NEWS

Once Madalyn Murray O’Hair had knocked school devotional life into a tizzy, Presbyterian-Reformed Senator Everett M. Dirksen (R.-Ill.) battled to let Americans demonstrate their faith on tax-supported property. Then, when Dirksen died, his Presbyterian son-in-law, Senator Howard H. Baker (R.-Tenn.), took up the cudgel. Dirksen came within six votes of the two-thirds needed in the Senate to get the bill on the way, to its next big hurdle.

On the House side, meantime, a similar but stronger measure was bottled up for eight years in the House Judiciary Committee. Representative Emanuel Celler, 83 (D.-N.Y.), said he couldn’t produce a wording that his committee deemed constitutional.

But when Representative Charles J. Carney (D.-Ohio) provided the 218th signature to a discharge petition, the proposal suddenly found new life; it was automatically sent to the House for a vote. On November 8 the House reaffirmed the discharge of the committee by voting 242 to 156 to consider the issue immediately. Two hours after that vote, when the smoke and rhetoric had cleared, the final vote on the proposed constitutional amendment (it would have been the first change in the Bill of Rights) was 240 to 162, 28 short of the required two-thirds.1After clearance by the House, it would still have had to go through the Senate (also by a two-thirds majority), then pass in three-fourths of the states within seven years of congressional approval.

The amendment, as first put to the House, read: “Nothing contained in this Constitution shall abridge the right of persons lawfully assembled, in any public building which is supported in whole or in part through expenditure of public funds, to participate in nondenominational prayer.”

But the prayer proposal’s chief sponsor, Representative Chalmers P. Wylie (R.-Ohio), aware that his forces lacked the necessary two-thirds, acceded to the substitution of “voluntary prayer and meditation” for “nondenominational prayer.” Critics had asserted that “nondenominational” either was impossible to define or was a threat to—rather than a safeguard of—religious freedom. The change from “nondenominational” to “voluntary” was offered by Representative John Buchanan (R.-Ala.), a Baptist minister—one of the two clergymen in the House.

The other, Robert F. Drinan (D.-Mass.), vociferously opposed the entire amendment. The Jesuit priest and former dean of Boston College’s School of Law charged that its passage would create an “ersatz religion” dictated by government.

Thus, with Mosaic caution, the 402 congressmen who voted apparently laid to rest the long-standing move to strike down Supreme Court decisions in 1962 and 1963 that outlawed government-supervised prayers in public schools as violating the freedom-of-religion guarantee of the First Amendment.

Did the “religious lobby,” as some claimed after the vote, sway the House against the amendment? No fewer than thirty-eight major religious bodies opposed the amendment. And within the House, some of the most actively religious congressmen frowned on the amendment. Among them was Iowa Republican Fred Schwengel, a Baptist said to carry seventeen prayers in his coat pocket. “I believe in the great bulwark of separation of church and state,” he said after the vote. “I think we’d lower the quality of prayer if we let the state write it.”

Pro-prayer amendment forces frequently quoted polls indicating that the “people” were strongly in favor of the amendment, and argued that, if prayer is disallowed in the schools, the next step will be to remove prayers at the beginning of each session of Congress and the motto “In God we trust” from above the House Speaker’s chair.

Those favoring the amendment were various individual churchmen, including Billy Graham, and the National Association of Evangelicals. NAE general secretary Clyde Taylor said the amendment would “not promote or inhibit prayer by anyone.… It will restore the freedom of persons to pray in public places when and if it is appropriate.”

After the final vote was announced, a disgruntled middle-aged woman in the visitors’ gallery muttered: “Atheists, atheists! They’re making an atheist country.”

But the roll-call vote revealed that the representatives voted more along party than religious lines (with a few exceptions), according to the announced stands of the religious bodies with which the congressmen are affiliated.

