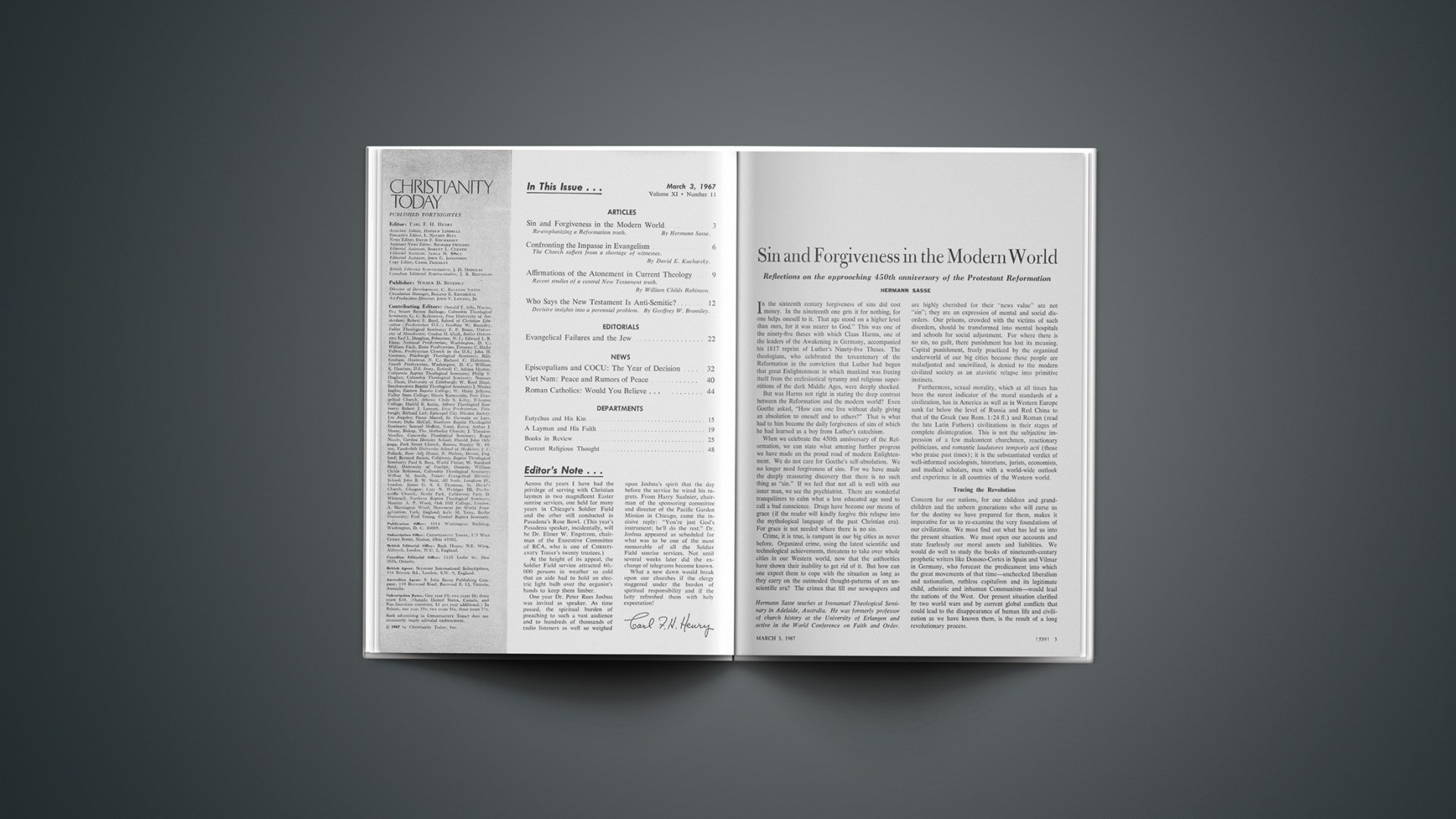

Reflections on the approaching 450th anniversary of the Protestant Reformation

In the sixteenth century forgiveness of sins did cost money. In the nineteenth one gets it for nothing, for one helps oneself to it. That age stood on a higher level than ours, for it was nearer to God.” This was one of the ninety-five theses with which Claus Harms, one of the leaders of the Awakening in Germany, accompanied his 1817 reprint of Luther’s Ninety-five Theses. The theologians, who celebrated the tercentenary of the Reformation in the conviction that Luther had begun that great Enlightenment in which mankind was freeing itself from the ecclesiastical tyranny and religious superstitions of the dark Middle Ages, were deeply shocked.

