The CHRISTIANITY TODAY—Gallup Poll identifies who they are and what they believe.

Nearly a generation ago Henry Pitt Van Dusen predicted that the last half of the twentieth century would be remembered in church history as the age of Pentecostal charismatic Christianity. A few weeks ago a learned church watcher and personal friend of mine stated: “The Pentecostal-charismatic movement has passed its peak and is clearly on the wane.”

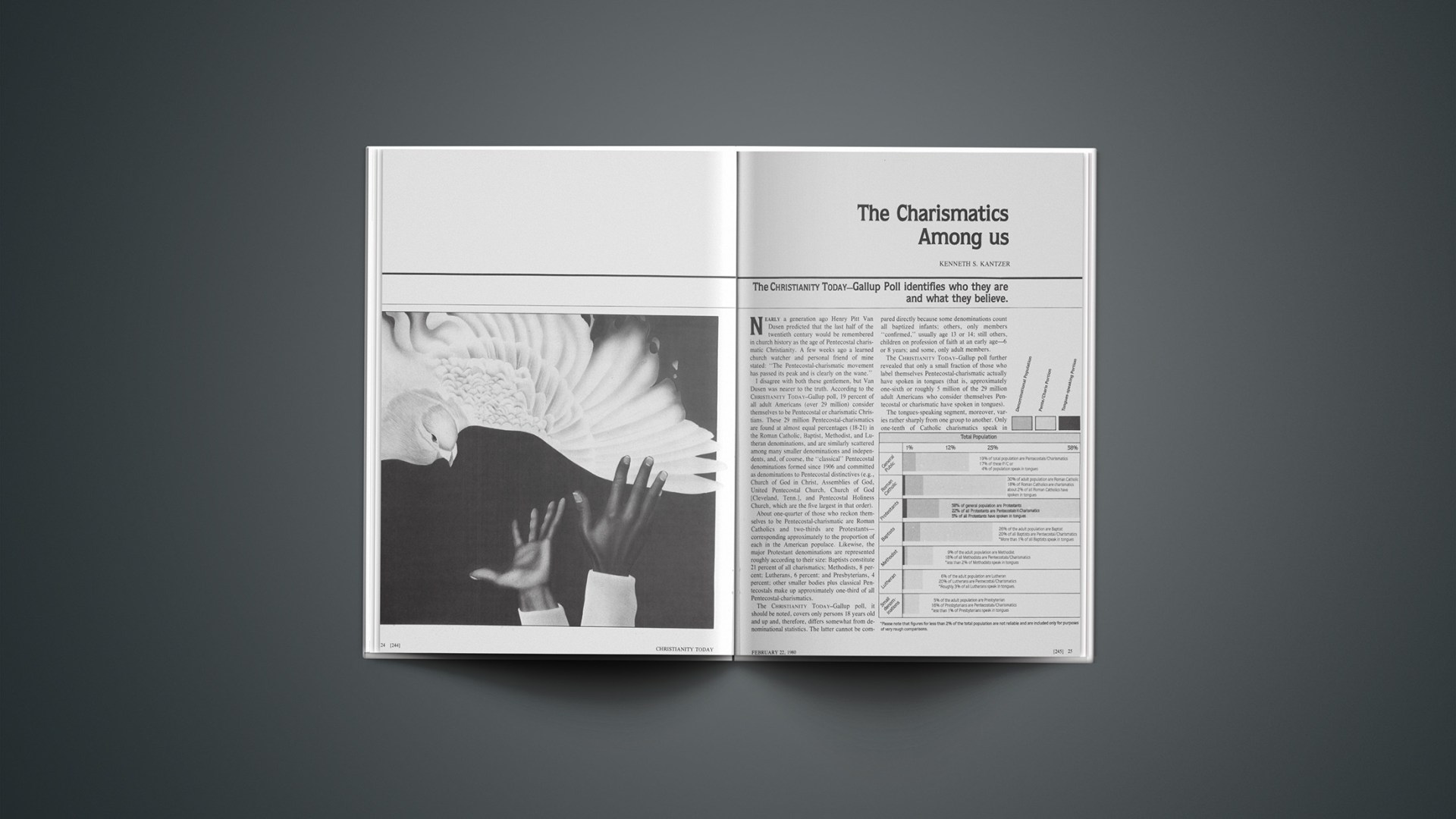

I disagree with both these gentlemen, but Van Dusen was nearer to the truth. According to the CHRISTIANITY TODAY-Gallup poll, 19 percent of all adult Americans (over 29 million) consider themselves to be Pentecostal or charismatic Christians. These 29 million Pentecostal-charismatics are found at almost equal percentages (18–21) in the Roman Catholic, Baptist, Methodist, and Lutheran denominations, and are similarly scattered among many smaller denominations and independents, and, of course, the “classical” Pentecostal denominations formed since 1906 and committed as denominations to Pentecostal distinctives (e.g., Church of God in Christ, Assemblies of God, United Pentecostal Church, Church of God [Cleveland, Tenn.], and Pentecostal Holiness Church, which are the five largest in that order).

