Is Christianity a friend or foe of science? Has science discredited miracles? This panel enlists three scientists in a discussion of science-and-faith concerns.

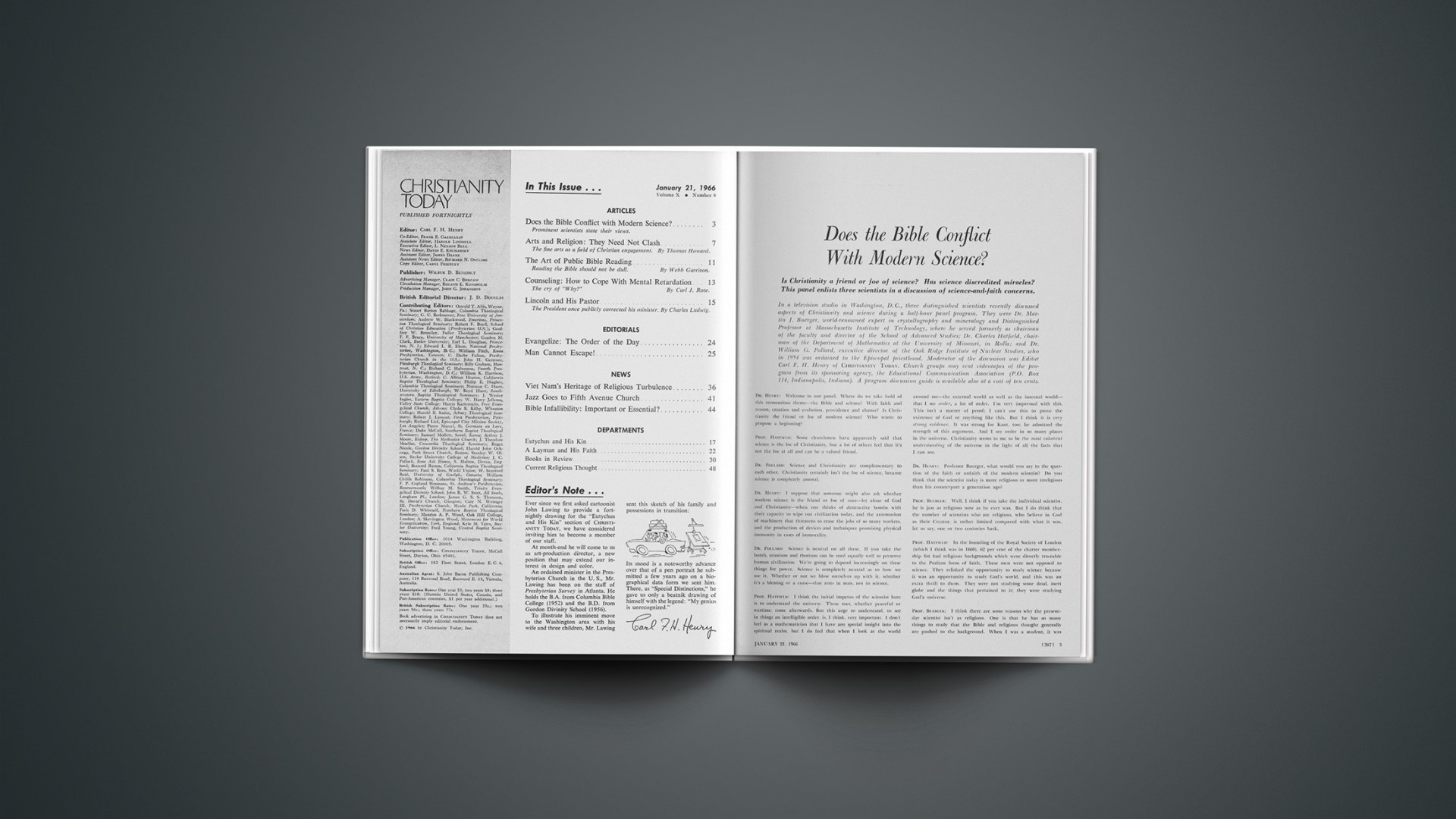

In a television studio in Washington, D. C., three distinguished scientists recently discussed aspects of Christianity and science during a half-hour panel program. They were Dr. Martin J. Buerger, world-renowned expert in crystallography and mineralogy and Distinguished Professor at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, where he served formerly as chairman of the faculty and director of the School of Advanced Studies; Dr. Charles Hatfield, chairman of the Department of Mathematics at the University of Missouri, in Rolla; and Dr. William G. Pollard, executive director of the Oak Ridge Institute of Nuclear Studies, who in 1954 was ordained to the Episcopal priesthood. Moderator of the discussion was Editor Carl F. H. Henry ofCHRISTIANITY TODAY.Church groups may rent videotapes of the program from its sponsoring agency, the Educational Communication Association (P.O. Box 114, Indianapolis, Indiana). A program discussion guide is available also at a cost of ten cents.

