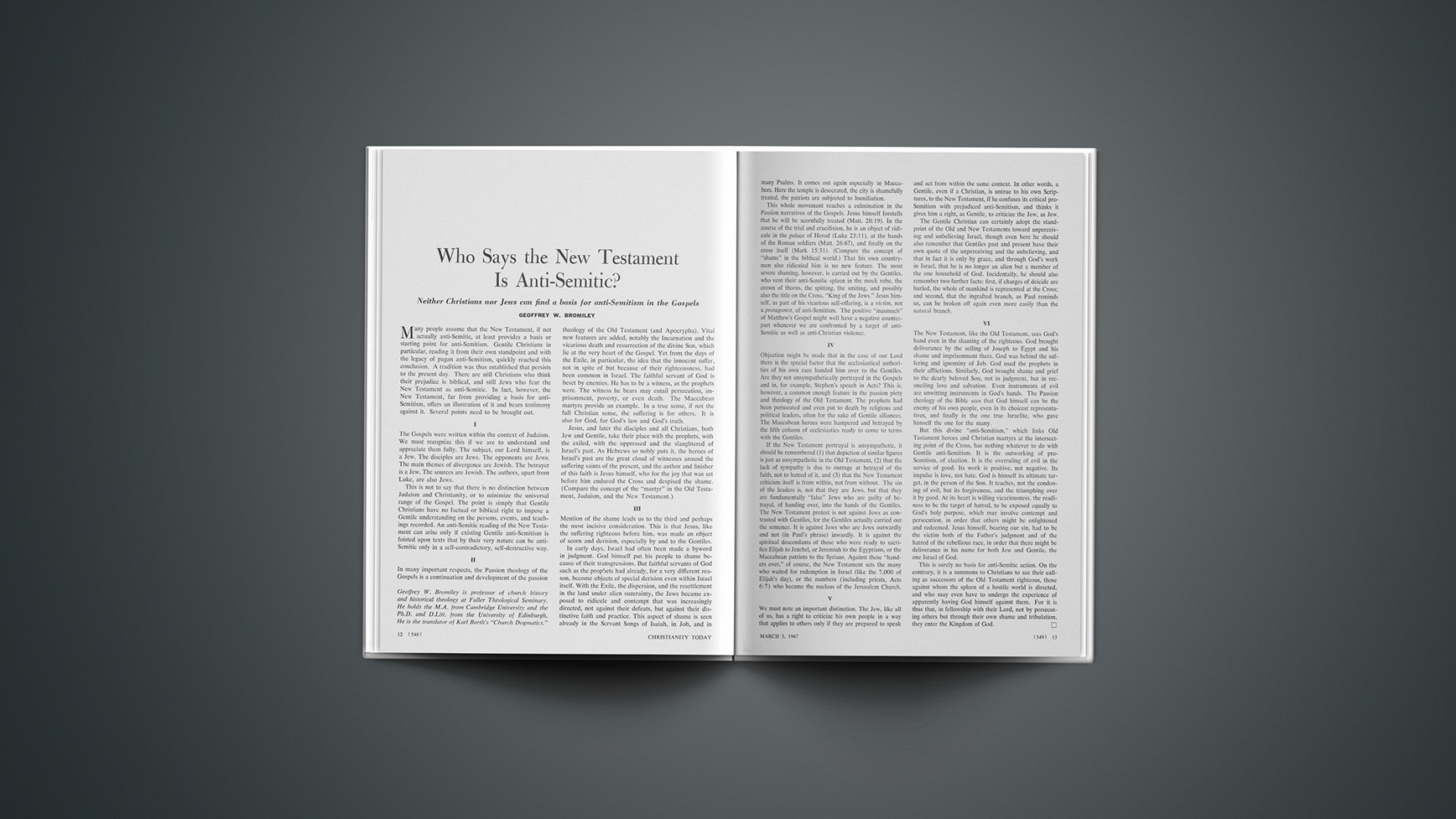

Neither Christians nor Jews can find a basis for anti-Semitism in the Gospels

Many people assume that the New Testament, if not actually anti-Semitic, at least provides a basis or starting point for anti-Semitism. Gentile Christians in particular, reading it from their own standpoint and with the legacy of pagan anti-Semitism, quickly reached this conclusion. A tradition was thus established that persists to the present day. There are still Christians who think their prejudice is biblical, and still Jews who fear the New Testament as anti-Semitic. In fact, however, the New Testament, far from providing a basis for anti-Semitism, offers an illustration of it and bears testimony against it. Several points need to be brought out.