But was Harms not right in stating the deep contrast between the Reformation and the modern world? Even Goethe asked, “How can one live without daily giving an absolution to oneself and to others?” That is what had to him become the daily forgiveness of sins of which he had learned as a boy from Luther’s catechism.

When we celebrate the 450th anniversary of the Reformation, we can state what amazing further progress we have made on the proud road of modern Enlightenment. We do not care for Goethe’s self-absolution. We no longer need forgiveness of sins. For we have made the deeply reassuring discovery that there is no such thing as “sin.” If we feel that not all is well with our inner man, we see the psychiatrist. There are wonderful tranquilizers to calm what a less educated age used to call a bad conscience. Drugs have become our means of grace (if the reader will kindly forgive this relapse into the mythological language of the past Christian era). For grace is not needed where there is no sin.

Crime, it is true, is rampant in our big cities as never before. Organized crime, using the latest scientific and technological achievements, threatens to take over whole cities in our Western world, now that the authorities have shown their inability to get rid of it. But how can one expect them to cope with the situation as long as they carry on the outmoded thought-patterns of an unscientific era? The crimes that fill our newspapers and are highly cherished for their “news value” are not “sin”; they are an expression of mental and social disorders. Our prisons, crowded with the victims of such disorders, should be transformed into mental hospitals and schools for social adjustment. For where there is no sin, no guilt, there punishment has lost its meaning. Capital punishment, freely practiced by the organized underworld of our big cities because these people are maladjusted and uncivilized, is denied to the modern civilized society as an atavistic relapse into primitive instincts.

Furthermore, sexual morality, which at all times has been the surest indicator of the moral standards of a civilization, has in America as well as in Western Europe sunk far below the level of Russia and Red China to that of the Greek (see Rom. 1:24 ff.) and Roman (read the late Latin Fathers) civilizations in their stages of complete disintegration. This is not the subjective impression of a few malcontent churchmen, reactionary politicians, and romantic laudatores temporis acti (those who praise past times); it is the substantiated verdict of well-informed sociologists, historians, jurists, economists, and medical scholars, men with a world-wide outlook and experience in all countries of the Western world.

Tracing The Revolution

Concern for our nations, for our children and grandchildren and the unborn generations who will curse us for the destiny we have prepared for them, makes it imperative for us to re-examine the very foundations of our civilization. We must find out what has led us into the present situation. We must open our accounts and state fearlessly our moral assets and liabilities. We would do well to study the books of nineteenth-century prophetic writers like Donoso-Cortes in Spain and Vilmar in Germany, who forecast the predicament into which the great movements of that time—unchecked liberalism and nationalism, ruthless capitalism and its legitimate child, atheistic and inhuman Communism—would lead the nations of the West. Our present situation clarified by two world wars and by current global conflicts that could lead to the disappearance of human life and civilization as we have known them, is the result of a long revolutionary process.

During the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries the revolution became visible in the Renaissance, which must be understood as the great secular counter-movement against the attempt of the Middle Ages to build a Christian world. This attempt, like all similar ones in later times, ended not in the Christianization of the world but in the secularization of the Church. The world did not become Church; rather, the Church became world. The Reformation was in its deepest nature an attempt to save the Church from that destiny.

But the revolution went on. It appeared again as a mighty power in the Enlightenment of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries and won its first great victory in the French Revolution of 1789, that great earthquake which was to be followed by minor quakes and by the nationalist and Communist revolutions of the twentieth century.

A revolution is not necessarily destructive; witness the American Revolution, which gave birth to a new nation. This, like the English revolution of the seventeenth century, maintained something that was lost in the French Revolution and in the history that followed it: the recognition of standards and principles that are not made by man but are given to him. On this recognition of standards, norms, and orders not made by men rests all human life. It is the basis of all lasting communities and all lasting human institutions: family, nation, authority of the law, legislation and judiciary. In whatever forms men may have interpreted or misinterpreted it in their religions, schools of wisdom, and philosophical and sociological systems, this phenomenon that the Bible calls the law written in all men’s hearts (Rom. 2:14, 15) is their common possession. They all have thought in terms of right and wrong, good and evil, vice and virtue, keeping and breaking the law, justice, guilt, sin, judgment, punishment, satisfaction.