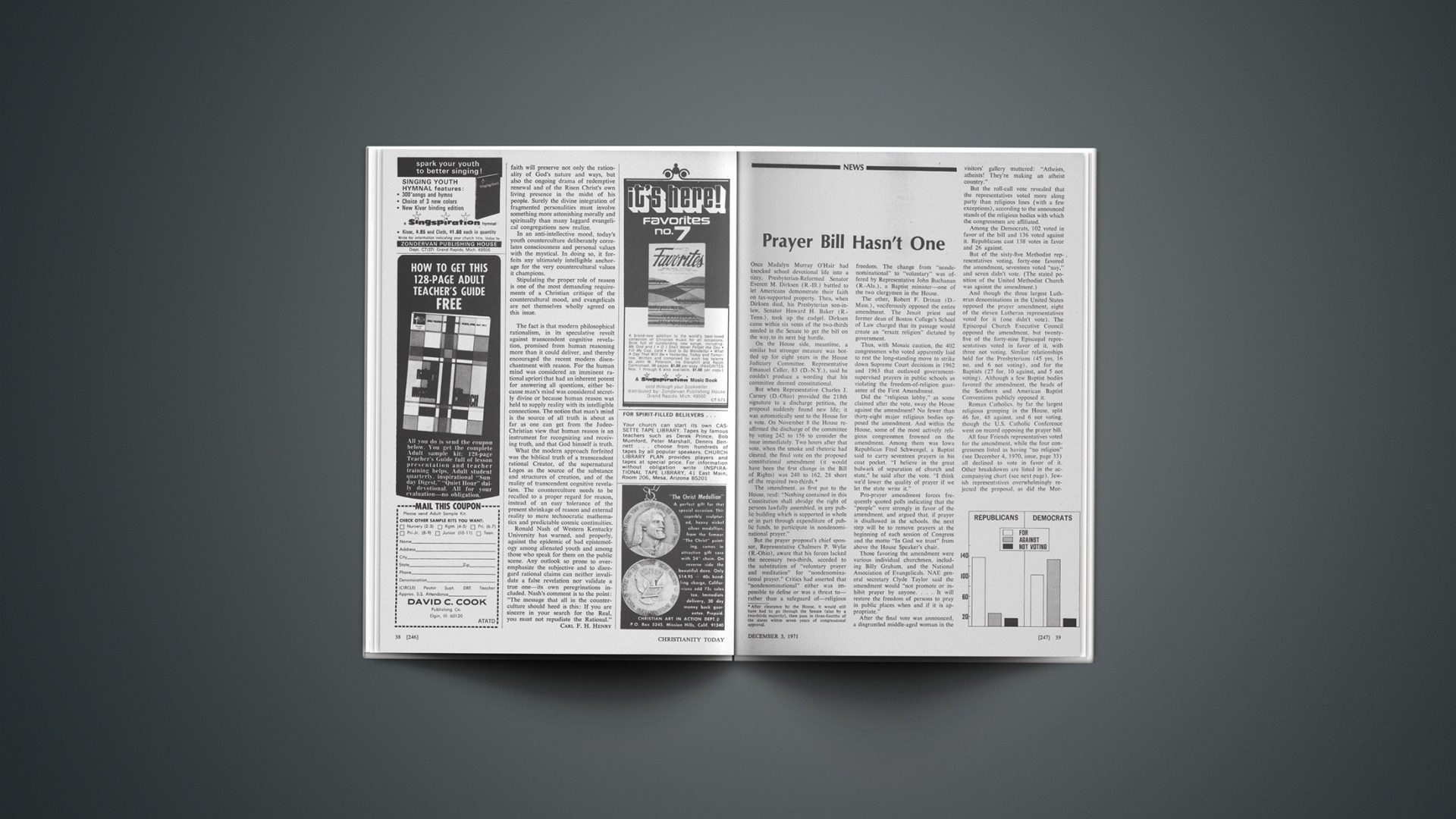

Among the Democrats, 102 voted in favor of the bill and 136 voted against it. Republicans cast 138 votes in favor and 26 against.

But of the sixty-five Methodist representatives voting, forty-one favored the amendment, seventeen voted “nay,” and seven didn’t vote. (The stated position of the United Methodist Church was against the amendment.)

And though the three largest Lutheran denominations in the United States opposed the prayer amendment, eight of the eleven Lutheran representatives voted for it (one didn’t vote). The Episcopal Church Executive Council opposed the amendment, but twenty-five of the forty-nine Episcopal representatives voted in favor of it, with three not voting. Similar relationships held for the Presbyterians (45 yes, 16 no, and 6 not voting), and for the Baptists (27 for, 10 against, and 5 not voting). Although a few Baptist bodies favored the amendment, the heads of the Southern and American Baptist Conventions publicly opposed it.

