionary fellowships that know no distinction of race, color, or nationality. Future distinctions must be based solely on the ground of spiritual gifts bestowed by the one Spirit for ministry in and through the Body of Christ.

This does not mean that God’s servants from the West are any less needed, but it does mean a new partnership in obedience. It may mean that Western churches should appoint more members of Negro, American Indian, Mexican, or Oriental ancestry as missionaries, and that the Western missionary who cannot cooperate with present churches and their leaders should remain at home.

The Church: The Body Of Christ

Among both missionaries and national Christians there is a growing sense of shame and frustration over the divisions that separate even evangelical believers from one another. In India some 200 different Protestant groups are at work. While the proliferation of societies and denominations has made available a wealth of personnel and resources, the disadvantages stemming from overlapping, competition, duplication of effort, waste of funds, and lack of coordinated planning have long been apparent. All these factors contribute to an increasing recognition of the need for greater fellowship and cooperation in the work of missions throughout Asia.

Important differences, however, revolve around the nature of Christian unity and the basis of fellowship in the missionary enterprise. Where Christian unity has been interpreted organizationally, schemes of church union have already been implemented, notably in Japan, the Philippines, and South India. It is significant, however, that united churches have tended to become so preoccupied with the increased housekeeping of an enlarged family that there has been no noticeably great recovery of mission, as was hoped for and predicted. Ecumenical spokesmen themselves have begun to decry the lack of missionary vigor in the churches that make up the ecumenical movement. It is not within the united churches that one generally finds rapid church growth, great evangelistic concern, or the deepest sense of community and fellowship. This in itself raises the question whether the nature of Christian unity has been clearly and biblically understood by the organized ecumenical movement.

Evangelicals who speak of the dangers of compromise and complacency inherent in organizational union have been slow to see that the unity for which our Lord prayed in John 17, even when interpreted spiritually rather than institutionally, is a “oneness” in order that “the world might believe.” Biblical “oneness” and world evangelization are interdependent. While evangelicals have correctly pointed out that Christian unity is a given unity embracing all who are truly “in Christ,” they have not generally shown sufficient concern over the Christian’s responsibility “to maintain the unity of the Spirit in the bond of peace” (Eph. 4:3). This is due in part to a failure to recognize that the “oneness” of believers, even though spiritual, must also be visible if it is to be convincing to a lost world. There is no necessary contradiction in a unity that is spiritual and visible at the same time. Jesus taught his disciples, “By this all men will know that you are my disciples, if you have love for one another” (John 13:35). It was love that made the early Church visible to the surrounding pagans who were compelled to exclaim, “Behold, how these Christians love one another!” Wherever believers are united in faith and love the Body of Christ can be seen.

This is the essence of truly biblical ecumenicity. It lies at the heart of that which believers must again experience and demonstrate through the Holy Spirit if the Church of Jesus Christ is to continue to grow as a creative and redemptive minority in Asia and throughout the world. Its principles were summarized from Scripture long ago by the great fourth-century preacher Chrysostom, who bequeathed to all ages these memorable lines that may be commended as strategy for Asia today:

A whole Christ for my salvation.

A whole Bible for my staff.

A whole Church for my fellowship.

A whole World for my parish.

T. Leo Brannon is pastor of the First Methodist Church of Samson, Alabama. He received the B.S. degree from Troy State College and the B.D. from Emory University.