DR. HENRY: Welcome to our panel. Where do we take hold of this tremendous theme—the Bible and science? With faith and reason, creation and evolution, providence and chance? Is Christianity the friend or foe of modern science? Who wants to propose a beginning?

PROF. HATFIELD: Some churchmen have apparently said that science is the foe of Christianity, but a lot of others feel that it’s not the foe at all and can be a valued friend.

DR. POLLARD: Science and Christianity are complementary to each other. Christianity certainly isn’t the foe of science, because science is completely amoral.

DR. HENRY: I suppose that someone might also ask whether modern science is the friend or foe of man—let alone of God and Christianity—when one thinks of destructive bombs with their capacity to wipe out civilization today, and the automation of machinery that threatens to erase the jobs of so many workers, and the production of devices and techniques promising physical immunity in cases of immorality.

DR. POLLARD: Science is neutral on all these. If you take the bomb, uranium and thorium can be used equally well to preserve human civilization. We’re going to depend increasingly on these things for power. Science is completely neutral as to how we use it. Whether or not we blow ourselves up with it, whether it’s a blessing or a curse—that rests in man, not in science.

PROF. HATFIELD: I think the initial impetus of the scientist here is to understand the universe. These uses, whether peaceful or wartime, come afterwards. But this urge to understand, to see in things an intelligible order, is, I think, very important. I don’t feel as a mathematician that I have any special insight into the spiritual realm, but I do feel that when I look at the world around me—the external world as well as the internal world—that I see order, a lot of order. I’m very impressed with this. This isn’t a matter of proof; I can’t use this to prove the existence of God or anything like this. But I think it is very strong evidence. It was strong for Kant, too; he admitted the strength of this argument. And I see order in so many places in the universe. Christianity seems to me to be the most coherent understanding of the universe in the light of all the facts that I can see.

DR. HENRY: Professor Buerger, what would you say to the question of the faith or unfaith of the modern scientist? Do you think that the scientist today is more religious or more irreligious than his counterpart a generation ago?

PROF. BUERGER: Well, I think if you take the individual scientist, he is just as religious now as he ever was. But I do think that the number of scientists who are religious, who believe in God as their Creator, is rather limited compared with what it was, let us say, one or two centuries back.

PROF. HATFIELD: In the founding of the Royal Society of London (which I think was in 1660), 62 per cent of the charter membership list had religious backgrounds which were directly traceable to the Puritan form of faith. These men were not opposed to science. They relished the opportunity to study science because it was an opportunity to study God’s world, and this was an extra thrill to them. They were not studying some dead, inert globe and the things that pertained to it; they were studying God’s universe.

PROF. BUERGER: I think there are some reasons why the present-day scientist isn’t as religious. One is that he has so many things to study that the Bible and religious thought generally are pushed to the background. When I was a student, it was still possible for a person to become a pure research worker as he became a graduate student. But nowadays the poor graduate student is not only doing research and pursuing work towards his doctor’s degree but is also pursuing super-undergraduate work; that is, more and more knowledge has to be added to this poor man. And I think this is the same in other graduate work.

DR. POLLARD: It’s not confined to scientists; it’s a matter of our whole culture. Take lawyers or accountants or the working man; the same thing has happened in all phases apart from science. The proportion of believers has gone down in our century.

DR. HENRY: Well, in your busy life, Professor Buerger, you have felt all of these pressures. Why aren’t you numbered with those who are on the other side? Dr. Hatfield has indicated that he considers the Christian view the most coherent interpretation of the real world. Why aren’t you among the unbelieving scientists?

PROF. BUERGER: There are a lot of answers to that. One is that I was exposed to the Bible. I think that many scientists today are not exposed to the Bible for the very reason I gave, that they just don’t have time to study it in school. I very fortunately had Christian parents and I attended church, and thus I began to learn something about the Christian faith. Then, of course, I was so attracted by the beautiful coherence of the Christian faith that I followed it through. I just couldn’t keep my eyes off the Bible until I had read it through, and I continue to read it through year by year.

