Elton Trueblood’s contributions intersect life at many different levels.

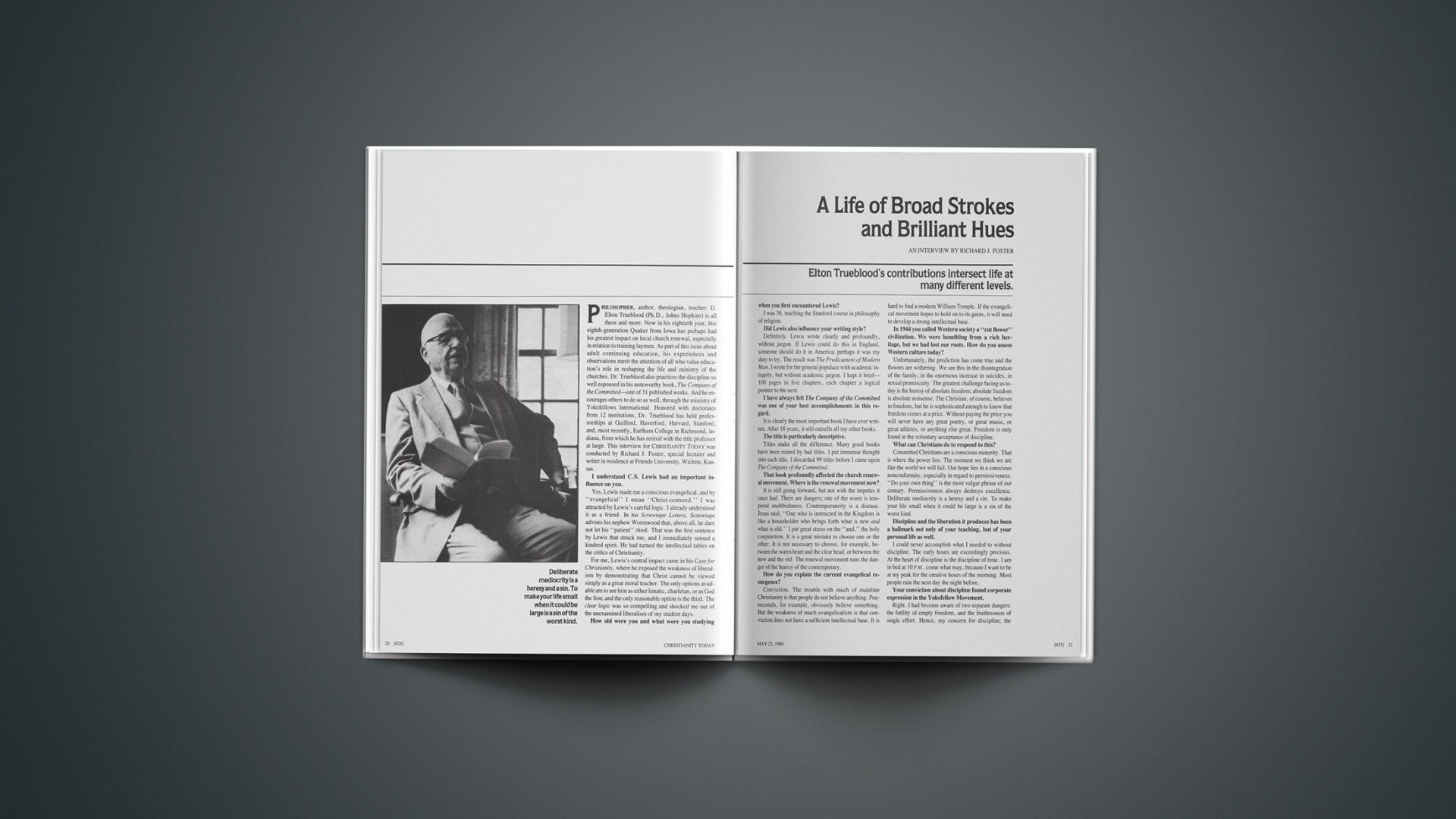

Philosopher, author, theologian, teacher: D. Elton Trueblood (Ph.D., Johns Hopkins) is all these and more. Now in his eightieth year, this eighth-generation Quaker from Iowa has perhaps had his greatest impact on local church renewal, especially in relation to training laymen. As part of this issue about adult continuing education, his experiences and observations merit the attention of all who value education’s role in reshaping the life and ministry of the churches. Dr. Trueblood also practices the discipline so well espoused in his noteworthy book, The Company of the Committed—one of 31 published works. And he encourages others to do so as well, through the ministry of Yokefellows International. Honored with doctorates from 12 institutions, Dr. Trueblood has held professorships at Guilford, Haverford, Harvard, Stanford, and, most recently, Earlham College in Richmond, Indiana, from which he has retired with the title professor at large. This interview for CHRISTIANITY TODAY was conducted by Richard J. Foster, special lecturer and writer in residence at Friends University, Wichita, Kansas.