But it was the privilege of modern mankind—or, more accurately, of the modern, Western, “Christian” world—to deny and to destroy these basic concepts of human life and thought. This is the great revolution that began in the neo-pagan Renaissance, developed in the philosophy of Enlightenment, and found its first visible manifestation when the French Revolution of 1789 started the series of modern revolutions that swept through Europe from west to east and began to spread through the entire world, threatening not only old forms of human life but all human life on earth. Not the violation of eternal laws (which has happened and will happen at all times) but the denial of the existence of such laws—this is at the heart of the great revolution that began in the quiet studies of writers such as Voltaire, Rousseau, Hegel, Marx, and Nietzsche and showed its true face in the horrors of the French, Russian, and German revolutions.

The End Of Sin-Consciousness

It is this great revolution, the abolition of eternal laws that are binding on all men and all ages, that has destroyed the consciousness of sin and the understanding of forgiveness, even in the Christian churches. History shows that the disintegration of a civilization, the decay of nations, the moral and spiritual bankruptcy of the world in which the earthly Church lives, always are reflected in the life of the Church. This is naturally so, because the members of the Church live in the world and are as weak and sinful men exposed to all temptations of the world.

This explains the strange role clergymen have played in all revolutions. The Catholic clergy in France in 1789 and the German clergy of all churches in 1933 welcomed their revolutions with equal enthusiasm. The same picture is presented today by the American clergy of all denominations who participate in those big-city demonstrations and fights that may later be called the beginning of another American revolution. Among the ideologists who pave the way for a revolution, there have always been some theologians, even in Russia. He who saw the heyday of the social gospel in America forty years ago (“The flag of the Kingdom of God is red, symbolizing the common blood of all mankind,” said Brewster in The Simple Gospel) is not astonished to see the harvest of Rauschenbusch’s theology.

Every pastor and every Christian layman with pastoral experience knows that many more people are still trembling before the judgment of God and longing for forgiveness than the theoreticians on our theological faculties are inclined to believe; however, they are a minority in our churches. It is true that, as Tholuck claimed, an indulgence salesman, should he turn up today, would bitterly complain about the decline of his trade and soon be forced out of business. This may be one of the reasons why the Tetzels of our time have had to develop better and more dignified methods of “selling the Gospel.” (We should not, in this ecumenical age, entirely deny our sympathy to John Tetzel, to whom even Luther addressed a letter of consolation shortly before his death in 1519. Tetzel regarded his job as soul-winning evangelism. Although his sense of business was certainly over-developed, he never solicited money from people without income, such as housewives. And he was one of the first to practice proportional giving.)

It is most certainly true that the average man of our day no longer understands what sin and grace, judgment and justification are. But how do we explain that this is also true of so many people who profess to be and seriously want to be Christians, and who go to church, listen to the sermon, and receive the sacraments?

Part of the answer is that the great process of secularization has transformed not only human souls but also the institutions of our social life. Serious Christians and also serious non-Christians of deep moral convictions are to be found in all walks of life. Why are they unable to change the course of things, even in a democratic society—and perhaps even less in democracies than in other forms of society?

To understand this, we take the example of a judge. Our law courts are full of excellent men, exemplary judges with all the virtues a judge ought to have. But they have to apply the existing laws, which they have not made and cannot alter. If these laws are bad, even the best judiciary cannot safeguard law and order in a nation. The institutions are stronger than the individual. This is true of all social institutions, good or bad.

It is true also of ecclesiastical institutions, from the local congregation to the biggest church body, from the office of a pastor or elder to the highest offices of church government. If a church body is in a state of disintegration and decay, the spiritual life of the individual Christians must suffer. Here lies the reason why, despite the great number of believing Christians in church and state and in all public offices and functions of our society, the decay of our Western world seems irrevocable.

One Message

The message of the Reformation sounds through a dying world. It is an eternal message, for rightly understood it is the Gospel itself. “Repent and believe in the Gospel” (Mark 1:15b, RSV). So began the preaching of our Lord. “Repent, and be baptized every one of you in the name of Jesus Christ for the forgiveness of your sins …” (Acts 2:30). So began the preaching of the Apostles at Pentecost. “Our Lord and Master Jesus Christ in saying ‘Repent ye, etc.’ meant the whole life of the faithful to be an act of repentance.” With this first of the Ninety-five Theses began the Reformation. Every new epoch in the history of the Church, every great revival, began with the same call to repentance and faith in the Gospel.