DR. HENRY: There’s a statement by Whitehead in Science and the Modern World.… You recall that great passage in which he says, indirectly, that Christianity is the mother of science.

DR. POLLARD: He makes quite a point that science couldn’t have arisen in a non-biblical culture. And in fact it didn’t; modern science is the product of Western Christian civilization. He has good reasons. What made modern science possible was the extraordinary enjoyment of all of God’s creatures, so that people would study a single flower. Anything that existed was interesting. Other cultures didn’t study particular things, weren’t interested in particular things.

PROF. HATFIELD: He lays heavy emphasis too, as I recall, on the inheritance from medieval culture of the idea that there was a belief—in fact, he calls it an inexpugnable belief—in the order of things, that God was behind this order, and that man had, by means of experiment, to detect that order, to cast an intellectual net and capture the regularities and the lawfulness.

DR. HENRY: When you have the polytheistic view of the Orient, in which you no longer have a single principle of explanation for all the phenomena of life but refer this to that principle, and this to that god, then you have a background in which science is impossible. But when you come to the idea of a sovereign rational mind in terms of which you are to understand the whole of reality, the Christian doctrine of creation and preservation and providence, then a mood has arisen.…

DR. POLLARD: Man is made in the image of God and therefore his mind.… He has the capacity for understanding the natural order which God created.

PROF. BUERGER: I think this matter of order is very important. I represent a science, crystallography, in which there is tremendous order. It appeals to me greatly. And I’ve questioned a number of my scientific colleagues who are also crystallographers and who are also Christians. I find that they are very much attracted to the order of the universe and cannot understand an order of the universe without a sovereign God behind it. An accidental universe which came into existence by chance seems inconceivable to them. So that we crystallographers, many of us, find that the order of the universe is the kind of thing that satisfies—the kind of thing that attracts us to crystallography order.

Faith In Rationality

“There seems but one source for the inexpugnable belief that every detailed occurrence can be correlated with its antecedents in a perfectly definite manner, exemplifying general principles.… It must come from the medieval insistence on the rationality of God.… Every detail was supervised and ordered; the search into nature could only result in the vindication of the faith in rationality.”—ALFRED NORTH WHITEHEAD, Science and the Modern World (New York: The Macmillan Company, 1946, p. 18).

DR. HENRY: Well, if at the beginning of modern science it was widely recognized that Christianity is the mother of science, why is it that today it’s more often regarded as an unwanted mother-in-law, or even as an outlaw, in relation to science? What accounts for this?

DR. POLLARD: Well, I rather think that this is the golden age of science. Science and technology are the great passion of our time, and this is a kind of prison. If you stick with a purely scientific point of view you’re trapped in nature, you can’t get out to any transcendent reality, and you are forced to rely wholly on those aspects of reality which are always and everywhere the same, which are timeless and universal. Singular events can’t have any meaning; you can’t do anything with them scientifically because you can’t repeat them or verify them. So that all of the substance of history and the sense of destiny in life and the purpose, the sense of the transcendent determinance of what happens to us, of grace and of providence and of the working out of divine purposes—all this—you have no way of dealing with it!

DR. HENRY: You’re saying in effect that since the objects of scientific study are by definition those objects which are repeatable, mechanical as it were, therefore there is …

DR. POLLARD: … that they are the same for everybody, everywhere, always.…

DR. HENRY: SO that the great biblical events, the once-for-all events, which are at the heart of biblical theology—what happens to these if you insist …

DR. POLLARD: You’re just helpless with this.

DR. HENRY: This sort of methodology screens them out arbitrarily?

DR. POLLARD: It arbitrarily screens them out.

PROF. HATFIELD: I’d like to turn to a modern-day science for what I think is an excellent illustration of the biblical concept of providence, and that is the science of cybernetics, whose father was the late Norbert Wiener. The word “cybernetics” comes from the Greek word which means governor, and the idea then is of controlling mechanism. The thermostat in our homes, for instance, tells the furnace when to kick on. This is an example of a servile mechanism, as it’s called; it governs, it controls. And the providence of God is a controlling providence. It has man’s best interests at heart. Sometimes we don’t understand things like suffering and affliction; but even this can be put in the order of things because God’s order is the heart of this matter. Even John Calvin had as his imagery for providence, the providence of God, what I think is a very well-chosen illustration. It was that of the pilot who has his eye on the waves and his hand on the wheel. He not only sees, which is what “providence” is from —pro video—but he also controls with his hand on the wheel. I think this is a wonderful picture.