About one-quarter of those who reckon themselves to be Pentecostal-charismatic are Roman Catholics and two-thirds are Protestants—corresponding approximately to the proportion of each in the American populace. Likewise, the major Protestant denominations are represented roughly according to their size: Baptists constitute 21 percent of all charismatics; Methodists, 8 percent; Lutherans, 6 percent; and Presbyterians, 4 percent; other smaller bodies plus classical Pentecostals make up approximately one-third of all Pentecostal-charismatics.

The CHRISTIANITY TODAY-Gallup poll, it should be noted, covers only persons 18 years old and up and, therefore, differs somewhat from denominational statistics. The latter cannot be compared directly because some denominations count all baptized infants; others, only members “confirmed,” usually age 13 or 14; still others, children on profession of faith at an early age—6 or 8 years; and some, only adult members.

The CHRISTIANITY TODAY-Gallup poll further revealed that only a small fraction of those who label themselves Pentecostal-charismatic actually have spoken in tongues (that is, approximately one-sixth or roughly 5 million of the 29 million adult Americans who consider themselves Pentecostal or charismatic have spoken in tongues).

The tongues-speaking segment, moreover, varies rather sharply from one group to another. Only one-tenth of Catholic charismatics speak in tongues (not one-tenth of all Catholics but one-tenth of the 18 percent of those Catholics who claim to be charismatics). One-fifth of all Pentecostal-charismatic Protestants speak in tongues; one-seventh of charismatic Lutherans do so; one-tenth of the charismatic Methodists, one-sixteenth of the charismatic Baptists, and a negligible portion of charismatic Presbyterians speak in tongues.

Looking just at those Pentecostal-charismatics who have spoken in tongues, we discover that the overwhelming majority (86 percent) are Protestant and only 14 percent Catholic. Among the Protestant tongues-speakers, 9 percent are Baptist; 4 percent, Methodists; 4 percent, Lutheran; and less than 1 percent, Presbyterians. Most tongues speakers (69 percent) are scattered minutely throughout many denominations and especially are to be found in classical Pentecostal denominations and independents.

The CHRISTIANITY TODAY-Gallup poll sheds considerable light on how the American people use the terms Pentecostal and charismatic. Most church watchers, including Pentecostals, are surprised at the number who call themselves Pentecostal-charismatic and wonder precisely what those who label themselves so actually mean by the term. Vinson Synan of the Pentecostal Holiness Church, and noted historian of the Pentecostal movement, writes: “I am not only surprised, I am astounded!” In explanation, he points to “the explosive growth among black Pentecostals and Catholic charismatics” and suggests that there is a “huge pool of ‘prayer group’ charismatics outside the normal flow of church life and statistics.”

That only 17 percent of the Pentecostal-charismatics speak in tongues was less surprising to Pentecostal-charismatic leaders. Previous studies show that from 50 to 66 percent of classical Pentecostal church members who accept Pentecostal teachings and who are full members of a Pentecostal denomination that is committed to Pentecostal distinctives have never spoken in tongues.

William Bentley, pastor of United Pentecostal Council of Assemblies of God, notes that the terms “Pentecostal” and “charismatic,” especially the latter, are largely white in origin. Many black Pentecostals traditionally preferred the term sanctified.” Kilian McDonnell, a Roman Catholic, points out that “a greater sophistication in theological areas and, therefore, both an appreciation of tongues and a correct view of its small place in the Christian life” have led to “a new look at tongues.” This is true even among classical Pentecostal denominations in Chile, he adds, citing some Pentecostal denominations, only 49 percent of whose pastors speak in tongues. Undoubtedly it is also true, as Jack Cottrell, a noncharismatic theologian of the Church of Christ, suggests: “Many reckon themselves as Pentecostal because they were reared in a Pentecostal body or because their closest affiliation or sense of ‘kinship’ is to a charismatic body even though they are not currently involved.”

Since the Bible clearly teaches that the Holy Spirit gives one or more spiritual gifts to every single Christian (note, for example, 1 Cor. 12:5ff.), in a sense every instructed Christian could claim to be charismatic (the word means gifted, from the Greek word charismata, gifts). In contemporary English the word is sometimes used in a religious context to refer to those Christians in denominations holding that speaking in tongues and other supernatural gifts are normative for the church today (usually called “classical Pentecostals” or simply “Pentecostals”). The term “charismatic” (or less frequently, neo-Pentecostal), however, is often distinguished from “Pentecostal” by restricting its reference to those within more traditional denominations who exercise or value tongues and other extraordinary gifts as a normal part of contemporary Christian experience.