Roman Catholics, by far the largest religious grouping in the House, split 46 for, 48 against, and 6 not voting, though the U.S. Catholic Conference went on record opposing the prayer bill.

All four Friends representatives voted for the amendment, while the four congressmen listed as having “no religion” (see December 4, 1970, issue, page 33) all declined to vote in favor of it. Other breakdowns are listed in the accompanying chart (see next page). Jewish representatives overwhelmingly rejected the proposal, as did the Mormons, while those of the United Church of Christ, following the denomination’s lead, voted 7 yes, 12 no, with 2 not voting.

The two Evangelical Free Church members (the denomination belongs to the amendment-favoring NAE) split on the issue: powerful John B. Anderson (R.-Ill.) voted against, while Elford Cederberg voted for, the bill.

Representative Wylie, after the vote, said that now “everyone” will be waiting to see if what some opponents asserted is in fact true—that the First Amendment already solidly permits voluntary prayer in public buildings. If, he added, court rulings continue to assert that “no practice which smacks of being a prayer is permitted in public school buildings, then we will be back, because the American people will demand that we come back.”

High School Scene: What Prayer Amendment?

It was business as usual for Christians on high-school campuses across the nation before and after the congressional rejection of the prayer amendment (see preceding story). Students conducted Bible studies and prayer meetings on campus, invited Jesus-movement leaders and music groups to hold forth in assemblies, passed out Jesus newspapers, and even held revival services in cafeterias, schoolyards, and gyms. For many of the young activists, all the fuss about the amendment issue was yawningly irrelevant.

The spiritual awakening that has engulfed tens of thousands of older young people in the past few years is now at high tide in countless high schools. Established organizations such as Youth for Christ and Young Life2Youth for Christ has 850 campus workers and sponsors Campus Life clubs in 17,000 schools. Young Life has 200 staffers and 600 clubs reaching more than 60,000 youths. Both groups also rely heavily on thousands of volunteer workers. are a part of what’s happening, but the movement’s spread has been largely spontaneous and student-led.

Three youths at the Barboursville, West Virginia, high school began meeting daily for prayer, were joined by others, then finally were forced to move to the auditorium when more than 500 of the school’s 1,300 students packed in along with principal James Cain and several teachers. A number of students reportedly prayed to receive Christ during the meetings. Recently evangelist Bob Harrington (see August 30, 1968, issue, page 42) spoke at a voluntary-attendance assembly program. Cain says only ten students failed to come.

In January, Cherry Hill, New Jersey, senior Bob Patterson and several classmates began publishing the Ichthus, an underground-type newspaper. Their first press run consisted of 1,000 mimeographed copies beaming the Gospel to the 3,000 at Cherry Hill West. Demand and circulation rose monthly, and Ichthus became an eight-page tabloid by June, with a 26,000 circulation blanketing area high schools. This month Patterson, now a freshman at Philadelphia College of Bible, will increase this term’s circulation from 75,000 to 100,000—“and even higher if we can raise the money,” he says. The paper has made Jesus a big issue in classes, he says. A Jewish Defense League chapter moved to halt Ichthus distribution at Cherry Hill East high school, apparently making the paper more popular than ever.

Student evangelists have been hassled elsewhere, too. When 250 newly turned-on-to-Jesus youths created a revival atmosphere at Kailua (Hawaii) High School, the American Civil Liberties Union objected. Remarked one student bitterly: “Nobody complained when we were on drugs. Jesus has gotten us off drugs, and now they don’t want us to talk about him.”

In Seattle, a Unitarian minister lashed out at the heavy Jesus scene in high schools there. (After testimonies and songs by young Christian musicians in an assembly, students at one school voted to shut down classes and rap about Christ. About sixty students knelt in the halls and prayed to receive Christ, according to a teacher. The same music group—the New Men—has sung in hundreds of assemblies, with similar results at several other schools. Many Seattle-area schools have thriving student-led Bible study groups on campus.)