Indeed, we have no other message. The Church may have a lot to say on the affairs of men, applying the eternal law of God to the everyday life of men and women, parents and children, state and nation, and all human institutions. This is important and necessary, for the Church of Jesus Christ has also to proclaim and interpret the Law as God’s Word. However, this does not mean that the Church can solve the problems of mankind, draw up constitutions for state and society, proclaim a new social and economic order, and establish a theocracy. Whenever such attempts have been made, whether in the Middle Ages or by later sects or by the prophets of the social gospel in America, the Church has overstepped its rights and duties and ceased to be Church, because it has lost the Gospel.

The essential function of the Church is to preach the Gospel: “The true treasure of the Church is the sacrosanct Gospel of the glory and grace of God,” Luther’s thesis 62 says. And to avoid any misunderstanding, he defines this Gospel as the forgiveness of sins: “Without rashness we say that the keys of the Church, given by the merit of Christ, are that treasure” (thesis 60).

The Gospel, strictly speaking, is not a message that there is forgiveness, not a theory of forgiveness, but the forgiveness itself, the absolution Christ gives to the believing sinner. “Thy sins are forgiven unto thee.” When our Lord said this to a sinner, the Gospel proper was heard in Galilee. It met at once with unbelief and contradiction: “It is a blasphemy! Who can forgive sins but God alone?” Here in the earliest days of Jesus’ ministry, already the whole Gospel with all its implications and consequences is present. The mystery of his person, his power, his cross, and his eternal glory shine through the simple narrative of Mark 2 when Jesus demonstrates his authority “that you may know that the Son of man has authority on earth to forgive sins.” As the Risen One, he passes on his mission and his authority to his disciples: “As the Father has sent me, even so I send you.… Receive the Holy Spirit. If you forgive the sins of any, they are forgiven; if you retain the sins of any, they are retained” (John 20:22b, 23).

To commemorate the Reformation means to remember the Gospel of the glory and grace of Christ, the forgiveness of sins in the name of him who alone has the power to forgive sins because he is the Lamb of God who takes away the sins of the world. The Reformers did not know of any other Gospel. There is none.

The question, What is the essence of Christianity?, has often been discussed. Any answer is wrong that fails to realize that one thing distinguishes the Christian Church and the Christian faith from all other religions and “ways” of salvation in the history of mankind. Great mysticism is found in many religions; splendid ethics may be found in Buddhism or with the thinkers of ancient China; touching liturgies were found in the mystery religions that surrounded the early Church. The Christian sacraments are simple and inconspicuous compared with the holy rites of Asian religions. The Egyptian cult of Isis and Osiris with its promise of eternal life had such a power over the souls of men that the name “Isidor” has for centuries remained popular even in the Christian world. If the fight against alcohol and racial segregation is the mark of true religion, then Islam must be regarded as superior to Christianity.

What, then, attracted the people in the Roman Empire, first the slaves and the lower classes, but soon men of highest education? Why did they join, at the risk of their lives, the despised and forbidden “sect” of the Christians? Because it offered to them what no other religion, not even the synagogue, could offer: the forgiveness of their sins in the name of him who had loved each one of them so that he even died for them. This is the secret of the Gospel and its victories in the history of mankind.

Can We Understand Sin?

Today people no longer understand what sin is. Even the Christians have become very weak in their understanding of it. One can observe this in the Roman church by comparing the doctrine of sin in the decisions of Trent, which were deeply influenced by the Reformation, with the concept of sin underlying the decrees of the Second Vatican Council, which was deeply influenced by the enlightened mind of the modern world. And one may see this weakness in the Lutheran churches that in the Assembly of Helsinki agreed in recognizing justification as the center of their faith but could not agree on what justification is.

Sin is the great reality in all human life, and the greatest sin is not to believe in Jesus. Righteousness is a divine reality, not a product of human thought. There is judgment going over the world, and there will be a final judgment of all men. Of this the Holy Spirit will convince the proud, sick, dying modern world—and the modern world that lives in each of us.