The key word in these definitions is “normal” or “normative” because many non-Pentecostal charismatics will agree that God may give these gifts today but insist only that such supernatural gifts as tongues are neither the sign of a higher level of Christian experience nor are they promised as part of the normal Christian experience.

With the lessening emphasis upon actual speaking in tongues in recent years, especially among Catholic charismatics, McDonnell notes that the term is often applied “to all who have experienced a spiritual renewal, attend prayer meetings, or engage in other religious activities under general supervision of those in the renewal movement.”

A comparison of Pentecostal-charismatics and tongues speakers with the general populace and with evangelicals (evangelicals were defined in the first article in this series, issue of Dec. 21, 1979) reveals that those who claim to be Pentecostals or charismatics, taken as a whole, are more like the general populace, but the tongues speakers are much more like the evangelicals. Moreover, the figures for the Pentecostal-charismatics include the tongues speakers. The resemblance between Pentecostal-charismatics and the general populace would be even more startling if only charismatics who do not speak in tongues were compared with the populace. A further breakdown indicates that when “orthodox evangelicals” differ from “conversionalist evangelicals” the tongues-speaking Pentecostal-charismatics are more likely to follow the conversionalists.

It is evident that tongues-speaking Pentecostal-charismatics not only represent a significant portion of the evangelicals (40 percent), but the table below indicates that as a body they are in remarkable agreement with evangelicals. Tongues speakers, like their fellow evangelicals, are approximately nine-tenths Protestant and one-tenth Catholic; they hold both to the deity of Christ and the full truthfulness of all that is taught in Scripture; their only hope for heaven is through personal faith in Jesus Christ, the Savior; they acknowledge the existence of a personal devil who influences human beings for evil; they give generously to religious causes (even significantly more than their fellow evangelicals); they read the Bible faithfully; they acknowledge it as the most important religious authority for their life, even placing it over direct religious guidance of the Holy Spirit, which is their second most important religious authority; they set high priority on winning others to Christ and witness to others about their faith; they are members of a church; they do volunteer work for their church. Like other evangelicals they disapprove of sexual relations before marriage, and they do not use alcoholic beverages. From almost every point of view, in doctrine and practice they are part of the warp and woof of evangelicalism.

On some few issues, nevertheless, tongues-speaking charismatics differ significantly from other evangelicals. In the Pentecostal-charismatic group as a whole, women and men are represented in almost the exact same proportion as in the general public, whereas 62 percent of the evangelicals are women and only 38 percent are men. Only 42 percent of tongues-speaking Pentecostal-charismatics are women, however. This may reflect the fact that some charismatics do not encourage women to take leadership roles in the church.

Some tongues-speaking Pentecostals also give a slightly lower priority to winning the world for Christ than do other evangelicals. Horace Ward, executive secretary of the Society for Pentecostal Studies, suggests that this may reflect the still higher emphasis among charismatics on participation in corporate worship and their ministry through spiritual gifts, body-life programs, and discipleship.

Interestingly, tongues speakers do far better than any other group in knowing that Jesus said “Ye must be born again” to Nicodemus—far higher even than the conversionalist evangelicals; and, conversely, they did little better than the general populace and much worse than either orthodox or conversionalist evangelicals in ability to recall five of the Ten Commandments.

In political affiliation, evangelicals, Pentecostal-charismatics as a whole, and tongues speakers all conform closely to the pattern of the general populace except that evangelicals are likely to have a slightly higher percentage of Republicans and fewer independents whereas tongues speakers have significantly fewer Democrats (36 percent vs. mid-40s percentages for all other groups) and a higher percentage of independents (10 percent higher than any of the others).

Demographically, Pentecostal-charismatics are found in the central city in the same proportion as evangelicals (29 percent) but the percentage of tongues speakers in the inner city is larger than for evangelicals (only 17 percent of all evangelicals but 35 percent of all tongues speakers). By contrast, Pentecostal-charismatics are more likely to be located in the suburbs than are tongues speakers, and both tongues speakers and the Pentecostal-charismatic group seem to fare better in the suburbs than do evangelicals, while the reverse holds for small towns and rural areas.

Warning: Because of the small figures involved, data regarding tongues speakers should be taken only as general indicators, not as precisely accurate percentages.

When queried as to their explanation for the amazing growth of Pentecostal-charismatics over the last decade or two, leaders of the movement noted “The effects of 25 years of Oral Roberts, Full Gospel Businessmen, the television ministries of CBN and PTL, and the evangelistic fervor of Pentecostal churches.” Even more leaders, however, pointed to the moral and religious decline in America. Cottrell (as an outsider) writes: “The charismatic movement can be seen as the attempt to fill an emotional, experiential vacuum left in American Christendom that has become more liberal and more rationalistic.” Catholic McDonnell adds: “Churches do not seem to be offering spiritual depth. People go where they can (1) be fed, and (2) find community. They find their spiritual center in prayer groups rather than in parish life, even if they do not quit the parish. People want to experience God, not simply to know he exists. Charismatics have been able to show that God is here, now, today, a person, loving, caring, judging—and that they know this through experience. Thomas Zimmerman, general superintendent of the Assemblies of God, puts it bluntly: “People no longer felt comfortable in their former church relationships.”