I

The Gospels were written within the context of Judaism. We must recognize this if we are to understand and appreciate them fully. The subject, our Lord himself, is a Jew. The disciples are Jews. The opponents are Jews. The main themes of divergence are Jewish. The betrayer is a Jew. The sources are Jewish. The authors, apart from Luke, are also Jews.

This is not to say that there is no distinction between Judaism and Christianity, or to minimize the universal range of the Gospel. The point is simply that Gentile Christians have no factual or biblical right to impose a Gentile understanding on the persons, events, and teachings recorded. An anti-Semitic reading of the New Testament can arise only if existing Gentile anti-Semitism is foisted upon texts that by their very nature can be anti-Semitic only in a self-contradictory, self-destructive way.

Ii

In many important respects, the Passion theology of the Gospels is a continuation and development of the passion theology of the Old Testament (and Apocrypha). Vital new features are added, notably the Incarnation and the vicarious death and resurrection of the divine Son, which lie at the very heart of the Gospel. Yet from the days of the Exile, in particular, the idea that the innocent suffer, not in spite of but because of their righteousness, had been common in Israel. The faithful servant of God is beset by enemies. He has to be a witness, as the prophets were. The witness he bears may entail persecution, imprisonment, poverty, or even death. The Maccabean martyrs provide an example. In a true sense, if not the full Christian sense, the suffering is for others. It is also for God, for God’s law and God’s truth.

Jesus, and later the disciples and all Christians, both Jew and Gentile, take their place with the prophets, with the exiled, with the oppressed and the slaughtered of Israel’s past. As Hebrews so nobly puts it, the heroes of Israel’s past are the great cloud of witnesses around the suffering saints of the present, and the author and finisher of this faith is Jesus himself, who for the joy that was set before him endured the Cross and despised the shame. (Compare the concept of the “martyr” in the Old Testament, Judaism, and the New Testament.)

Iii

Mention of the shame leads us to the third and perhaps the most incisive consideration. This is that Jesus, like the suffering righteous before him, was made an object of scorn and derision, especially by and to the Gentiles.

In early days, Israel had often been made a byword in judgment. God himself put his people to shame because of their transgressions. But faithful servants of God such as the prophets had already, for a very different reason, become objects of special derision even within Israel itself. With the Exile, the dispersion, and the resettlement in the land under alien suzerainty, the Jews became exposed to ridicule and contempt that was increasingly directed, not against their defeats, but against their distinctive faith and practice. This aspect of shame is seen already in the Servant Songs of Isaiah, in Job, and in many Psalms. It comes out again especially in Maccabees. Here the temple is desecrated, the city is shamefully treated, the patriots are subjected to humiliation.

This whole movement reaches a culmination in the Passion narratives of the Gospels. Jesus himself foretells that he will be scornfully treated (Matt. 20:19). In the course of the trial and crucifixion, he is an object of ridicule in the palace of Herod (Luke 23:11), at the hands of the Roman soldiers (Matt. 26:67), and finally on the cross itself (Mark 15:31). (Compare the concept of “shame” in the biblical world.) That his own countrymen also ridiculed him is no new feature. The most severe shaming, however, is carried out by the Gentiles, who vent their anti-Semitic spleen in the mock robe, the crown of thorns, the spitting, the smiting, and possibly also the title on the Cross, “King of the Jews.” Jesus himself, as part of his vicarious self-offering, is a victim, not a protagonist, of anti-Semitism. The positive “inasmuch” of Matthew’s Gospel might well have a negative counterpart whenever we are confronted by a target of anti-Semitic as well as anti-Christian violence.