DR. HENRY: Dr. Pollard, you’ve written a book on chance and providence. Why do you think the conception of providence is such a difficult one for the modern mind?

DR. POLLARD: Well, it’s again this trapping in scientific explanations. But if you stick just to science and try to give a scientific explanation of something like Dunkirk, which was a true miracle, really, all you can say is that it was “quite improbable”; it was “possible” but “improbable,” and the accident of the weather combining with other things led to this great rescue. You can’t go beyond chance and accident if you stick to a purely natural explanation.

DR. HENRY: SO that the scientific method per se doesn’t …

DR. POLLARD: It leads you to this barrier of chance and accident; that’s the boundary. And if you’re ever to get beyond that, you have to have supernatural, transcendent determinance of history. But many of the people involved in Dunkirk will tell you now, they know that God was operative in the passion, and the accidents in the way everything fell in place. And that’s the way miracle occurs. Things fall in place in the most “accidental” and improbable ways. Science can tell you what is most likely to happen, and most of the time what’s most likely to happen does happen. But the great creative factors in any history or in a person’s life are the great accidents, the great improbables. And that’s where providence reveals itself.

DR. HENRY: Would you care to spell out a bit the limits of the scientific method? When a scientist rails against the supernatural and against the miraculous, he certainly doesn’t do so on the basis of any …

What Of Providence?

“Among the several key elements of the historic Christian faith which are difficult for the modern mind, there is none so remote from contemporary thought forms as the notion of providence.…”—WILLIAM G. POLLARD, Chance and Providence: God’s Action in a World Governed by Scientific Thought (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1958, p. 17).

DR. POLLARD: … of any science. Because science by definition is the study of nature. It can’t get beyond three-dimensional space and time, all objects and events in space and time. That’s the domain of science. It has no competence to transcend space and time. So it can’t say whether reality transcendent to space and time exists or doesn’t exist. It has no competence in this.

PROF. BUERGER: The thing. I think, that repels many scientists about the miracles is that they never happened before. But I think this is a rather invalid point of view.

DR. POLLARD: I do, too.

PROF. BUERCER: Because as new scientific discoveries are made, the most improbable things become the realities. One of the things that has struck me because it happened during my lifetime was the discovery of the duality of the particle—that it is both a wave and a particle. It sometimes behaves as if it has mass; on other occasions it behaves as if it has a wave length and a frequency. And if there is anything more improbable than the same thing doing two different things in two different ways, I can’t think of it.

DR. POLLARD: A lot of people today have an image of science based on the science of the nineteenth century, or the early part of this century, when nature seemed shallow and science was rapidly getting at the one great formula, at the secret of things that lay just below the surface. Now we’ve gone deeper and deeper and to lower and lower levels. Every mystery that science clears up opens up ten more questions, and it’s a divergent series. The world seems very strange and weird in modern astronomy and physics, the structure of matter. We’re just led on deeper—more and more mysterious and strange—like your wave and particle. It’s really quite mysterious.

PROF. BUERGER: Well, this is a very interesting point of view, this divergent series. I never thought of it in this way. But you know good research is judged by how many other bits of research …

DR. POLLARD: … how many other questions it opens up.

PROF. BUERGER: HOW many times it reduplicates itself. And this is surely true of modern science. It opens more questions than it answers.

DR. HENRY: When you speak of miracles in this way, you apparently suggest that the scientist has no need to whisper about miracles. Some of the modern theologians are whispering about miracles, even about God. You have the death-of-God school today, as well as the death of miracles and everything else. Now when you say that the scientist has no need, on the basis of anything that science uncovers for him, to whisper about miracles, do you mean the great biblical miracles here, the miracles that are at the heart of the Christian religion?

DR. POLLARD: Surely.

DR. HENRY: The virgin birth of Christ, the bodily resurrection …?

DR. POLLARD: The incarnation, his resurrection, his ascension, the exodus, the exile—there are any number. That’s the heart of biblical theology.

PROF. HATFIELD: Because the miracle does excite wonder and awe by its unusual character, sometimes the real setting of it is lost sight of. I think that the purpose of the miracle in the Bible is an evidence for truth.… In the Old Testament the people were warned against accepting the merely miraculous. They were to examine very closely what the message was that went along with that alleged miracle.

DR. POLLARD: In the New Testament they kept asking Christ, Jesus, for signs and wonders, and he said no sign or wonder was going to be given. The character of the miracle there was deeply revelatory; it was something God was doing, and not just a great sign.