Christian students use many tactics to get their message across: term papers on the Jesus movement (often sparking classroom discussion), book reports on Christianity, dropping pointed questions, inviting evangelicals to participate in panel discussions on religion, and articles in school newspapers.

“How come all of a sudden people are turning on to a man that lived some two thousand years ago?” asked reporter Vickie Moyer in a feature in the Rosemead, California, high school paper. “Today in our lives we definitely need purpose, peace of mind, and most important of all, love and understanding between one another. Is Jesus Christ, who is becoming more alive to more and more people, the answer to our needs?”

Youth director James Ramsey of the 700-member Bethany Assembly of God church in Alhambra, California, beams a ministry to nine schools, including a Catholic girls’ school. His fourteen campus directors, collegians earning $10 a month, assist Bible study groups on all the campuses. Ramsey himself looks after five groups at the 2,500-member Alhambra high school. He and his staffers operate a five-hour dinner, training, and rally program at The Way Inn, a church facility, on Tuesday nights for the students from all nine campuses. They have staged Show Me, a contemporary Christian musical by Jimmy Owens, in several school assemblies. At an Arcadia high school assembly they featured baseballer Albie Pearson who gave his testimony—and an invitation to receive Christ. The assembly concluded outdoors with more than forty professing Christ. Reporter Harold Britton of nearby Mark Keppel high school wrote that groups held outdoor services at lunch hour, and that “the humanities and senior composition classes have spent most of their time talking about Jesus.”

Some students have been tossed out of school for their witness activities and told they could return only if they refrained from speaking up. Few, if any, have capitulated, and authorities have usually upheld the right of free speech on campus.

Debbie Parks, 14, was reinstated when her father, Spokane Jesus-movement leader Carl Parks (see January 29 issue, page 34), got firm with the principal. He used similar tactics in support of other young people witnessing and holding Bible studies on campus: “If you abuse our rights, we will sue.”

EDWARD E. PLOWMAN

Kenya’S ‘Madaraka Day’: Passing The Baton

“Madaraka Day” for the church, the Africans called the meeting. Madaraka is a Swahili word meaning “responsibility”; the same term was used by Kenyans when they received full independence from Britain in 1963.

But faith missions made history on October 16 in Machakos, Kenya, when the African Inland Mission (AIM) handed over to its offspring, the Africa Inland Church (AIC), all church and mission department leadership and ownership. About 20,000 people came from throughout the area for the meeting at the AIM’s Machakos station, founded in 1896. (Actual autonomy of the AIC dates to 1933, when the offspring national church took its name from the parent AIM.)

The Machakos meeting was important because it went far beyond implementing church autonomy. Noted AIM associate home director John Gration: “The Africans have had autonomy of their own church for some time; now they are actually being given autonomy of the mission in all its phases in Kenya.” And one missionary joked: “AIC now means ‘Africans in Charge.’ ”

Other faith missions have set plans in motion for such a handing over, but AIM Kenya was the first to implement it on a large scale.

The scope of the new mission-church relationship is very broad: AIM has forty stations and 260 missionaries in Kenya (it also works in Tanzania, Uganda, Zaïre, and the Central African Republic; the total missionary staff is almost 700). But the larger numbers come from the African church: 250,000 baptized members in 1,400 congregations in the AIC in Kenya, making it the largest church in that country and one of the largest in all Africa.

African church leaders and missionaries had met for several years engineering the takeover. Several factors led up to the almost inevitable event: nationalism (how could a church existing in a country now completely independent of colonial domination continue to be under the leadership of foreign missionaries?); pressure from the ecumenical crowd (the large Church of England, for example, is no longer called “The Church Mission Society,” the mission-field designation of the Anglicans—it is now the Anglican Church of Kenya); and the passage of time, which caused Africans and the missionaries to be receptive to greater responsibility by the national church.

The Machakos meeting showed a spirit of harmony and thankfulness. From top to bottom ranks, the Kenyans agreed that the meeting “does not signal that you missionaries are no longer wanted. We need you. And many of the departments that you have handed us, we give right back to you until we can run them with as qualified people as you are.” Missionaries were grateful for this attitude; they shuddered over the chaos caused by some denominational groups in other situations when they handed over leadership and property and then evacuated.