I understand C.S. Lewis had an important influence on you.

Yes, Lewis made me a conscious evangelical, and by “evangelical” I mean “Christ-centered.” I was attracted by Lewis’s careful logic. I already understood it as a friend. In his Screwtape Letters, Screwtape advises his nephew Wormwood that, above all, he dare not let his “patient” think. That was the first sentence by Lewis that struck me, and I immediately sensed a kindred spirit. He had turned the intellectual tables on the critics of Christianity.

For me, Lewis’s central impact came in his Case for Christianity, where he exposed the weakness of liberalism by demonstrating that Christ cannot be viewed simply as a great moral teacher. The only options available are to see him as either lunatic, charletan, or as God the Son; and the only reasonable option is the third. The clear logic was so compelling and shocked me out of the unexamined liberalism of my student days.

How old were you and what were you studying when you first encountered Lewis?

I was 36, teaching the Stanford course in philosophy of religion.

Did Lewis also influence your writing style?

Definitely. Lewis wrote clearly and profoundly, without jargon. If Lewis could do this in England, someone should do it in America; perhaps it was my duty to try. The result was The Predicament of Modern Man. I wrote for the general populace with academic integrity, but without academic jargon. I kept it brief—100 pages in five chapters, each chapter a logical pointer to the next.

I have always felt The Company of the Committed was one of your best accomplishments in this regard.

It is clearly the most important book I have ever written. After 18 years, it still outsells all my other books.

The title is particularly descriptive.

Titles make all the difference. Many good books have been ruined by bad titles. I put immense thought into each title. I discarded 99 titles before I came upon The Company of the Committed.

That book profoundly affected the church renewal movement. Where is the renewal movement now?

It is still going forward, but not with the impetus it once had. There are dangers; one of the worst is temporal snobbishness. Contemporaneity is a disease. Jesus said, “One who is instructed in the Kingdom is like a householder who brings forth what is new and what is old.” I put great stress on the “and,” the holy conjunction. It is a great mistake to choose one or the other. It is not necessary to choose, for example, between the warm heart and the clear head, or between the new and the old. The renewal movement runs the danger of the heresy of the contemporary.

How do you explain the current evangelical resurgence?

Conviction. The trouble with much of mainline Christianity is that people do not believe anything. Pentecostals, for example, obviously believe something. But the weakness of much evangelicalism is that conviction does not have a sufficient intellectual base. It is hard to find a modern William Temple. If the evangelical movement hopes to hold on to its gains, it will need to develop a strong intellectual base.

In 1944 you called Western society a “cut flower” civilization. We were benefiting from a rich heritage, but we had lost our roots. How do you assess Western culture today?

Unfortunately, the prediction has come true and the flowers are withering. We see this in the disintegration of the family, in the enormous increase in suicides, in sexual promiscuity. The greatest challenge facing us today is the heresy of absolute freedom; absolute freedom is absolute nonsense. The Christian, of course, believes in freedom, but he is sophisticated enough to know that freedom comes at a price. Without paying the price you will never have any great poetry, or great music, or great athletes, or anything else great. Freedom is only found in the voluntary acceptance of discipline.

What can Christians do to respond to this?

Committed Christians are a conscious minority. That is where the power lies. The moment we think we are like the world we will fail. Our hope lies in a conscious nonconformity, especially in regard to permissiveness. “Do your own thing” is the most vulgar phrase of our century. Permissiveness always destroys excellence. Deliberate mediocrity is a heresy and a sin. To make your life small when it could be large is a sin of the worst kind.

Discipline and the liberation it produces has been a hallmark not only of your teaching, but of your personal life as well.

I could never accomplish what I needed to without discipline. The early hours are exceedingly precious. At the heart of discipline is the discipline of time. I am in bed at 10 P.M., come what may, because I want to be at my peak for the creative hours of the morning. Most people ruin the next day the night before.

Your conviction about discipline found corporate expression in the Yokefellow Movement.