Many pointed out that evangelicals have responded to Pentecostal-charismatic distinctives more tardily than have their more liberal or sacramental counterparts in American Christianity. William Menzies, chairman of biblical studies at Evangel College, suggests: “It is in the larger church world, loosely defined as nonevangelical, that the greatest awareness of spiritual need exists today. Evangelical Christianity in the United States has been more sure of its theological convictions than has the larger church world. It is more difficult for people of strong convictions to change opinion.”

Rapid growth of Pentecostal-charismatics poses serious problems, and these have not gone unrecognized by charismatics themselves. Only 59 percent of the entire group hold clearly to an evangelical view of salvation; less than half accept a personal devil. Only half accept an inerrant Bible, and less than half the Bible’s supreme authority; many do not have a traditionally orthodox view of the person of Christ.

“The charismatic movement as a whole is doctrinally unpredictable, at times marked and marred by a Corinthian elitism,” laments Russell Spittler, Assembly of God minister and associate dean of Fuller Theological Seminary. But he also notes: “Moral convictions often lag behind religious conversion.” Zimmerman adds: “The fact that people did not immediately understand all doctrine and did not adopt a biblical lifestyle did not mean their experience was not genuine. Assuming the commitment of those people to be genuine, it is my opinion they will become orthodox evangelicals. God does not wait until people have a perfect understanding of theology before granting regeneration and other spiritual blessings. In my opinion, however, there would be something drastically wrong if these people did not eventually accept the total teaching of Scripture.” Horace Ward then suggests a remedy: “Pentecostals should feel compelled by the statistics to add further emphasis to theological and biblical teaching. If our experience is to be a stable and valid one, it must be firmly based in the biblical faith. We must show our people that the most valid, most reliable, and most objective religious authority is the inspired record. We must also demonstrate that the most dangerous form of worldliness is that which affects our values rather than our manners.”

What is the significance of this vast new spiritual force unleashed upon the American church? Even Pentecostal-charismatic leaders would disclaim any suggestion that the movement is without fault or that it is solidly rooted in biblical faith or even that all parts of it are essentially Christian. As Menzies admits: “The new charismatics are not buying Pentecostal theology wholesale.”

To many, the Pentecostal-charismatic contribution to the church is a new awareness of gifts as ministry to the life of the church, new devotion techniques for public and private worship (not just tongues), the exercise of “body life,” an emphasis upon discipleship, and a means of penetrating the sacramental churches with Spirit vitality. Menzies says, “Denominational distinctions, sociological categorizations, political affiliations do not seem to follow sharp patterns where the Holy Spirit is welcomed … God’s spirit is breaking across boundaries that we did not know how to cross.” Zimmerman adds that the Pentecostal revival has brought an “evangelistic and missionary zeal that will hopefully challenge American Christians to greater efforts of bringing the gospel to the unsaved.”

Bentley perceives a subtle movement, unconscious perhaps, towards a “working ecumenicity.” He expects significant leadership for the churches as a whole springing from this group. He notes also that “Black Pentecostals, especially with their fairly unique contribution of theological conservatism and political-social radicalism, will provide a contribution of their own that will both challenge and contribute to the development of evangelicalism.”

The charismatic contribution, insists Kilian McDonnell, is “not an overblown doctrine of the Spirit, but a pneumatology that penetrates all theological concerns. The mutuality which exists between Christology and pneumatology will be recognized: there is no Christological statement which does not have its pneumatological counterpart.”

It is clear that Pentecostalism has traveled a great distance on the American scene in the last half-century, and most of that advance has occurred in the last two decades. In the eyes of Pentecostal-charismatics themselves this amazing penetration of American religion, so threatening to those in the more traditional churches, has first of all brought spiritual renewal and life to millions in the dead churches of twentieth-century America. “It is now fashionable,” William Menzies reminds us, “to make room for operations of the Holy Spirit.”

The CHRISTIANITY TODAY-Gallup poll documents what historians and sociologists and church workers in general have been telling us. As Kilian McDonnell says, “Charismatic renewal … is part of the religious life of American Christians. It is not going to go away, but it is and will remain a normal experience of the Christian life.”

But as the Belgian prelate Cardinal Leo Josef Suenens has said, to be most useful, the charismatic movement must disappear into the life of the church. It might even aid in the renewal of the Pentecostal churches.

Carl F. H. Henry, first editor of Christianity Today, is lecturer at large for World Vision International. An author of many books, he lives in Arlington, Virginia.