As the four-hour meeting ended with thousands of Africans and several hundred missionaries heading for home, a missionary was asked if things would be greatly changed by the action. “Not really,” he replied matter-of-factly. “This just makes things official.”

Meanwhile, mission societies similar to the AIM were watching and looking for guidelines from the Machakos meeting. Many of them doubtless will follow the AIM’s lead. The historic meeting seemed to indicate that such a handing over is in the best interest of all only when the program of world missions takes on the new concept of international church extension—for independents and faith groups, as well as for denominations. The 1970s will be the decade for “passing on the baton”—the time for “Paul to hand over to Timothy.”

HAROLD C. OLSEN

Libertyville For Lutherans

A new church was born in Libertyville, Illinois, last month. Signing on as charter members of the very conservative Federation for Authentic Lutheranism were six former Missouri Synod congregations and one independent group that split off from a Missouri Synod church that remained in the Synod.3St. John’s, Watertown, and Holy Trinity, Okauchee, both in Wisconsin; St. John’s of Libertyville, and St. Paul’s of Round Lake, both in Illinois; St. Paul’s First of North Hollywood, Grace of Bishop, and St. Paul’s of Escondido, all in California.

The new church body, conceived out of protest to alleged liberalism in the Missouri Synod and born out of opposition to developments at the Missouri Synod’s biennial convention in Milwaukee last July (see August 6 issue, page 31), claims a total of 8,000 baptized members. In addition, about fifteen pastors and laymen joined as advisory members without voting privileges.

By a vote of 19 to 0, delegates to the constituting convention approved a constitution that declares loyalty to the Bible as “the inerrant word of God.” Position papers adopted oppose the ordination of women ministers and hold that, while individual Christians have a responsibility to work for the betterment of society, “we are a Bible teaching church, leaving politics to the politicians and social advancement to the proper agencies.”

The FAL approved pulpit and altar fellowship with the 381,000-member Wisconsin Evangelical Lutheran Synod and the 15,000-member Evangelical Lutheran Synod. (The Missouri Synod has 2.8 million members in some 6,000 congregations.) FAL leaders said about fifty major congregations of the Missouri Synod will eventually join the new federation.

Bishops Open Meetings, Close Pulpits

During the first several days of the annual meeting of the U. S. Catholic bishops in Washington, D. C., last month, they (1) called for federal tax credits to aid parish schools, while slapping at recent Supreme Court decisions as denying “the fundamental right of parents to educate their children in non-public schools”; (2) voted against asking the Vatican even to restudy an ecumenical directive with a view toward simplifying pulpit exchanges between Catholic priests and Protestant ministers; and (3) voted to open many of their business meetings to the press and qualified observers beginning next April.

The tax-credit plan, designed to bolster the sagging financial underpinning for shrinking Catholic schools, would steer around direct state tax subsidies granted to parochial schools for the teaching of non-religious subjects. Instead, a parent could deduct from his federal tax payment half of a pupil’s expenses for textbooks and tuition. The bishops favored that plan over a tuition voucher because tax credits apparently avoid the problem of racial segregation and cover public as well as non-public schools. Parents—not schools—get the money. (Earlier this year the Supreme Court ruled against the constitutionality of direct state tax aid to church schools in Pennsylvania and Rhode Island.)

In a 181 to 81 vote, the prelates handily defeated a recommendation that might have allowed Catholic priests to preach in Protestant pulpits without special dispensation. Auxiliary John J. Boardman of Brooklyn argued that it would foster reciprocity and allow “heretics preaching in our pulpits.”

Countered Archbishop Philip Hannan of New Orleans: “It might make us more careful about what we preach.”

The U. S. hierarchy elected John Cardinal Krol, 61, of Philadelphia, a conservative, to succeed John Cardinal Dearden of Detroit as their president. Dearden, known as a moderate able to bring cohesion to the often-divided National Conference of Bishops, served five years and was ineligible. Krol was the NCCB vice-president, is an able administrator, and is a recognized leader. Whether his assertive style will polarize the bishops as some predict, remains to be seen.

RUSSELL CHANDLER