Right. I had become aware of two separate dangers: the futility of empty freedom, and the fruitlessness of single effort. Hence, my concern for discipline; the small fellowship emerged. For years I had been impressed with the powers of Christian orders. They were strong precisely because of their corporate discipline. Hope lay in the creation of orders, and for a quarter of a century now, much of my thought and energy have gone into the Order of the Yoke. We engage in daily prayer, daily Scripture reading, weekly worship, proportionate giving, and study.

Study is among the first disciplines in the Yokefellow Movement. You have always stressed the importance of educating and equipping the laity for the work of the ministry.

Education is too good to limit to the young. The ministry of the laity is a great idea, but there is no magic in it. Unless the layman is given solid teaching, his ministry, after an initial burst of freshness, will tend to degenerate into little more than a string of trite phrases linked to commonplace ideas and buttressed by a few sloppily quoted biblical passages. We must take the education of the laity with utter seriousness. Lay persons are not assistants to the pastor, to help him do his work. Rather, the pastor is to be their assistant; he is to help equip them for the ministry to which God has called them. The difference is as revolutionary as it is total. Half measures are worse than nothing. Our hope lies in making big plans, in undertaking to produce a radical change, in aiming high. Adult education is the big thing in the church. It is not a decoration, it is the centerpiece.

What curriculum do you envision?

A five-year course that can be taught by pastors. The first year, the Hebrew prophets. Make use of the best commentaries and the insights of modern scholarship for depth and interest. The second year, the Synoptic Gospels. Students can develop their own harmony of the Gospels, and thus wrestle with the issues. The third year, the Christian classics. The average Christian is abysmally ignorant of the wealth of devotional literature from the past: Augustine’s Confessions or Pascal’s Pensées, for example. The fourth year, the intellectual understanding of the Christian faith. This gives an opportunity to work out a reasoned belief, and to struggle with the hard problems of theology and philosophy. There is no good reason why knowledge of Christian apologetics must be confined to the seminary trained. The fifth year, the history of Christian thought. The rise and decline of various heresies, the growth of the papacy, the beginnings and completion of the Reformation, the origin of contemporary denominations, the conflict with science—all these and many more topics can fill a gap in the knowledge of many Christians.

Are curriculum materials available, or do pastors start from scratch?

The curriculum is available at The Yokefellow Academy.

Central to this emphasis is the concept of the equipping ministry. Has this concept been generally accepted?

The equipping ministry has only partly taken hold. In many seminaries they have not heard of the concept. They still equate pastor and minister, which is a horrible mistake. Some pastors reject the concept. One pastor said to me, “This is my one chance for prestige and separation from the common man, and I’m not going to give it up.” Do you see what that does to the idea of the pastor as an equipper, as a servant? It destroys it entirely. But I am glad for the many places where people have put the idea into practice and new life is blossoming.

You say equating “pastor” and “minister” is a mistake. What’s the difference?

A pastor is a professional. Every Christian is called to minister.

There is much concern about the future of the Christian college. Several are facing financial crises and others have an identity crisis. What is your assessment?

When the Christian college emerged, it appeared as a genuine novelty. Curiously, it appeared in its fullness only in the United States. What developed in America was not so much education in specifically Christian subjects as education in all subjects from a Christian perspective. The idea is a great and worthy vision, but the sad and uncontested fact is that the vision has dimmed. However great the financial problems are, they are not the major problem. The major problem is a loss of meaning and identity. If the Christian college ceases to be consciously committed to the Christian revelation, it has nothing to give. Under those circumstances I’d much rather go to Purdue—there would be far better facilities and a far better football team! When the Christian college loses its Christian commitment it becomes a poor little thing, a glorification of mediocrity. Whether we can recover the roots, I do not know, but unless we do the case is lost.

What new directions do you see in philosophy?

The great new development will be a better epistemology. The shame has been that in the recent past, so much of our philosophy has been mere word mongering that doesn’t affect life at all. It has been far from the spirit of Socrates. But that day is passing; we are seeing both a new concern for knowledge and a new humility in the epistemological task. Of all people, Christians should have a keen interest in epistemology, because an unexamined faith cannot be sustained.

In your autobiography you speak of the importance of living life in chapters. What chapter do you see yourself in now?

This chapter is one of encouragement. I want to give the rest of my life to encouraging young authors. I am not going to write anymore—that is a firm decision. I’m letting some collections be made of former publications, but I want to give my prime energies to urging others to take up the task.

Carl F. H. Henry, first editor of Christianity Today, is lecturer at large for World Vision International. An author of many books, he lives in Arlington, Virginia.