Iv

Objection might be made that in the case of our Lord there is the special factor that the ecclesiastical authorities of his own race handed him over to the Gentiles. Are they not unsympathetically portrayed in the Gospels and in, for example, Stephen’s speech in Acts? This is, however, a common enough feature in the passion piety and theology of the Old Testament. The prophets had been persecuted and even put to death by religious and political leaders, often for the sake of Gentile alliances. The Maccabean heroes were hampered and betrayed by the fifth column of ecclesiastics ready to come to terms with the Gentiles.

If the New Testament portrayal is unsympathetic, it should be remembered (1) that depiction of similar figures is just as unsympathetic in the Old Testament, (2) that the lack of sympathy is due to outrage at betrayal of the faith, not to hatred of it, and (3) that the New Testament criticism itself is from within, not from without. The sin of the leaders is, not that they are Jews, but that they are fundamentally “false” Jews who are guilty of betrayal, of handing over, into the hands of the Gentiles. The New Testament protest is not against Jews as contrasted with Gentiles, for the Gentiles actually carried out the sentence. It is against Jews who are Jews outwardly and not (in Paul’s phrase) inwardly. It is against the spiritual descendants of those who were ready to sacrifice Elijah to Jezebel, or Jeremiah to the Egyptians, or the Maccabean patriots to the Syrians. Against these “handers over,” of course, the New Testament sets the many who waited for redemption in Israel (like the 7,000 of Elijah’s day), or the numbers (including priests, Acts 6:7) who became the nucleus of the Jerusalem Church.

V

We must note an important distinction. The Jew, like all of us, has a right to criticize his own people in a way that applies to others only if they are prepared to speak and act from within the same context. In other words, a Gentile, even if a Christian, is untrue to his own Scriptures, to the New Testament, if he confuses its critical pro-Semitism with prejudiced anti-Semitism, and thinks it gives him a right, as Gentile, to criticize the Jew, as Jew.

The Gentile Christian can certainly adopt the standpoint of the Old and New Testaments toward unperceiving and unbelieving Israel, though even here he should also remember that Gentiles past and present have their own quota of the unperceiving and the unbelieving, and that in fact it is only by grace, and through God’s work in Israel, that he is no longer an alien but a member of the one household of God. Incidentally, he should also remember two further facts: first, if charges of deicide are hurled, the whole of mankind is represented at the Cross; and second, that the ingrafted branch, as Paul reminds us, can be broken off again even more easily than the natural branch.

Vi

The New Testament, like the Old Testament, sees God’s hand even in the shaming of the righteous. God brought deliverance by the selling of Joseph to Egypt and his shame and imprisonment there. God was behind the suffering and ignominy of Job. God used the prophets in their afflictions. Similarly, God brought shame and grief to the dearly beloved Son, not in judgment, but in reconciling love and salvation. Even instruments of evil are unwitting instruments in God’s hands. The Passion theology of the Bible sees that God himself can be the enemy of his own people, even in its choicest representatives, and finally in the one true Israelite, who gave himself the one for the many.

But this divine “anti-Semitism,” which links Old Testament heroes and Christian martyrs at the intersecting point of the Cross, has nothing whatever to do with Gentile anti-Semitism. It is the outworking of pro-Semitism, of election. It is the overruling of evil in the service of good. Its work is positive, not negative. Its impulse is love, not hate. God is himself its ultimate target, in the person of the Son. It teaches, not the condoning of evil, but its forgiveness, and the triumphing over it by good. At its heart is willing vicariousness, the readiness to be the target of hatred, to be exposed equally to God’s holy purpose, which may involve contempt and persecution, in order that others might be enlightened and redeemed. Jesus himself, bearing our sin, had to be the victim both of the Father’s judgment and of the hatred of the rebellious race, in order that there might be deliverance in his name for both Jew and Gentile, the one Israel of God.

This is surely no basis for anti-Semitic action. On the contrary, it is a summons to Christians to see their calling as successors of the Old Testament righteous, those against whom the spleen of a hostile world is directed, and who may even have to undergo the experience of apparently having God himself against them. For it is thus that, in fellowship with their Lord, not by persecuting others but through their own shame and tribulation, they enter the Kingdom of God.