DR. HENRY: Or just a display of power. The miracles were this, a display of vast power. But more than this they were meaningful; they were signs, weren’t they, in the New Testament?

PROF. HATFIELD: The key is the purpose of the miracle, the purpose as understood in the truth which God was trying to communicate to us, whether through a personal dimension or through something in the universe. The key is the purpose, the purpose of God. If we understand the miracle this way, then there is a strong argument for its being understood; it’s put in the proper setting. The setting is not natural science; the setting is the will of God for the miracle, and if we look at it that way, it becomes much more intelligible, I think.

PROF. BUERGER: This is very much like saying that the Bible is hardly a textbook of science so you don’t go there to find your scientific information, although many of the things predicted there have been remarkably fulfilled. Nor is science a textbook of religion; it does not tell of God. The Bible and science are, as we mathematicians say, orthogonal to each other. They have nothing to do with each other necessarily.

PROF. HATFIELD: And it’s the misunderstanding of these purposes, the purpose of science and the purpose of the Bible, I think, that has gotten us into difficulty in the past. Luther was found in an embarrassing posture of criticizing Copernicus when he put forth his view with regard to the center of the universe being the sun rather than the earth. The conflict is not between the Bible and science. The conflict is between what people say the Bible says and what people say science says, and this has to be kept in mind.

DR. POLLARD: There are a lot of misunderstandings there. You know, I think one can’t really fully appreciate the biblical miracles without having a deep sense of the miraculous in one’s own life, a sense that great and wonderful things happen. Take the whole history of life on this earth that we call evolution. It’s a miraculous chain of events, really, to take DNA codes and go from single cells through great improbabilities and many accidents and have this work its way up through a really creative process, leading ultimately to man—which is a real phenomenon. It’s just a miraculous thing. And if you get this sense of the miraculous in all history, then this is the biblical context. When you approach the Bible from this kind of context, it seems natural and it comes alive.

DR. HENRY: And in all this order the fixed purpose of God worked through it. I think for example of a comment by Oswald Spengler in The Decline of the West. He says, you remember, that the most devastating refutation that he knew of Darwin’s premise that all the complex forms of life have emerged by slow, gradual, almost imperceptible change from simpler forms, is the fact that what we actually find in the paleontological record is the aboriginal forms which have survived through the long periods. It is not all a matter of fluidity.

Well, we have nearly come to the end of our time, but I think there is a moment for a closing statement by each member of the panel.

PROF. BUERGER: I think the Bible is a remarkable book, and not just as literature. It’s something worth studying, especially in this space age. So I would recommend to those who haven’t taken it seriously, in the words of the prophets: “Seek him who maketh seven stars in Orion. The Lord is his name.” The Bible tells about this. I think every scientist should know about this.

PROF. HATFIELD: I think the key to the question of the Bible and science is that each must be understood in terms of its own purpose. The Bible tells us that God created the universe, and science helps us to understand something of how this took place. There is no need for a conflict here. The categories of the Bible are the categories of good and evil, mercy, judgment, sin, salvation. The categories of science, on the other hand, are in terms of mass, energy, and the laws that we get from them. These two need not conflict at all.

DR. POLLARD: Well, to me they complement each other. Either without the other is a restricted view of the whole of reality. Science has opened up our understanding of the natural order of the universe. The Bible opens up our understanding of that which transcends the universe.

DR. HENRY: Thank you very much. We have scarcely exhausted our theme, I know, but we have surely suggested areas for further study in this field of the Bible and science. We have said that the Bible is not a textbook on science. If it were, it would have to be revised many times. And we have also said that modern science has not destroyed any of the great truths of the Christian religion. Modern man would not be modern were it not for the changes of science. But he would surely be less than a whole man did he not appropriate the realities of true religion.

Reply To Darwin

“There is no more conclusive refutation of Darwinism than that furnished by paleontology. Simple probability indicates that fossil hoards can only be test samples. Each sample, then, should represent a different stage of evolution, and there ought to be merely ‘transitional’ types, no definition and no species. Instead of this we find perfectly stable and unaltered forms persevering through long ages, forms that have not developed themselves on the fitness principle, but appear suddenly and at once in their definitive shape; that do not thereafter evolve towards better adaptation, but become rarer and finally disappear, while different forms crop up again. What unfolds itself, in ever-increasing richness of form, is the great classes and kinds of living beings which exist aboriginally and exist still, without transition types, in the grouping of to-day.”—OSWALD SPENCLER, The Decline of the West (New York: Knopf, 1934, Vol. II, p. 32).